Have you ever wondered what to make of an assertion about human ability to learn? That somebody has or hasn’t got a ‘maths brain’, for example, or that human ability to acquire a new language is limited by age? Research in neuroscience and psychology is growing fast – and yet when findings surface in the media, most educators outside those fields find it hard to judge their validity, make sense of them in relation to other often conflicting findings, or extrapolate from them into practice. Educators and educationalists are in need of a field dedicated to this task of synthesis. Thankfully such a field now exists and is known as Mind, Brain and Education Science.

Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa and Mind, Brain and Education Science

Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa

Mind, Brain and Education Science (MBE) has been gathering ground in recent years and has become an established course of study at several institutions across the world – at Harvard it is available as undergraduate module, Masters programme and doctoral concentration. The field has a dedicated journal, Mind, Brain and Education, and a professional body with the admittedly inauspicious name of IMBES.

Flipping as an inclusive practice

During her time at UCL Tracey carried out a number of engagements, including an Engineering Learning Lunch, a seminar with Brain Sciences, a visit to UCL’s academy, and a public lecture on MBE tenets across the human lifespan – but the focal point of her visit was a workshop titled ‘The Flipped Classroom’. Here Tracey brought her MBE disciplinary knowledge into play with the flipping initiative already underway at UCL, encouraging participants to examine the workings of flipping and make informed decisions about teaching.

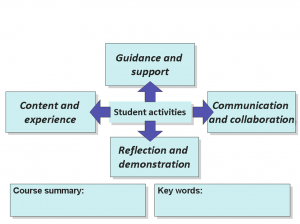

Over two days 16 participants familiarised ourselves with the most important principles of flipping, put them into practice, exchanged experiences, and considered each others’ work. The first section of the workshop was dedicated to principles of learning, drawing on MBE research and posed as a series of provoking questions. We discussed backwards design (which UK educationalists such as Biggs refer to as ‘constructive alignment’) of activities and assessment, always based on learning objectives which do not change. We then discussed the need for inclusive teaching practices which arises from these unchanging objectives, and how flipping can, if well-conceived, enable students with individual differences to reach the levels of knowledge they need to progress and succeed in that discipline. Based on MBE principles, we expect flipping to work in some key ways. Where flipping allows students the time to familiarise themselves with core concepts and pursue their own questions before the lecture (which we should perhaps start calling a ‘plenary’), they are more confident asking questions – as a learning activity, asking questions is more demanding than reproducing knowledge from memory because good questions depend on bringing prior knowledge into play and building from it. A flipped lecture can set out the boundaries of what is expected of a cohort at a certain level, and it can act as a reference.

You might ask, doesn’t this actually boil down to the age-old problem of student motivation to read their set texts? If students won’t do the work, then why should they expect to succeed? Tracey responds that teaching is best judged by the success of those students who are least likely to succeed, rather than most likely. Flipping doesn’t present itself as an alternative to the texts and so poses no obstacles to engaging with them; rather it exploits newly available verbal and non-verbal forms of academic communication, and recognises that many students experience particular barriers to ‘the work’ when ‘the work’ is reading. MBE science indicates that students benefit from signposts, encouragement and other ways in. Tracey discussed the expressive power of video (and I had a side discussion with my neighbour Anne about the Gutenberg parenthesis) and its ability to engage by introducing change, texture and emphasis. She expanded on the MBE basis for variation in teaching: the human brain is alert for and pays particular attention to change. She acknowledged that many lecturers have taken measures to introduce the variety into their presentations and that recordings which don’t exploit that medium can be equally flat and homogenous – perhaps more so. Flipping isn’t a religion, she points out, but a tool.

You might also question the need for interactivity and participation during the lecture – isn’t it sometimes the case that students simply want to know what the academic knows? You might point out that the lecture itself is a way in, preparing students to contribute to their seminars or tutorials. Tracey emphasises that the person who does the work does the learning – in their prevailing form lectures make it easy for everybody to relax except for the sweating lecturer. Accordingly, the best flipping practices make students work hard. Another factor is contact time – it’s debatable whether an event at which people sit together in silence, watching and listening to a presentation in which they are unlikely to intervene, can accurately be called ‘contact’. This observation isn’t restricted to higher education – at a recent HEA event, Power in Your Pocket, Mary Oliver (Head of the Performance Research Centre at the University of Salford) introduced us to the work of Jacques Rancière. In his 2009 dialectic The Emancipated Spectator, Rancière advances a radical view of the theatre not as a site for spectacle, but for community participation. While I’m convinced that the vast majority of students and academics would (even if pragmatically) defend the current separation of academic and student role, I also think most would subscribe to this view of learning (p11):

‘The distance the ignoramus [Rancière’s term for somebody who knows little] has to cover is not the distance between her ignorance and the schoolmaster’s knowledge. It is simply the path from what she knows to what she does not yet know, but which she can learn just as she learnt the rest; which she can learn not to occupy the position of scholar, but so as better to practise the art of translating, of putting her experience into words and her words to the test; of translating her intellectual adventures for others and counter-translating the translations of their own adventures which they present to her.”

What is best to flip?

Since recording and uploading a lecture is different from flipping, we then tackled the question of what to flip – or to put it a better way “What is the best use of my face-to-face time with students?” Some activities such as practice, inquiry, or experimentation work particularly well when they are face-to-face but are squeezed for time in the curriculum. With that in mind, there’s a strong case for putting delivery of material into pre-session activities including (though not limited to) recordings. Noting that all learning depends on memory and attention, Tracey suggested principles for identifying material from existing lectures which would work better in pre-session videos. To summarise, flipping is most useful where there is a huge variance in prior knowledge, for concepts which students struggle to understand, or key concepts without which students cannot progress.

How do we recognise a good video?

This question exercised us for some time, and yielded a list of attributes of a successful flipped video, which Tracey digested into an evaluation framework, or ‘rubric’, by which to recognise – and so create – a successful video. UCL staff and students can access this on the Flipping the Classroom – Resources Moodle area. To give a flavour of the rubric included the qualities of ambition, sustainability, engagement, quality and orientation.

Next, during the three intervening days, each participant created their own short video intended to enable their lecture to become a dynamic plenary.

Like students, teachers have different needs

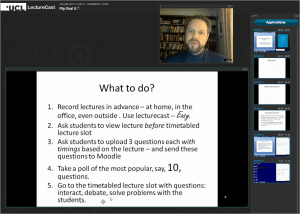

Few Flipped Classroom participants had experience of recording themselves in this way – they faced different constraints and used a variety of different audio-visual recording devices and platforms. Unless they had other preferences, we encouraged them to use UCL’s EchoCapture Personal service to both record and host their video. This allowed them to capture camera, voice and screen from their personal computer. For those who preferred to create and edit outside Lecturecast, we enabled Media Import within Lecturecast as a way of sharing externally-produced video with selected others. Using UCL-hosted software resolves issues of accessibility, service continuity and contingencies and intellectual property, and also provides an optional discussion thread and finer-grained statistics on use than third-party service providers.

As each participant showed their video it became clear that inexperience and relatively low-end technologies were not a barrier to a high standard of video – this was an exciting and motivating discovery. Understandably, not everybody is prepared for their first attempts to be shown and, unless you hear otherwise from their author, those which have been shared need to be approached as proofs-of-concept rather than fully honed learning resources.

Here’s Anne Welsh (Department of Information Studies) on Nox: an Artist’s Book by a Poet:

Here’s Graham Roberts (Department of Computer Science) on Classes and Types:

If you have a UCL account, you can log into Lecturecast to watch Malcolm Galloway (Medical School) introduce astrocytic tumours.

We’ll collect others on the aforementioned Moodle area.

Some of your practical and technical questions answered

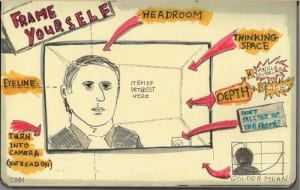

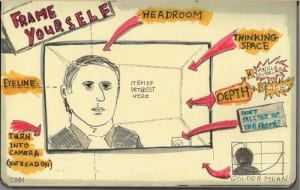

‘Frame yourself’ by Dr Mike Howarth

CALT is active in supporting and promoting flipping and recently held a two-day workshop titled The Media Savvy Academic – Paul Walker summarises the event on UCL’s Teaching and Learning Portal, including some very effective hand-drawn slides – one of which is pictured here – on preparing teaching videos by one of the course leaders, Dr Mike Howarth.

As mentioned above UCL staff can either create video within Lecturecast – UCL’s own service – using EchoCapture Personal, or create externally and upload it to Lecturecast. Why choose Lecturecast? Lecturecast compares well to third-party hosting options – like most it allows commenting and different levels of quality, but in addition it offers finer-grained reporting including hotspots (the parts of a video people are looking at most), and enables you to meet responsibilities and needs related to privacy, security, making sure students can access your recordings, and intellectual property. And not least, ELE knows how to support you using it. If you decide to do the video-making outside Lecturecast, there are a number of freely-available editors available. For Linux OpenShot has been well-received, MovieMaker is Microsoft’s basic and straightforward editor, Apple has the very popular iMovie, and Clive lists a number of tools particularly for narrating and displaying what’s happening on your screen. That’s just a few of the many authoring and editing tools available. If your video has been created outside Lecturecast you just need to contact ele@ucl.ac.uk and ask for Media Import to be enabled on your account.

To do the recording you can use your computer’s inbuilt video and microphone or (if you need a conferencing mic to record an encounter, for example) buy them separately for a modest outlay. It’s not currently possible to directly upload from your mobile phone – but it’s just a few extra steps to download from phone to personal filespace and (assuming you’ve asked for Media Import to be enabled as mentioned above) upload it to Lecturecast from there.

You’ll probably want to edit your video. Originally oriented towards lectures, Lecturecast allows for minimal editing – cutting, basically – for 30 days after upload. In the case of flipping, it may work better for you to create your video outside Lecturecast so you can work on the original editable files when you need to. Alternatives include exporting your video from Lecturecast and incorporating it into other material.

If you’re just recording your screen, do you also need to record your talking face? If you’re really uncomfortable with this, don’t worry – it’s not critical – but some studies indicate (pdf) that the speaker’s visual presence does have a positive effect on students’ attention and affect. Can Lecturecast and Personal Capture stream my video at a sufficiently high quality? Yes, you should be able to get high quality video stream – experiment with the menu to see if it satisfies the level of detail you need.

You’re bound to have other questions – and in any case, things change. So make your first port of call the Lecturecast Resource Centre on UCL’s Wiki, and do get in touch with us (details below).

Find out even more

Tracey has provided some resources including rationale, examples, bibliography, which you can access via the Flipping the Classroom – Resources area on Moodle. There you will also find the evaluation framework (or rubric) for videos which we developed together. If you’re teaching at UCL and interested in experimenting with flipping, E-Learning Environments will be delighted to work with you. Contact us at ele@ucl.ac.uk, 020 3549 5678 (extension 65678). Alternatively drop in for a chat – we are located in the The Podium building (1 Eversholt Street, in front of Euston Station, nearest entrance is on the west side).

During Tracey’s visit we reviewed the evidence supporting flipping. Another aspect of ‘finding out more’ is the much-needed research into flipping. CALT and ELE would love to work with you on evaluating your flipping initiatives – ELE has a dedicated Evaluation Specialist, Dr Vicki Dale, who is waiting to hear from you.

Lastly, we’ve concentrated on video here – audio-only has some distinct benefits – contact ELE to discuss these.

Thanks Tracey!

As things stand, Tracey is now somebody who now knows more about flipping hopes, fears, opportunities and barriers at UCL than practically anybody else. She will be passing this knowledge back to us over the coming weeks and we will disseminate it. We’re very grateful to Tracey for a stimulating, invigorating – and for many, transformative – visit. Her influence at UCL will certainly outlast this brief fortnight.

One of the perennial problems for both academic colleagues and learning technologists is trying to judge the educational value of online courses. Especially in blended learning the online ‘course’ is often just a component of a broader learner experience, and its role really can only be understood in the context of how it supports or extends ‘live’ activities. Thus what looks to a learning technologist like an unsophisticated ‘list of links’ in Moodle may actually support a rich classroom-led enquiry-based learning activity. It is hard to tell without speaking to the lecturer (or students) involved.

One of the perennial problems for both academic colleagues and learning technologists is trying to judge the educational value of online courses. Especially in blended learning the online ‘course’ is often just a component of a broader learner experience, and its role really can only be understood in the context of how it supports or extends ‘live’ activities. Thus what looks to a learning technologist like an unsophisticated ‘list of links’ in Moodle may actually support a rich classroom-led enquiry-based learning activity. It is hard to tell without speaking to the lecturer (or students) involved. Close

Close