From Dr Jenny Bunn

In receipt of an E-Learning Development Grant, Jenny has created DiSARM: Digital Scenarios for Archives and Records Management. Her project aimed to develop a number of digital scenarios to enhance the e-learning opportunities for students on the Department of Information Studies’ (DIS) archives and records management programmes. Below is her report, as a guest blog post:

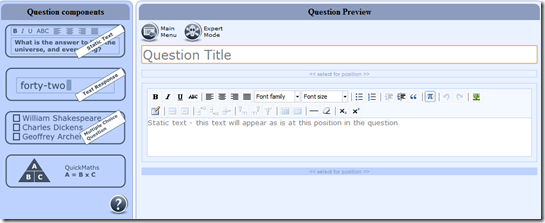

This post sets out a question that has arisen as the result of work within the Department of Information Studies to incorporate more e-learning tools and techniques within its teaching. Last year the department was fortunate enough to win an e-learning development grant to undertake a project entitled Digital Scenarios for Archives and Records Management (DiSARM). As the name suggests the project was focussed around the department’s archives and records management programmes and involved the development of scenarios which would enhance both the digital content and context of these programmes. Content, because it is increasingly important for our students to be familiar with a wide range of processes and products employed to ensure the preservation of born digital records, and context, because it is equally important that they should be exposed to methods of teaching and (e-)learning that will enable them to gain confidence and experience of working in an online and collaborative way as part of a global community.

It is not my intention to describe the project in detail here. Those who are interested in reading more may download the full report. Rather I wish to highlight a question that emerged from the project and which seems to encompass many of the issues raised by e-learning.

‘How far can institutions put a boundary around a learning experience?’

This question is raised, in this form, by Mayes and de Freitas (2007) who also comment that new technologies mean that ‘learning can be socially situated in a way never previously possible’. With the DiSARM project an issue arose in the form of the negotiation of the boundary between the safe controlled environment of UCL’s VLE Moodle and the wider community beyond. Digital preservation is still in an embryonic state so should the students’ messy and often unsuccessful experimentation with it be contained within the walls of the Moodle or out there on the internet for the benefit of the professional community at large?

This though would seem to be only one of the frames in which it is possible to see the question of a boundary around the learning experience. For example, it would also seem to encompass current debates about Open Educational Resources and increases in university fees, as well as old ones such as that of the relationship between theory and practice. Sadly I have no easy answers to offer, but one avenue that I think might be worth exploring is a way to combine ideas about ‘authenticity and presence’ (Land and Bayne 2006) with those about e-moderation. E-moderation is a subject of much debate (e.g. Salmon 2000) and there is some evidence (Hewings, Coffin & North 2006) of anxiety amongst teachers, in the context of new e-learning technologies, with regards to their ability to achieve the proper balance between not interfering too much so as to stifle learners learning, and yet not interfering too little so as to allow dominant voices to drown out weaker ones.

One hypothesis would be then that, what was previously a passive and unacknowledged ‘presence’ has now become an active process of, yes moderation, but perhaps something else as well? Perhaps the role of the teacher has always been to make learning visible, to provide the definition or boundary that allows students to see the ‘something’ they are learning, the frame against which to set and assess it?

References

Hewings, A., Coffin, C. & North, S. (2006) Supporting undergraduate students’ acquisition of academic argumentation strategies through computer conferencing, Higher Education Academy report. http://bit.ly/N2G2OU [Accessed June 2012]

Land, R. and Bayne, S. (2006) Issues in Cyberspace Education. In Savin-Baden, M. & Wilkie, K. (eds) (2006) Problem-based learning online Open University Press.

Mayes, Y. and de Freitas, S. (2007) Learning and e-learning: the role of theory. In Beetham, H. & Sharpe, R. (Eds) (2007) Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: designing and delivering e-learning London, Routledge.

Salmon, G. (2000) E-moderating: The Key to Teaching and Learning Online London, Kogan Page.

Close

Close