Reflections before UCL’s first Mooc

By Matt Jenner, on 26 February 2016

UCL’s first Mooc – Why We Post: The Anthropology of Social Media launches on Monday on FutureLearn. It’s not actually our first Mooc – it’s not even one Mooc, it’s 9! Eight other versions are simultaneously launching on UCLeXtend in the following languages: Chinese, English, Italian, Hindi, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil and Turkish. If that’s not enough we seem to have quite a few under the banner of UCL:

- UCLeXtend ~ Introduction to Digital Curation – Jenny Bunn (UCL DIS)

- Coursera ~ English Common Law -Hazel Genn (UCL Laws) with Uni of London International Programme

- FutureLearn ~ Unlocking Film Rights: Understanding UK Copyright – Prodromos Tsiavos (UCL Comp Sci.) with Creative Skillset as lead partners

- FutureLearn ~ Blended Learning Essentials (two parts) – Diana Laurillard (IOE, LKL) with Leeds as lead partners

- FutureLearn ~ Why We Post: The Anthropology of Social Media – Danny Miller (and many others) (UCL Anth.)

- FutureLearn ~ The Many Faces of Dementia – Tim Shakespeare (UCL Neurology)

- FutureLearn ~ Making Babies in the 21st Century – Dan Reisel (UCL Child Health) (to be announced)

- Coursera ~ ICT in primary education – Diana Laurillard (IOE LKL) in partnership with UoL IP

- Coursera ~ Supporting Children in Reading and Writing – Jenny Thomson and Vincent Geotry (UCL IOE) with University of London

- Coursera ~ What Future for Education – Clare Brooks (UCL IOE) with University of London

- Coursera ~ Enhance your career and employability skills – UCL Careers Group and David White (University of London) with UoL as partners

- Digital Business Academy ~ Size up your idea – Dave Chapman (UCL School of Management) with TechCityUK

- Digital Business Academy ~ Set up a Digital Business – Dave Chapman (UCL School of Management) with TechCityUK

(quite a few of these deserve title of ‘first’ – but who’s counting…)

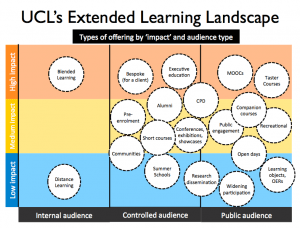

UCL is quite unique for some of these – we have multiple platforms which form a part of our Extended Learning Landscape. This maps out areas of activity such as CPD, short courses, Moocs, Public Engagement, Summer Schools (and many more) and tries to understand how we can utilise digital education / e-learning with these (and what happens when we do).

Justification for Moocs

We’ve not launched our first Mooc (apparently) but we also need to develop a mid term plan too – so we can do more. Can we justify the ones we’ve done so far? Well a strong evaluation will certainly help but we also need an answer to the most pertinent pending question:

How much did all this cost and was it worth it?

It’s a really good question, one we started asking a while ago, and still the answer feels no better than educated guesswork. Internally we’re working on merging a Costing and Pricing tool (not published, sorry) and the IoE / UCL Knowledge Lab Course Resource Appraisal Modeller (CRAM) tool. The goal is to have a tool which takes the design of a Mooc and outputs a realistic cost. It’s pretty close already – but we need to feed in some localisations from our internal Costing and Pricing tool such as Estates cost, staff wages, Full Economic Costings, digital infrastructure, support etc. The real cost of all this is important. But the value? Well…

Evaluation

We’ve had a lot of ideas and thoughts about evaluation; what is the value of running Moocs for the university? It feels right to mention public engagement, the spirit of giving back and developing really good resources that people can enjoy. There’s the golden carrot being dangled of student recruitment but I can’t see that balancing any Profit/Loss sheets. I do not think it’s about pedagogical innovation, let’s get real here: most Moocs are still a bulk of organised expert videos and text. I don’t think this does a disservice to our Moocs, or those of others, I’d wager that people really like organised expert videos and text (YouTube and Wikipedia being stable Top 10 Global Websites hints at this). But there are other reasons – building Moocs is an new way to engage a lot of people with your topic of interest. Dilution of the common corpus of subjects is a good thing; they are open to anyone who can access them. The next logical step is subjects of fascination, niche, specialist, bespoke – all apply to the future of Moocs.

For evaluation, some obvious things to measure are:

- Time from people spend on developing the Mooc – we’ve got a breakdown document which tries to list each part of making / running a Mooc so we can estimate time spent.

- Money spent on media production – this one tends to be easy

- Registration, survey, quiz, platform usage and associated learner data

- Feedback from course teams on their experience

- Outcomes from running a Mooc (book chapters, conference talks, awards won, research instigated)

- Teaching and learning augmentation (i.e. using the Mooc in a course/module/programme)

- Developing digital learning objects which can be shared / re-used

- Student recruitment from the Mooc

- Pathways to impact – for research-informed Moocs (and we’re working on refining what this means)

- How much we enjoyed the process – this does matter!

Developing a Mooc – lessons learned

Communication

Designing a course for FutureLearn involves a lot of communication; both internally and to external Partners, mostly our partner manager at FutureLearn but there are others too. This is mostly a serious number of emails – 1503 (so far) to be exact. How? If I knew I’d be rich or loaded with oodles of time. It’s another new years resolution: Stop: Think: Do you really need to send / read / keep that email? Likely not! I tried to get us on Trello early, as to avoid this but I didn’t do so well and as the number of people involved grew adding all these people to a humungous Trello board just seemed, well, unlikely. Email; I shall understand you one day, but for now, I surrender.

Making videos

From a bystander’s viewpoint I think the course teams all enjoyed making their videos (see final evaluation point). The Why We Post team had years to make their videos in-situ from their research across the world. This is a great opportunity to capture real people in the own context; I don’t think video gets much better than this. They had permission from the outset to use the video for educational purposes (good call) and wove them right into the fabric of the course – and you can tell. Making Babies in the 21st Century has captured some of the best minds in the field of reproduction; Dan Reisel (lead educator) knows the people he wants, he’s well connected and has captured and collated experts in the field – a unique and challenging achievement. Tim Shakespeare, The Many Faces of Dementia, was keener to capture three core groups for his course: people with Dementia, their carers / family and the experts who are working to improve the lives for people with Dementia. This triangle of people makes it a rounded experience for any learner, you’ll connect with at least one of these groups. Genius.

Also:

- Audio matters the most – bad audio = not watching

- Explain and show concepts – use the visual element of video to show what you mean, not a chin waggling around

- Keep it short – it’s not an attention span issue, it’s an ideal course structuring exercise.

- Show your face – people still want to see who’s talking at some point

- Do not record what can be read – it’s slower to listen than it is to read, if your video cam be replaced with an article, you may want to.

- Captions and transcripts are important – do as many as you can. Bonus: videos can then be translated.

Using third party works

Remains as tricky as it ever has been. Moocs are murky (commercial? educational? for-profit?) but you’ll need to ask permission for every single third-party piece of work you want to use. Best advice: try not to or be prepared to have no response! Images are the worst, it’s a challenge to find lots of great images that you’re allowed to use, and a course without images isn’t very visually compelling. Set aside some time for this.

Designing social courses that can also be skim-read

FutureLearn, in particular, is a socially-oriented learning platform – you’ll need to design a course around peer-to-peer discussion. Some is breaking thresholds – you’re trying to teach them something important, enabling rich discussion will help. You’re also trying to keep them engaged – so you can’t ask for a deep, thoughtful, intervention every 2 minutes. Find the balance between asking important questions – raising provocative points – and enjoying the fruits of the discussion with the reality of ‘respond if you want’ type discussion prompts.

Connect course teams together

While they might not hold one another’s hair when things get rough – the course teams will benefit from sharing their experiences with one another. We’ve held monthly meetings since the beginning, encouraging each team to attend and share their updates, challenges, show content, see examples from other courses and generally make it a more social experience. Some did share their dropboxes with one another – which I hadn’t expected but am enjoying the level of transparency. I am guilty of thinking at scale at the moment, so while I was guiding and pseudo ‘project-managing’ the courses, I was keen to promote independence and agency within the course teams. It’s their course, they’ll be the ones working into the night on it, I can’t have them relying on me and my dreaded inbox. The outcome is they build their own ideas and shape them in their own style; maybe we’re lucky but this is important. We do intervene at critical stages, recommending approaches and methods as appropriate.

Plan, design and then build

Few online learning environments make good drafting tools. We encouraged a three-stage development process:

- Proposals, expanded into Excel-based documents. Outlines each week, the headline for each step/component and critical elements like discussion starters.

- Design in documents – Word/Google Docs (whatever) – expand each week; what’s in each step. Great for editorial and refinement.

- Build in the platform.

The reason for this is the outlines are usually quick to fix when there’s a glaring structural omission or error. The document-based design then means content can be written, refined and steps planned out in a loose, familiar tool. Finally the platform needs to be played with, understood and then the documents translated into real courses. It’s not a solid process and some courses had an ABC (Arena Blended Connected) Curriculum Design stage, just to be sure a storyboard of the course made sense.

Overall

- It’s hard work – for the course teams – you can just see they’ll underestimate the amount of time needed.

- The value shows once you go live and people start registering, sharing early comments on the Week 0 discussion areas.

- These courses look good and work well as examples for others, Mooc or credit-bearing blended/online courses

- Courses don’t need to be big – 1/2 hours a week, 2-4 weeks is enough. I’d like to see more smaller Moocs

- Integrating your Moocs into taught programmes, modules, CPD courses makes a lot of sense

As a final observation before we go live with the first course: Why We Post: The Anthropology of Social Media, on Monday there was one thing that caught my eye early:

Every course team leader for our Moocs is primarily a researcher and their Moocs are produced, largely, from their research activity. UCL is research intensive, so this isn’t too crazy, but we’re also running an institutional initiative the Connected Curriculum which is designed to fully integrate research and teaching. The Digital Education team is keen to see how we build e-learning into research from the outset. This leads us to a new project in UCL entitled: Pathways to Impact: Research Outputs as Digital Education (ROADE) where we’re exploring research dissemination and e-learning objects and courses origins and value. More soon on that one – but our Mooc activity has really initiated this activity.

Coming soon – I hope – Reflections after UCL’s first Mooc 🙂

Close

Close

Six months ago I blogged about

Six months ago I blogged about