Massive online open courses, or MOOCs as they are colloquially know as, can best be described as a mixture of distance learning with the addition of thousands of students, new platforms, generally old teaching methods and a lot of media hype. Yet, they are heralded as a tsunami of change coming to education, the future of learning and a firecracker into institutions who fear they are not able to provide such approaches. Most importantly is that they are largely unproven, mainly due to entering rather new (yet trodden) territory. This post covers some of the history of MOOCs and of my recent experience being a student in one of these courses. It’s fair to say that this big distance learning on a big scale, and what it means for UCL, and education in a wider field, is not known by anyone, but it’s very exciting to watch it unfold, and to look for opportunities of alignment.

What is a MOOC?

An open course where fee-paying and free students mix (or it’s just free) which uses an online learning and teaching environment usually backed by a university or a group of individuals, usually led by top academics. Student numbers are generally not paying a fee and range in numbers between 100 and >150,000 at the moment.

How does it work?

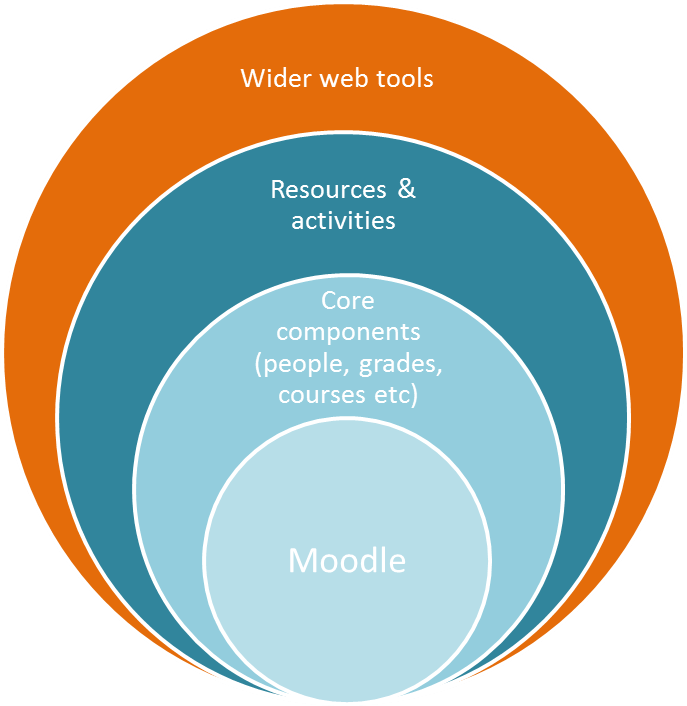

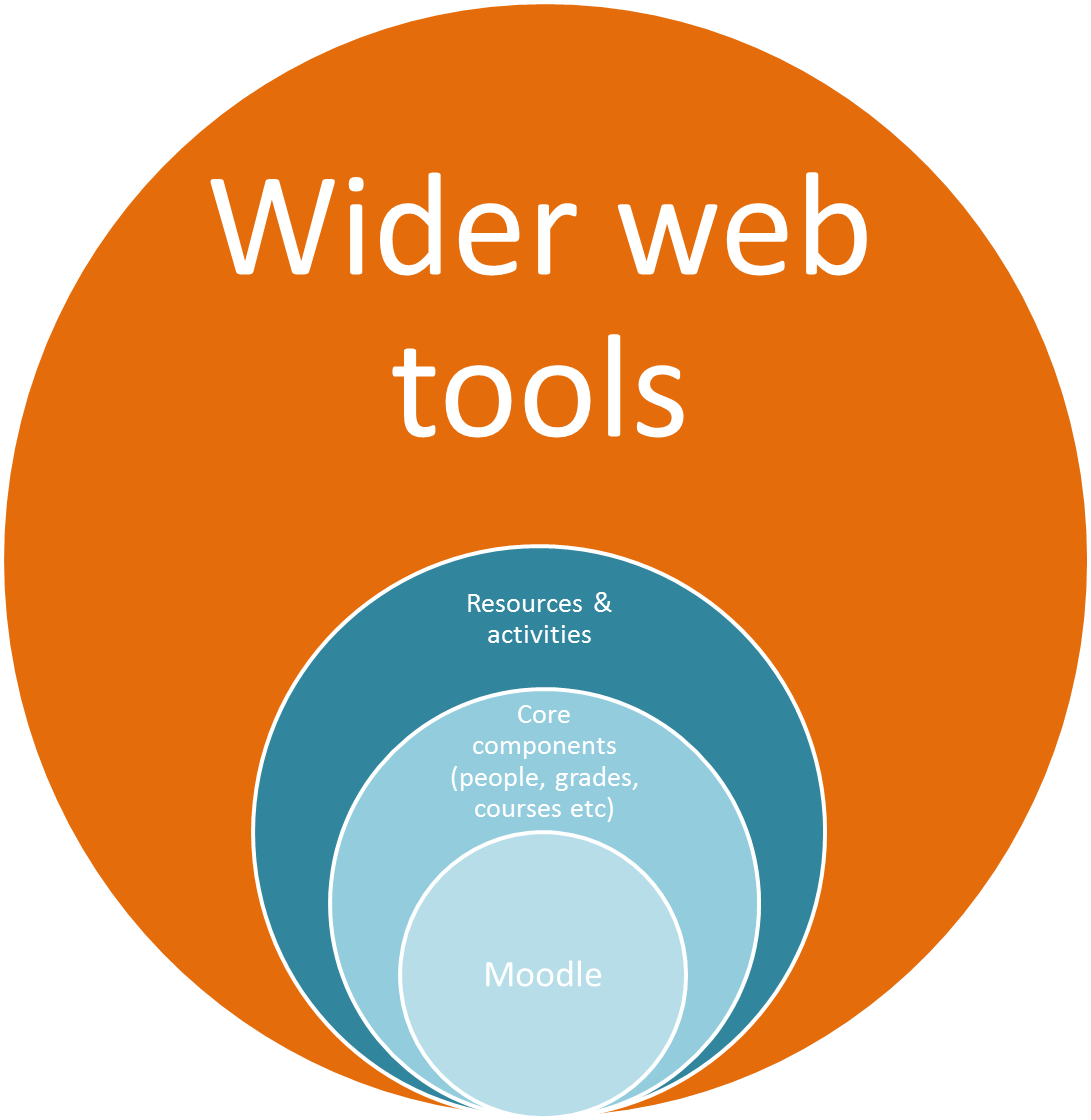

Learning activities are generally asynchronous and follow a flexible structure ensures that promotes students contributions as a core to the learning activity. Usually not using systems such as Moodle but instead tools such as blogs and wikis or bespoke software. Teachers are present, but there has been upwards of 50,000 students per staff member (MITx – Circuits course) so student participation plays a significant part. Systems used reflect this, for example Q&A areas have voting mechanisms and collaborative approaches to answering queries.

Who’s doing it?

They are largely driven by Canadian and US Universities, perhaps due to their initial cost or promotion on western-facing media. Originating in Canada in 2008 and made ‘famous’ by Harvard, MIT, Yale and other elite US universities. Less were discovered from other continents but many exist under the more generic ‘open’ banners of education. Big names include: edX (the recently combined MITx and Harvardx), Coursera. Udacity and more.

Why is it significant?

A MOOC opens a course and invites anyone to enter, resulting in a new learning dynamic for collaborative and conversational opportunities for students to gather and discuss the course content. A new pedagogy has been associated entitled Connectivism (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Connectivism) and edX, potentially the largest MOOC identified will use it as a massive educational research tool to benefit the institution’s in-house learning and teaching, among other things.

The downsides?

The non-traditional dynamic of a MOOC may make some students uneasy, particularly those who expect, or thrive, on a high level of interaction with the teacher. Students with no financial stake or educational background in the course may bring a different, potentially disruptive, approach. Teachers must rethink the at least some of the course’s elements to take advantage of a MOOC, giving particular consideration to the technical and structural demands and logistics of running such a course. Learners and academics may oppose this style of learning and teaching and demand more traditional approaches.

Implications for teaching and learning

MOOCs present a new opportunity for an independent, life-long learner. By removing the risk attached to a course, it may encourage participation from those who are less-likely to enrol in the traditional educational methods. “The most significant contribution is the MOOC’s potential to alter the relationship between learner and instructor and between academe and the wider community” – http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ELI7078.pdf

Being a MOOC Student Coursera homepage

Six months ago I blogged about being an MITx student and now I am undertaking a wider programme of study through Corsera – a similar platform founded by two professors from Stanford; Daphne Koller and Andrew Ng. The course I am taking at the moment is Internet History, Technology and Security. We’re up to week five and it’s going well so far, I think.

Six months ago I blogged about being an MITx student and now I am undertaking a wider programme of study through Corsera – a similar platform founded by two professors from Stanford; Daphne Koller and Andrew Ng. The course I am taking at the moment is Internet History, Technology and Security. We’re up to week five and it’s going well so far, I think.

The main direct tuition I’ve received has been via recorded videos of either Dr. Chuck (Charles Severance) and other resources, mostly video based. They have a nifty feature whereby as the video progresses it stops to ask a question – this is clearly indicated on the timeline for the video (see screenshots). After some feedback the video continues. This helps break up the didactics but it’s obvious (even to the founders) that this isn’t directly innovative but it’s a little step forward than just a video. In addition is the ability to control the playback of the video, increasing the speed to 1.75x or 2x of the original.

Videos in Coursera - answering a question

Interaction

With so many students MOOCs can’t have teaching staff interact directly with the students for all conversations / questions. With this in mind, the discussion forum (much like MITx) employed a rating system where all questions can also be rated (and flagged). There are many students answering one another’s questions, and this is widely encouraged. Additionally there is a wiki, although this is used less. Surprisingly, for an online course, there’s a lot of face to face interaction where students form study groups and meet in cities across the globe. Lastly, with one teacher and over 10,000 students there’s little chance for much else, but Dr. Chuck is still offering contact hours by arranging meetings in coffee shops across America.

Assessment

So far we have had a quiz most weeks, where 10 MCQ questions can be answered – nothing special to report here. The peer-assessment worked rather well, with the submission of a short essay after week one each student had to use a grading rubric for at least five other students, and give written feedback. After leaving mine for seven students I eventually got my feedback, it was a mixed bunch of reviews of my work, from excellent to rubbish – so I averaged it overall. Needless to say this approach is understandable, but not necessarily meaningful for my learning, especially when considering the potential lack of investment from the students either fiscally or effort-wise.

Personal contribution

I’m not putting much into this MOOC, I know the subject fairly well and it’s more of a learning journey into distance learning / MOOCs than it is about Internet History, Technology and Security. I don’t think it’s a problem how much I put in, as the course is designed to fit with my life, not the other way around. As I am also studying for my masters, I instantly see a difference between this seven week course, and say, a 15-credit module. I’m sure a lot of people are learning a lot more than me from this course, and that is obviously wonderful. It’s early days for MOOCs and these courses are all forming the next steps of what they will evolve into. I am sure during this course the platform is developing, the teachers are learning and the data collected is showing what’s working, and who isn’t (ahem).

The future?

MOOCs are still emerging and somewhat undefinable at this stage. The usual trending phenomena warnings are present, as are the ‘unknown’ opportunities. As the buzz fades and MOOCs evolve the expectations and methods are likely to stabilise, thus making them more consistent and definable. Universities may be ‘too slow’ to realise the potential, or not get caught up in the buzz, potentially wasting significant resource. As the world becomes more connected, and education opens up, there is an echo of this being a permanent and positive change to higher education.

Other choice resources

There’s a whole load of commentary on MOOCs, here’s some of the best so far:

Learning for Free? MOOCs by Mira Vogel, Goldsmiths. Presented at their Future Tense 2012 conference.

The Campus Tsunami by David Brooks, New York Times

What’s right and what’s wrong about Coursera-style MOOCs by Tony Bates, Research Associate, Contact North

MOOC pedagogy: the challenges of developing for Coursera by Jeremy Knox, Sian Bayne, Hamish MacLeod, Jen Ross and Christine Sinclair, MSc in E-learning Programme Team, University of Edinburgh

Close

Close

Six months ago I blogged about

Six months ago I blogged about