To borrow some words from Dickens:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

No doubt, this is very much how the current period feels for many of us. There are some fantastic things happening in local communities and in our sector, but for many of us it is also the worst of times. Some of us are away from home, or our usual support networks, our routine has been disrupted and there is a constant air of uncertainty.

Its ok, to not be ok. More now than ever. We are being asked to increasingly engaged with digital tools and media, some for the firat time, and this can have a massive impact on our wellbeing. So how do we support our wellbeing whilst adapting to new ways of learning and working?

Teaching Continuity

Guidance for staff

One of the recurring themes in the wellbeing literature across all student groups, K-12 and Higher Education, is the importance of being known by their teachers. Students who feel that their teachers know them and their capabilities are less anxious and perform better than those that do not. Being seen.

With many students distributed across the globe, how do we let them know that they are seen? Both in our support for them and in planning our teaching continuity activities.

It is hard to know where your students may and what technologies they will have access to. They may have a laptop, but may also have limited access to a good internet connection. You also need to consider what additional needs your students may have, see our post on Accessibility and Teaching Continuity.

At the same time, you will be working from home, often not at a proper desk and may be looking after others in your household. It’s important to factor in and support your own wellbeing.

Some things to think about:

- Be kind. To yourselves and your students. Expect to be less productive, there’s a lot going on.

- What are the key things your students need to know – the key learning objectives and threshold concepts?

- What is the simplest way of enabling that learning to happen?

- Talk to Arena and Digital Education colleagues. Check what support is available via the Teaching Continuity pages.

- Video is great but its exhausting and requires good internet access.

- Does the session need to be live? Pre-record where you can, its both less stressful and exhausting.

- Keep videos short.

- Do you have students that need captions or transcripts?

- Can you provide the information in an alternative way e.g. a reading or set a research task.

- Show your students you care – send them an email, arrange virtual office hrs – doesn’t have to be video, could be an advanced forum or chat in Moodle.

- Don’t try to replicate everything online, it isn’t the same and shouldn’t be.

- Be clear with your expectations.

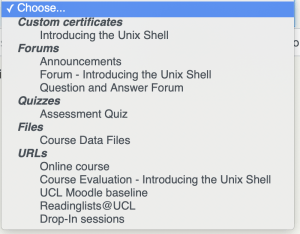

- Remove or hide any unneccessary content on your Moodle course. Some of your students will try do or read everything.

- Write yourself a schedule, include plenty of breaks and non-screen time.

- Talk to your colleagues – virtual coffee mornings or meetings, make use of the chat in MS Teams. Why not take part in an #LTHEChat or catch-up on previous chats?

Guidance for students

First, breathe. There’s a lot happening and a lot changing on a daily basis. We understand that you are doing your best in very difficult circumstances. Keep in contact with your friends and loved ones as much as possible, remember we are physically distancing.

We recommended that you regularly check the Contunuing to learn remotely guidance as it is being regularly updated. It provides some basic guidance around how to get started and learn effectively online as your tutors switch to teaching in a digital format.

The student mental health charity Student Minds have produced some additional coronavirus guidance on looking after your mental health.

Please also check the Support for Students FAQs on the UCL Advice for staff and students who may have concerns about the outbreak of coronavirus web page.

There is additional guidance and support available from Students’ Union UCL including FAQs.

Staff wellbeing

Working from home can be difficult. Whether you’re teaching, researching or in an academic-related role things can be difficult and at times isolating. It’s ok to be less productive than usual.

Firstly, check out the Support for Staff FAQs on the UCL Advice for staff and students who may have concerns about the outbreak of coronavirus web page. This is the key information hub.

Review the Remote working – tools and best practice guidance, this is generic guidance for all those working from home. In addition, UCL Workplace Wellbeing have produced some support resources. In addition, SLMS have collated some nice resources for coping with Working in a Crisis.

Childnet International have a range of guidance on digital wellbeing for children and young adults, including a Digital Wellbeing pack for parents. It is increasingly important that we are mindful of everyone’s digital wellbeing at this time. Especially as we are spending increasing amounts of time online. You may also want to review this Jisc blog post Looking after your own, and others’, digital wellbeing .

General guidance

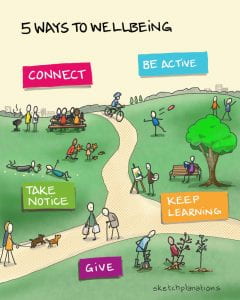

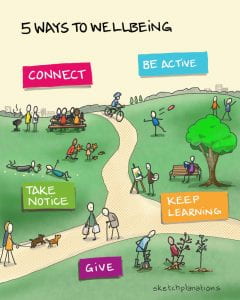

Taken from: https://whatworkswellbeing.org/about-wellbeing/how-to-improve-wellbeing/

At this time its important to remember that we are actually being asked to physically distance ourselves from colleagues and loved ones, not socially distance. Remain socially connected is essential to our wellbeing and will help reduce and sense of loneliness or isolation.

The first thing is to limit your exposure to the news. Only check the news once or twice a day for key updates, any more than this is unneccessary and may only increase any anxiety.

Secondly, take a break from your smart device. Put it in a box for an hour. Go do something else: read a book, do some colouring, if you have one go out into the garden. This will help reduce the sensory and cognitive overload.

Thirdly, if you are fit and healthy and its permitted, get outside. Exercise, even if it’s just a walk around the block can work wonders to enhance your mood.

Fourth, check out the Blurt foundation’s resources, inparticular the Coronavirus Helpful Hub.

Fifth, the NHS Every Mind Matters website now has 10 tips to help if you are worried about coronavirus.

UCL has published a range of guidance aimed at both staff and students to support you during this time:

References

- Dickens, C. (1859). A Tale Of Two Cities By Charles Dickens. With Illustrations By H. K. Browne. London: Chapman and Hall.

- “Not by degrees: Improving student mental health in the UK’s universities”. (2017), IPPR, 4 September, available at: https://ippr.org/research/publications/not-by-degrees (accessed 6 September 2017).

- O’keeffe, P. (2013), “A Sense of Belonging: Improving Student Retention”, College Student Journal, Vol. 47 No. 4, pp. 605–613.

- “PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students' Well-Being”. (2017), , Text, , available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/pisa-2015-results-volume-iii_9789264273856-en (accessed 13 November 2019).

- https://whatworkswellbeing.org/about-wellbeing/how-to-improve-wellbeing/

Close

Close