Chronogogy – Time-led learning design examples

By Matt Jenner, on 15 November 2013

I recently blogged about a concept called chronogogy; a time-led principle of learning design the importance of which I’m trying to fathom. My approach is to keep blogging about it & wait until someone picks me up on it. Worst case, I put some ideas out in the public domain with associated keywords etc. Please forgive me.

An example of chronogogically misinformed learning design

A blended learning programme makes good use of f2f seminars. Knowing the seminar takes at least an hour to get really interesting, the teacher prefers to use online discussion forums to seed the initial discussions and weed out any quick misgivings. Using a set reading list, before the seminar they have the intention of students to read before the session, be provoked to think about the topics raised and address preliminary points in an online discussion. The f2f seminars are on Tuesdays & student have week to go online and contribute. This schedule is repeated a few times during the twelve week module.

The problem is, only a handful of students ever post online and others complain that there’s “not enough time” to do the task each week. The teacher has considered making them fortnightly, but this isn’t really ideal either, as some may slip behind, especially when this exercise is repeated during the module.

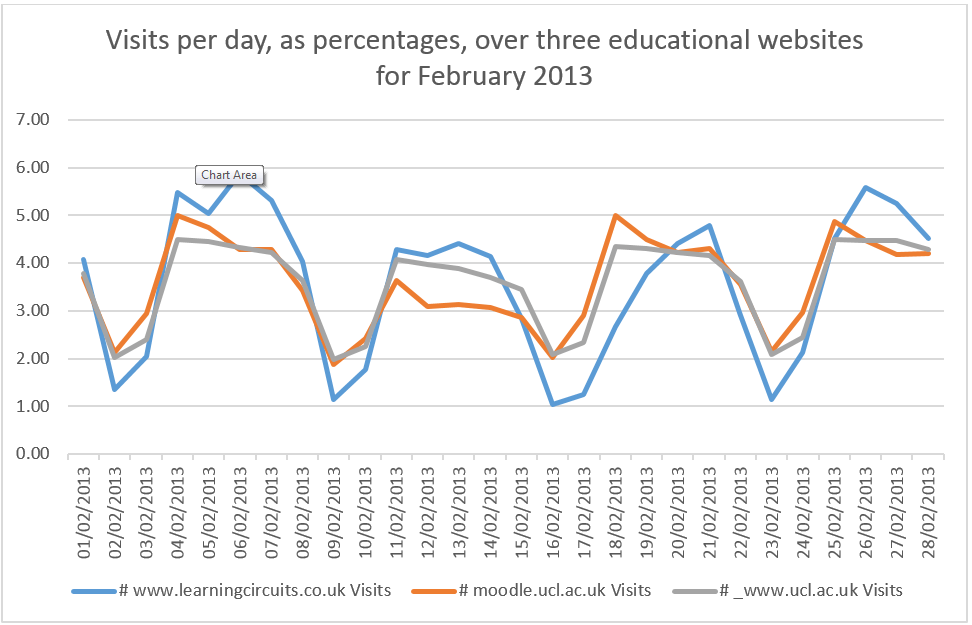

The argument in my previous post was that if the planning of the activity doesn’t correlate well with activity of website users then it may increase the chance of disengagement.

Example learner 1

|

|

Tues | Wed | Thurs | Fri | Sat | Sun | Mon | Tues |

|

Learner1 |

Task set | Reading start | Reading finish | Contributes to forum | Attends seminar |

If a reading is set on Tuesday completed by Sunday, the learner may only start considering their discussion points on Sunday or Monday night. This will complete the task before Tuesday’s session, but does it make good use of the task?

Example learner 2

|

|

Tues | Wed | Thurs | Fri | Sat | Sun | Mon | Tues |

|

Learner1 |

Task set | Reading start | Reading finish | Contributes to forum | Visitsforum | Contributes to forum | Attends seminar |

The reading is set on Tuesday, completed by Friday, the learner even posts to the forum on Saturday. By Sunday the come back to the forum, there’s not much there. They come back on Monday and can contribute towards Learner 1’s points, but it could be too late to really fire up a discussion. The seminar is the next day, Tuesday which could increase the chance of discussion points being saved for that instead, as the online discussion may not be worth adding to.

These are two simplistic example, but they provide further questions:

- Q: Can these two students ever have a valuable forum discussion?

- Q: Is this was scaled up would the night before the seminar provide enough time for a useful online discussion?

- Q: If Learner3 had read the material immediately and posted on the Wednesday what would’ve been the outcome?

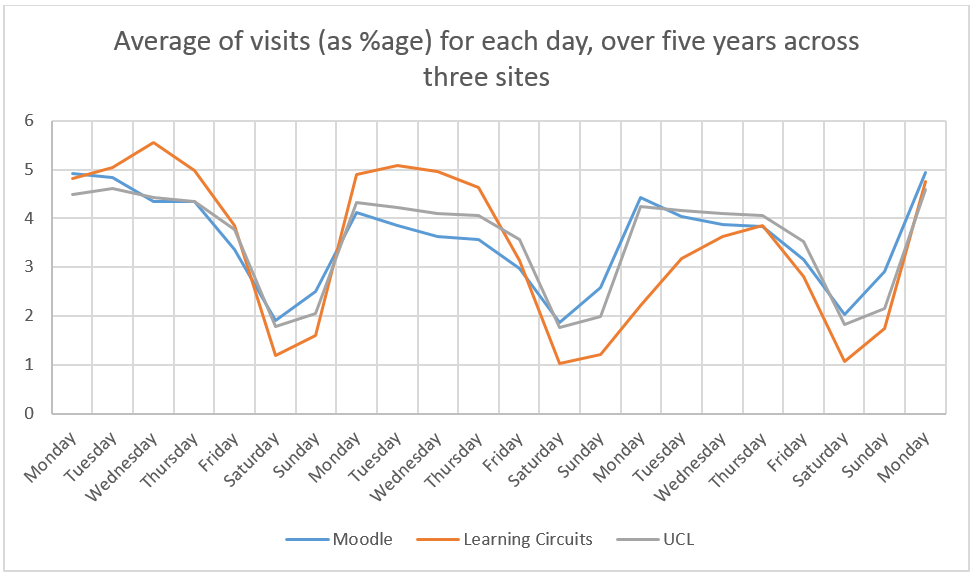

Any students posting earlier in the seven-day period may be faced with the silence of others still reading. Postings coming in too late may be marred by the signs that fewer visitors will log on during the weekend. Therefore, unless people are active immediately after the seminar (i.e. read and post in the first day or two) then any online discussions takes place on Monday – the day before the seminar.

In this example a lot of assumptions are made, obviously, but it could happen.

Development/expansion

If this example were true, and it helps if you can believe it is for a moment, then what steps could be taken to encourage the discussion to start earlier?

One thought could be to move the seminar to later in the week, say Thursday or Friday. By observing learners behaviour ‘out of class’ (offline and online) it could give insight into the planning of sessions and activities. In the classic school sense, students are given a piece of homework and they fit it in whenever suits them. However, if that work is collaborative, i.e. working in a group or contributing towards a shared discussions, then the timing of their activity needs to align with the group, and known timings that are most effective.

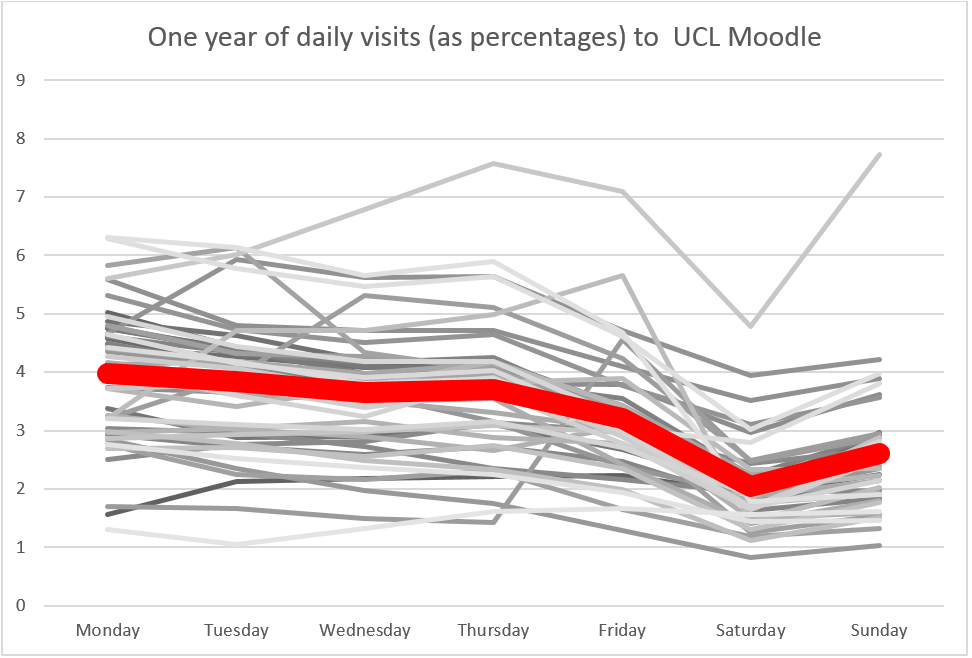

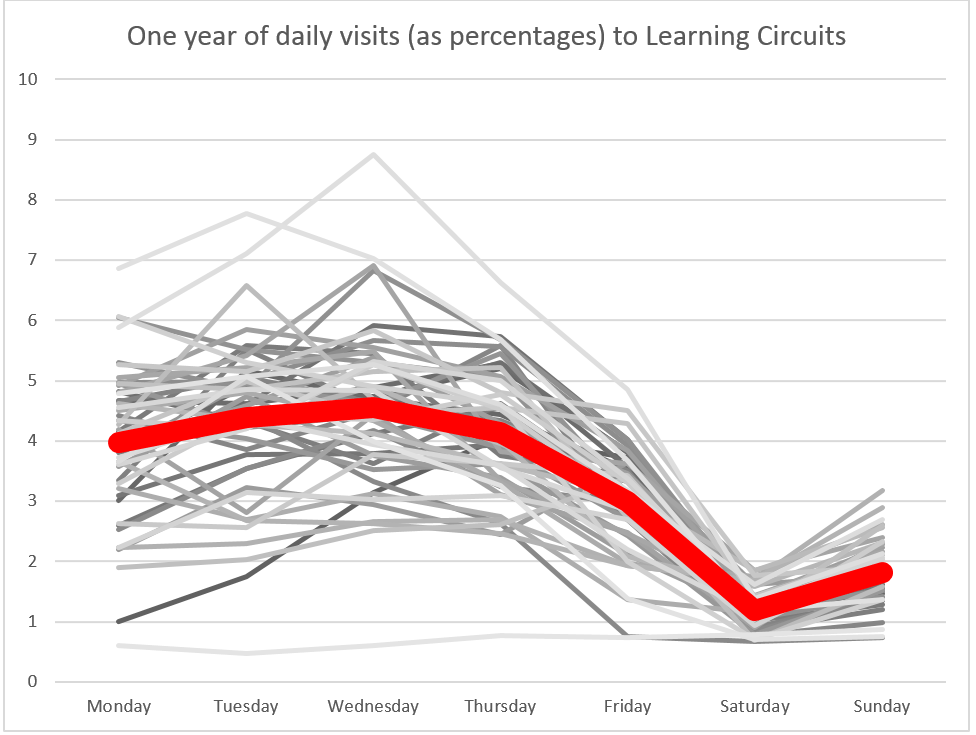

Time-informed planning

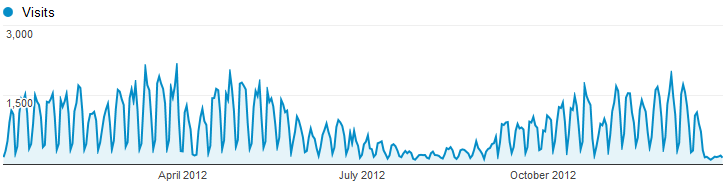

Knowing study habits, and preferences, for off and on-line study could make a difference here. If the teacher had given the students a different time over the week it might have altered contributions to the task. Data in the previous post indicates that learners access educational environments more in the week than the weekend. An activity given on Friday and expected for Monday seems unfair on two levels; a weekend is an important time for a break and weekends are not as busy as weekdays for online activity.

If the week shows a pattern of access for online, then an online task could be created around the understanding of access patterns. If online tasks are planned around this, then it may affect the outcome.

Does time-informed learning design make a difference?

There’s only one way to know, really, and that’s to perform an experiment around a hypothesis. The examples above were based on a group/cohort discussion & it made a lot of assumptions but it provides a basis of which I wanted to conduct some further research.

Time-based instruction and learning. Is activity design overlooked?

In the examples, the teacher is making an assumption that their students will ‘find the time’. This is perfectly acceptable, but students may better perform ‘time-finding’ when they are also wrapped into a strong schedule, or structure for their studies. Traditionally this is bound to the restrictions of the timetabling/room access, teacher’s duties and the learners’ schedules (plus any other factors). But with online learning (or blended) the timetabling or time-planning duty is displaced into a new environment. This online space is marketed as open, personalised, in-your-own-time – all of which is very positive. However, it’s also coming with the negative aspect of self-organisation and could, possible, be a little too loosely defined. Perhaps especially so when it’s no longer personal, but group or cohort based.

There’s no intention here of mandating when learners should be online – that’s certainly not the point. In the first instance it’s about being aware of when they might be online, and better planning around that. In this first instance, the intention is to see if this is even ‘a thing to factor in’.

Chronology is the study of time. Time online is a stranger concept than time in f2f. For face to face the timing of a session is roughly an hour, or two. Online it could be the same, but not in one chunk. Fragmentation, openness and flexibility are all key components – learners can come and go whenever they like, and our logs showing how many UK connections are made to UCL Moodle at 3-5AM show this quite clearly.

Chronogogy is just a little branding for the foundation of the idea that instructional design, i.e. the planning and building of activities for online learning, may need to factor time into the design process. This isn’t to say ‘time is important’ but that by understanding more about access patterns for users, especially (but not necessarily only) online educational environments, could influence the timing and design of timing for online activities. This impact could directly impact the student and teacher experiences. This naturally could come back into f2f sessions too, where the chronogogy has been considered to ensure that the blended components are properly supporting the rest of the course.

Time-led instructional design, or chronogogically informed learning design could potentially become ever more important if considering fully online courses that rely heavily on user to user-interaction as a foundation to the student experience. For example the Open University who rely heavily on discussion forums or MOOCs where learner to learner interaction is the only viable form.

Most online courses would state that student interaction is on the critical path to success. From credit-bearing courses to MOOCs – it’s likely that if adding chronogogy into the course structure, then consideration can inform design decisions early in the development process. This would be important when considering:

- Planned discussions

- Release of new materials

- Synchronous activities

- Engagement prompts*

In another example, MOOCs (in 2013) seem to attract a range of learners. Some are fully engaged, participate in all the activities, review all the resources and earn completion certificates. Others do less than this, lurking in the shadows as some may say, but remain to have a perfectly satisfactory experience. Research is being performed into these engagement patterns and much talk of increasing retention has sparked within educational and political circles, for MOOCs and Distance Learning engagement/attrition.

One factor to consider here is how you encourage activity in a large and disparate group. The fourth point above, engagement prompts, is a way of enticing learners back to the online environment. Something needs to bring them back and this may be something simple like an email from the course lead. Data may suggest that sending this on a Saturday could have a very different result than on a Tuesday.

Engagement prompts as the carrot, or stick?

Among many areas till to explore is that if learners were less active over the weekends, for example, then would promoting them to action – i.e. via an engagement prompt, provide a positive or negative return? This could be addressed via an experiment.

Concluding thoughts

I seem interested in this field, but I wonder of its true value. I’d be keen to hear you thoughts. Some things for me to consider are:

- If there’s peaks and troughs in access – what would happen if this could be levelled out?

- How could further research be conducted (live or archive data sets).

- Have I missed something in the theory of learning design that is based on time-led instruction?

- I wonder what learners would think of this, canvas for their opinions.

- Could I make a small modification to Moodle to record data to show engagement/forum posting to create a more focused data set?

- Am I mad?

Close

Close