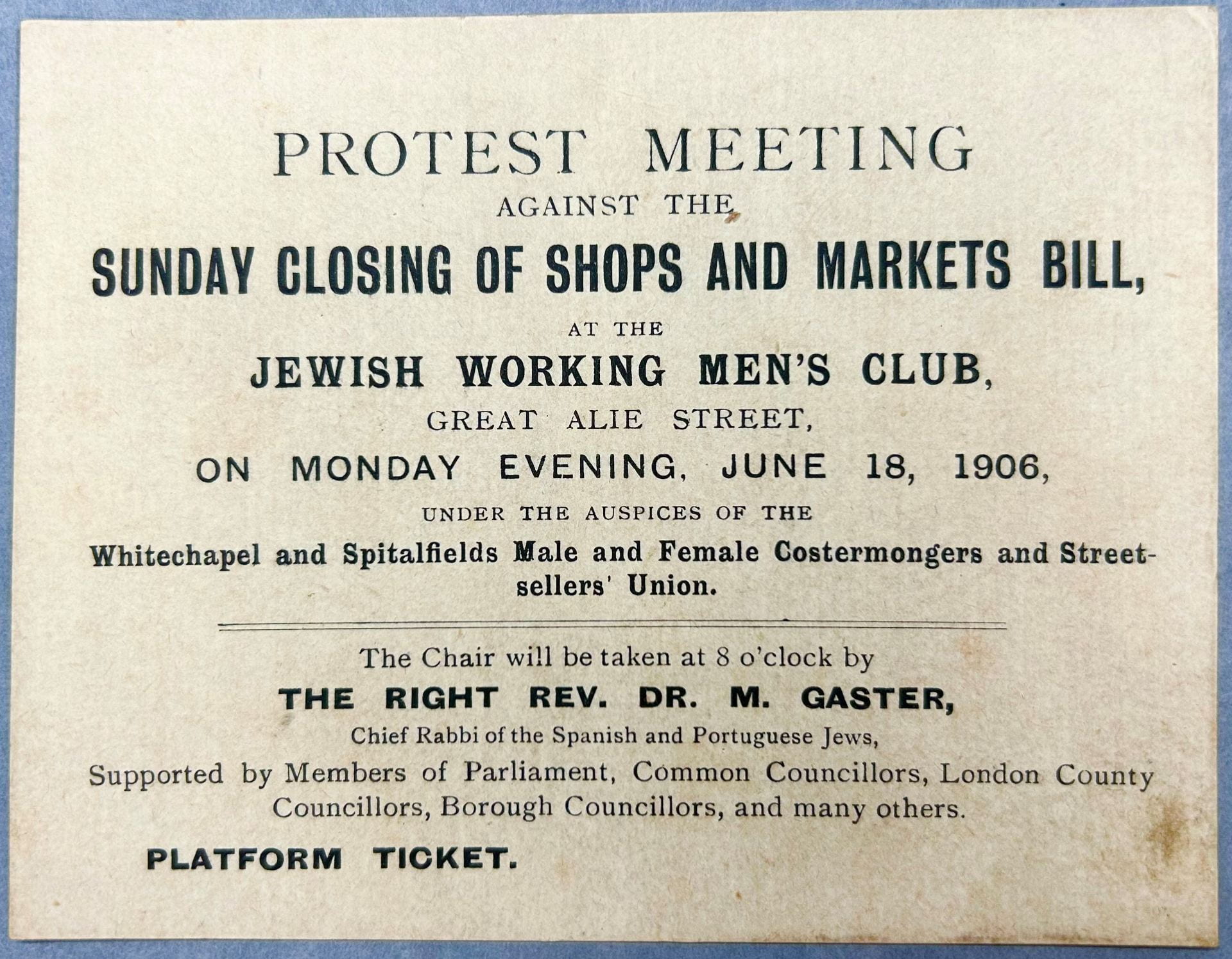

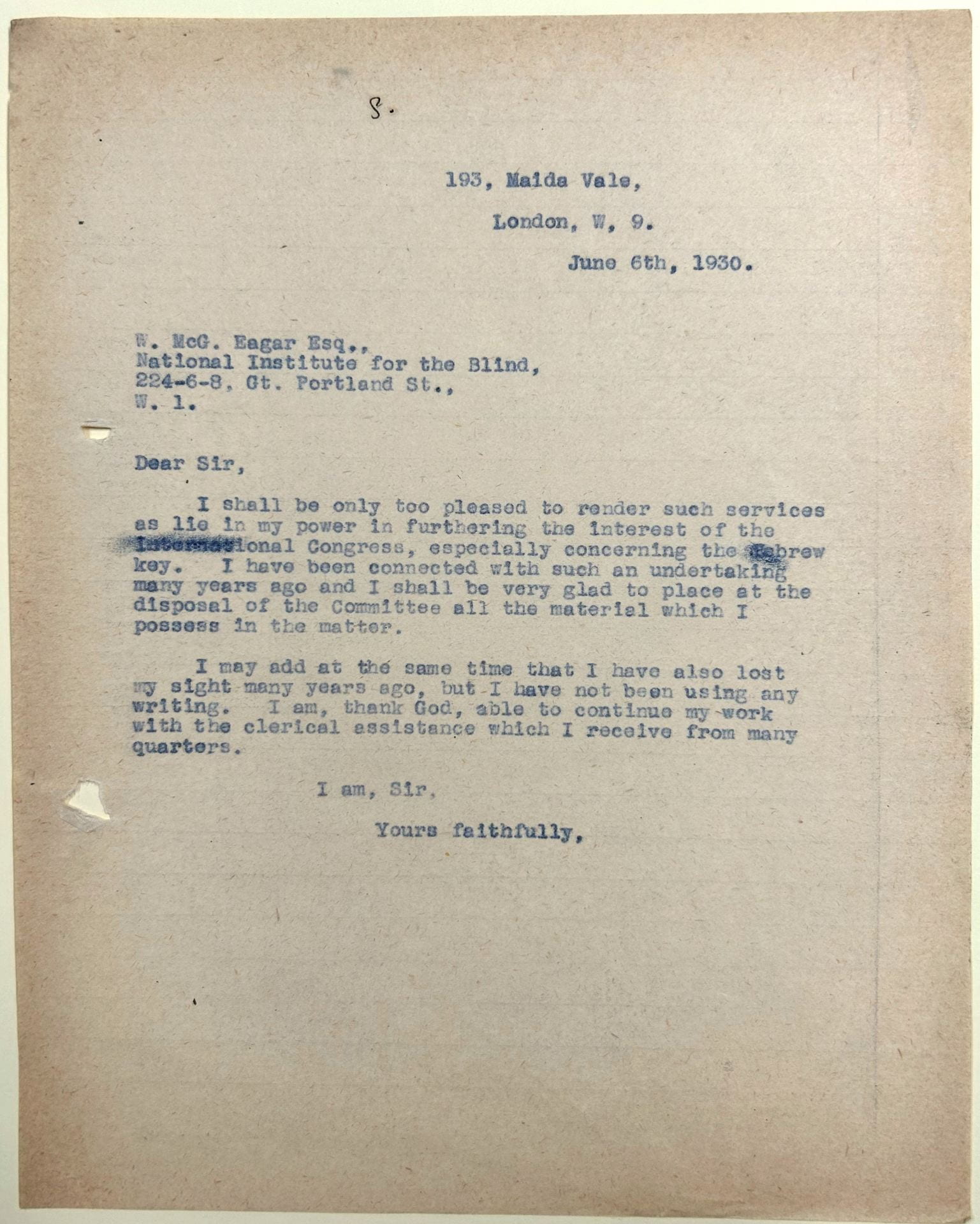

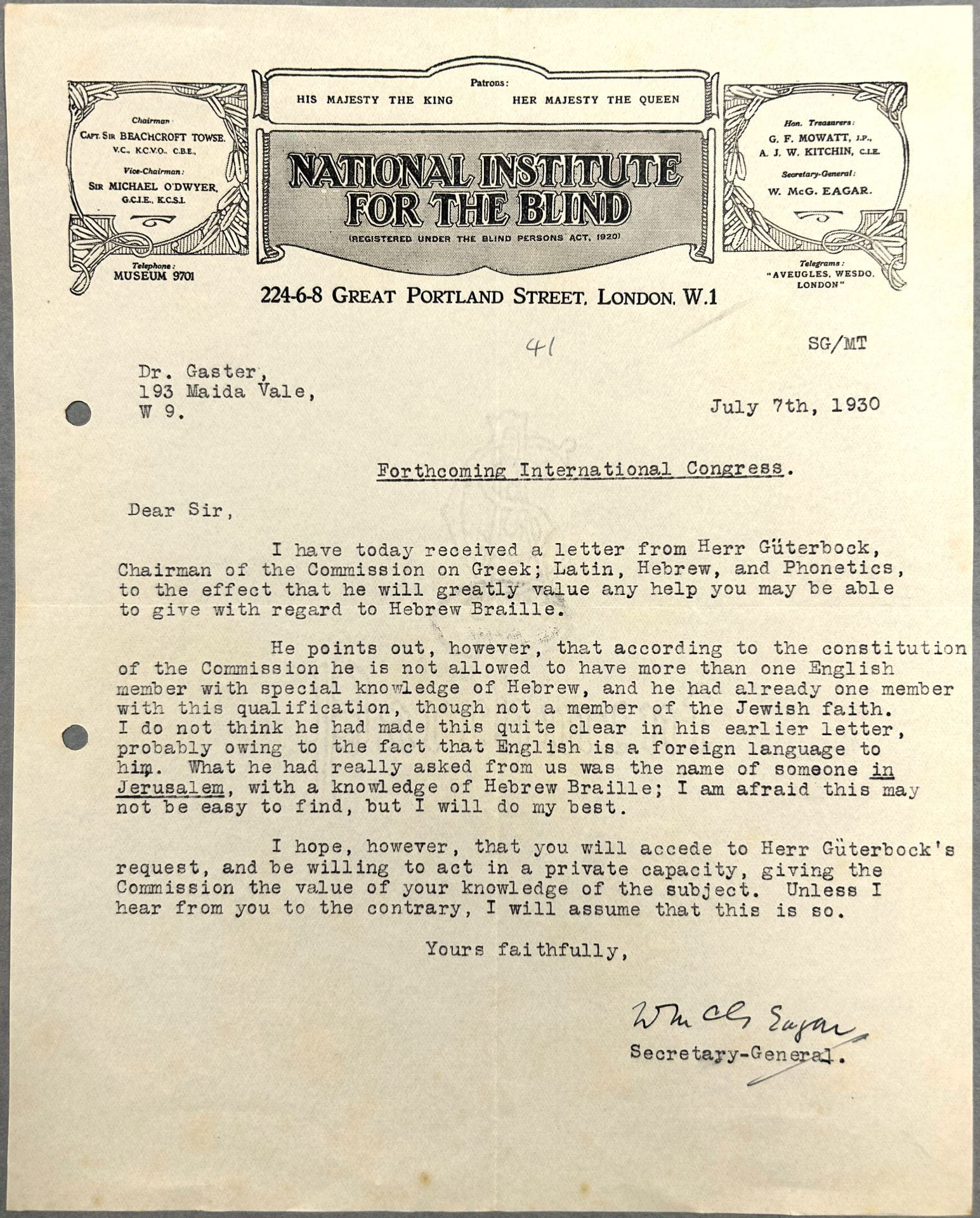

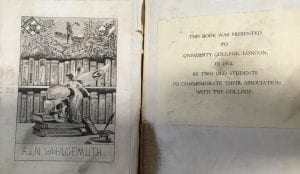

In our previous blog post we introduced our project to catalogue the archive of Moses Gaster, and looked at some of the letters sent to Gaster on topics as diverse as Sunday trading and Hebrew braille. In the second of our two posts relating to the project, Gaster Project Cataloguer Israel Sandman discusses Gaster’s charitable activities.

From the Gaster Archives: A Glimpse into Moses Gaster’s Charity Activities

By Dr Israel M. Sandman, Gaster Project Cataloguer

Moses Gaster was a multifaceted person. He was the chief rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in London, and, by extension, of all Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ congregations under the British Empire. He was a polymath academic scholar, with strong focuses on comparative folklore and linguistics. He was a key figure in the emergence of modern Zionism. And he was a go-to person for Jews worldwide, for help with their various needs and wants.

Charity Appeals to Gaster:

Daily, Moses Gaster received multiple charity appeals, some in the post, and some in person during his reception hours. While he donated from his personal funds to Jewish and other worthy causes, as seen in receipts, lists of donors, and gentle reminders to honour his pledges, what he could do from his own funds was a mere drop in the ocean of need.

![[Image and Transcription of Receipt for Donation made by Gaster (file 131, item 44)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2918-1024x652.jpg)

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 131/44]

Charitable Funds on a Community Level:

Addressing the vast needs faced by people in fincial hardship required charitable funds on a community level. Charitable funds established in the Jewish community enabled Gaster to help the Jewish individuals and worthy institutions that turned to him from Palestine, North Africa, elsewhere in the Near East, India, West Indies, Eastern and Central Europe, the East End of London, the length and breadth of Britain, and elsewhere. We shall examine two such funds, one of which was well established, and another of which was an ad-hoc fund set up to meet a specific need.

Case 1: Gaster Helps S. Edelstein via the Board of Guardians of the Poor of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue:

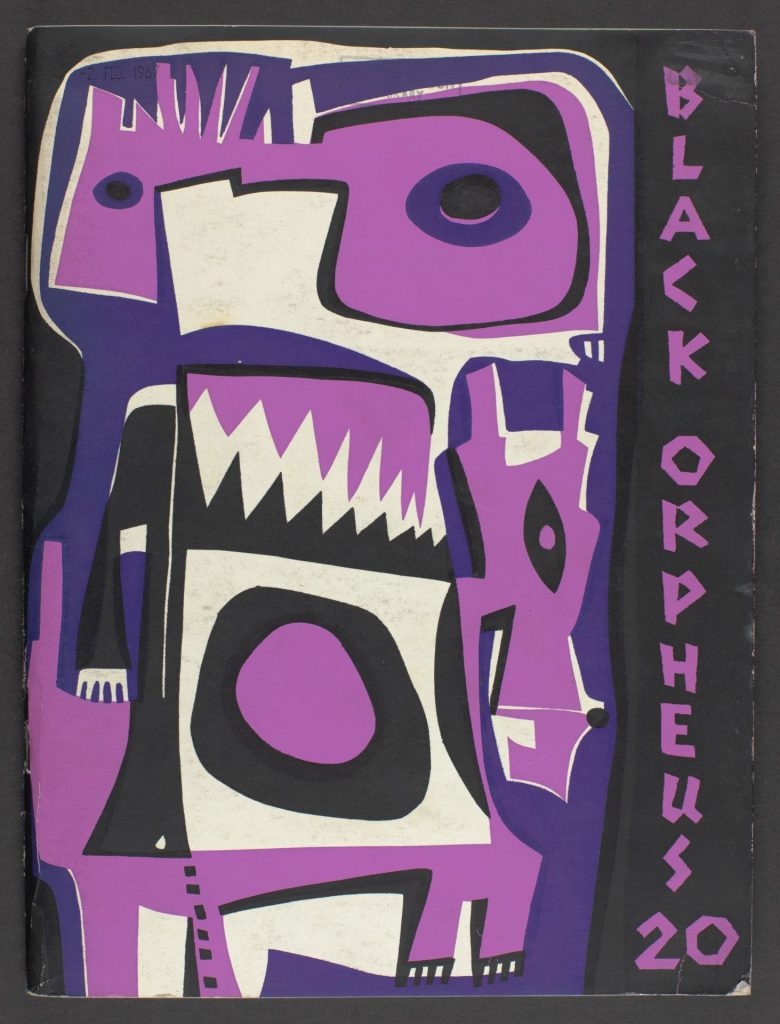

Shalom Edelstein was a Romanian Jew residing in London’s East End, which at the turn from the 19th to the 20th century was the first place of settlement for many Jews from Central and Eastern Europe. Reading between the lines of Edelstein’s 21 March 1899 postcard to Gaster, written in ornate Hebrew full of allusions to classical Jewish literature, and in which he mentions his ill health, one gets the impression that Edelstein was more a man of the mind than a man of the body, and that he shared interests with his “landsman” Gaster.

London 21/4/99

כבוד הרב החכם הבלשן

סופר מהיר בלשונות החיות, רב ודרשן

לעדת הפורטוגעזים, בעיר הבירה לונדן,

והמדינה וע”א כש”ת מו[“]ה ד.ר. גאשטער נ”י.

הנני בזה לכתוב למ”כ

את רשומתי, כמו שבקש מאותי, אולי יאבה

לכבדני במכתבו, ומפני כי מעת ראיתי פני

כ”מ, לא נתחדש שום דבר, – רק שאני חלש

מאד, ואנני בקו הבריאה, עד כי בכבדות

אוכל לקום ממשכבי, – לכן אקצר

ואומר שלום.

והנני מוקירו ומכבדו כערכו הרם.

פ”ש, כשמי, – שלום

הן תוי ונוי

S. Edelstein

17 Winterton St.

Commercial Road, E. |

![Image of S. Edelstein’s 21 March 1899 Mostly Hebrew Postcard to Gaster (file 117, item 9)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2919-238x300.jpg) |

| London 21/4/99

His honour, rabbi, sage, linguist, speedy scribe in living languages, rabbi and preacher to the congregation of Portuguese [Jews] in the capital city London and the [entire] country, and furthermore [possessor of] the ‘crown of Torah’, our Master Rabbi Dr Gaster, may his lamp shine!

I am hereby writing my address [Hebrew: רשומתי or רשימתי] to his honour, as requested by him. Perchance he will desire to honour me with a letter? On account of the fact that since I have seen his honour’s face, nothing new has occurred – aside from my being very weak: I am not keeping in good health, so much so that it is only with difficulty that I can arise from my couch – I will therefore be brief, and say ‘farewell’ [Hebrew: Shalom].

I hereby hold him precious and honour him, in keeping with his lofty worthiness,

Greetings of Shalom, in keeping with my name, Shalom [Peace], being my mark and my charm

S. Edelstein

17 Winterton St.

Commercial Road, E. |

[Image, Transcription, and Translation of S. Edelstein’s 21 March 1899 Mostly Hebrew Postcard to Gaster. UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1. Formerly file 117, item 9]

Multiple Communications Between Edelstein and Gaster:

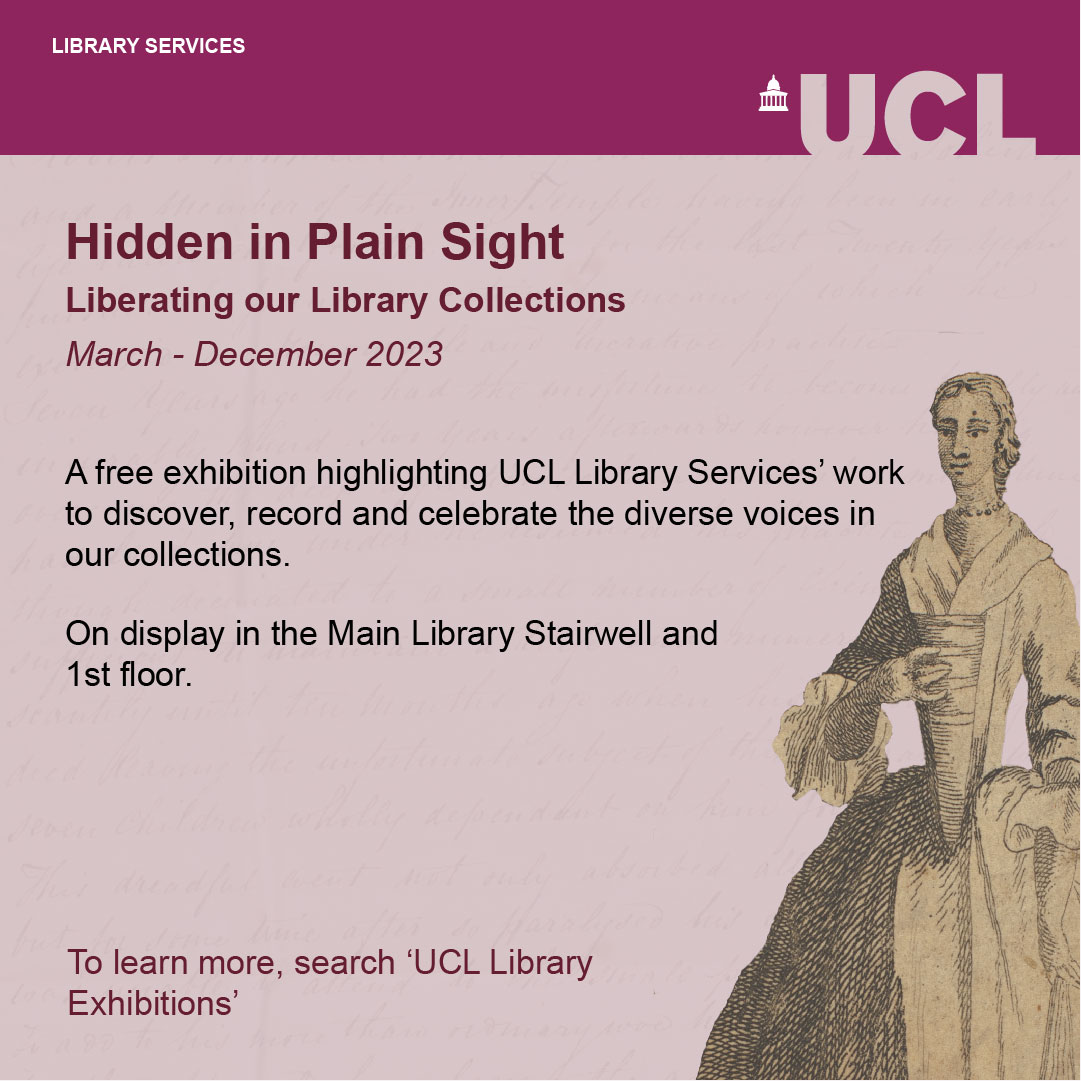

This was not their first communication. In the postcard, Edelstein refers to their having had a face-to-face meeting; and he notes that Gaster had asked him for his reshuma / רשומה [or: reshima / רשימה], presumably meaning his address. Presumably, this indicates that Edelstein had asked Gaster for assistance; and that Gaster was going to try and help him. Three days later, on 24 April 1899, Edelstein sent another postcard to Gaster, this one in Romanian. Apparently, to help Edelstein, Gaster turned to the charity board of the synagogue of which he was rabbi, the Board of Guardians of the Poor of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue.

![[S. Edelstein’s 24 March 1899 Romanian Postcard to Gaster (file 117, item 20)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2920-1024x799.jpg)

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archives, GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 117/20]

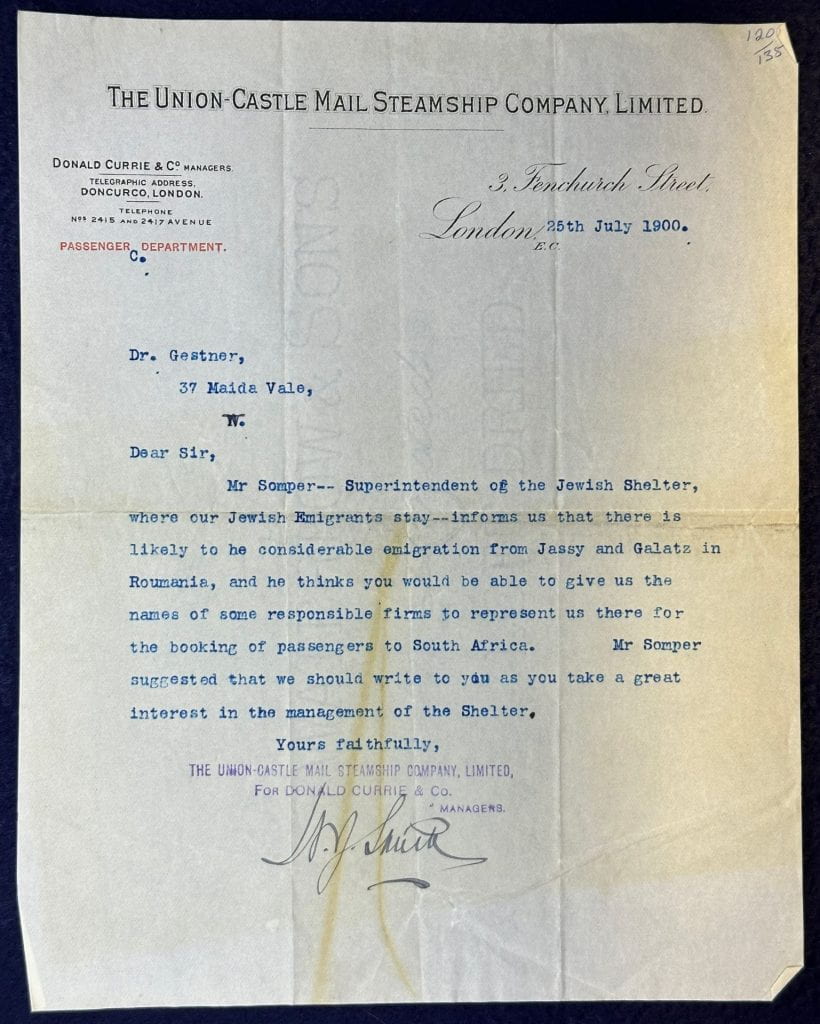

The Board of Guardians’ Approval:

Nine days later, on the 3rd of May, Gaster received a memo from the Board of Guardians. They would cover Edelstein’s train fare from London to Liverpool, and his boat fare from Liverpool to New York. However, that cost £5, and they did not have anything additional to offer Edelstein. Although that would mean that Edelstein would arrive penniless in New York, the Board had reason to believe that Edelstein would nonetheless be admitted to the USA. It seems that Edelstein was permitted to enter the United States, for we have a long letter, in Romanian, which he sent to Gaster from New York. Towards the end of that letter, he updates Gaster about a certain D. Gottheil. The Gaster Archive contains letters to Gaster from a Professor Richard Gottheil, relevant to the writing of Jewish Encyclopedia articles and possibly to Zionism; but it is unclear whether there is a link from Richard to D. Gottheil.

London May 3rd 1899

Dear Dr. Gaster,

re – S. Edelstein

With difficulty I succeeded in securing a passage for this man per “Tonfariro” which will sail from Liverpool on Saturday next. The fare came to £5 which includes railway fare to Liverpool so that I have nothing to hand over to the man. I am informed that by this line it is not necessary for him to have a certain sum of money in his pocket on arrival in New York.

Yours faithfully,

J.Piza

The Board

would do nothing

for Haham Abohab

J.P.

[UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1. Formerly file 118/11]

The Limitations of Working Through the Board of Guardians of the Poor:

In addition to the limits of what the Board felt capable of doing for Edelstein, at the end of their memo, the chairman adds an apologetic side note. He mentions that the Board did not approve a different request, for funding for a certain Hakham (rabbi/sage) Abohab. It is noteworthy that Edelstein was a Central / Eastern European Jew, while the name Abohab indicates a Jew from the Islamic countries. Although the Spanish and Portuguese tradition is more aligned with the traditions of the Islamicate Jews, the Spanish and Portuguese Board approved Edelstein’s request, not Abohab’s. This seems to indicate an objectivity on the part of the Board. It appears that the reason for the Board’s limits in giving was the fact that the Synagogue was experiencing financial difficulties; and in order for Gaster to carry out his wide range and full scale of charitable activities, he needed additional sources of funding, beyond those available through his own congregation

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 131/85]

Dear Sir,

The Gentlemen of the Mahamad [executive committee] invite your attention to the Statements of Accounts of the Synagogue, and the Report of same for the year 1899, which have been circulated amongst the Yehidim [members] of the Congregation, & I have particularly to point out that the result of the year’s working shews a deficit of £595.-, and that the Elders have been compelled to sell out Capital Stock to meet this & other deficiencies accrued since 1895, amounting in the aggregate to £1608.-

This position, which is a very serious one, was duly considered by the Elders at their recent Annual Meeting, and they requested the Mahamad to take such steps as they might think necessary, to call attention, in the first instance …

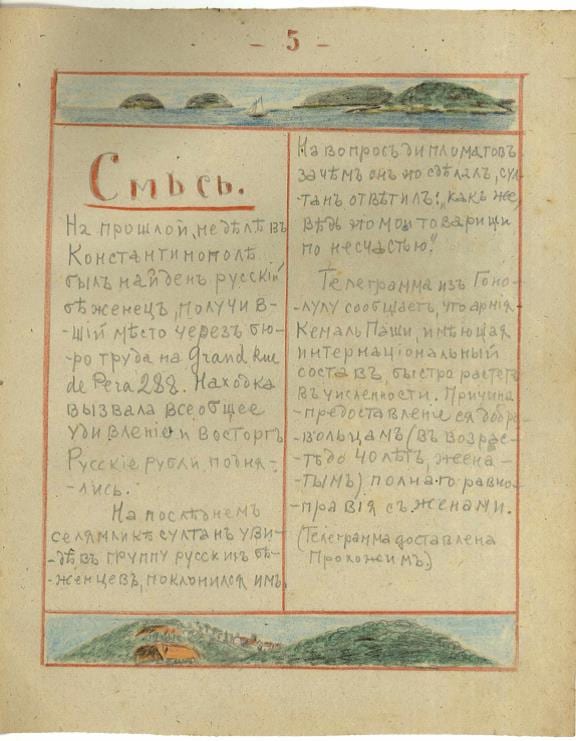

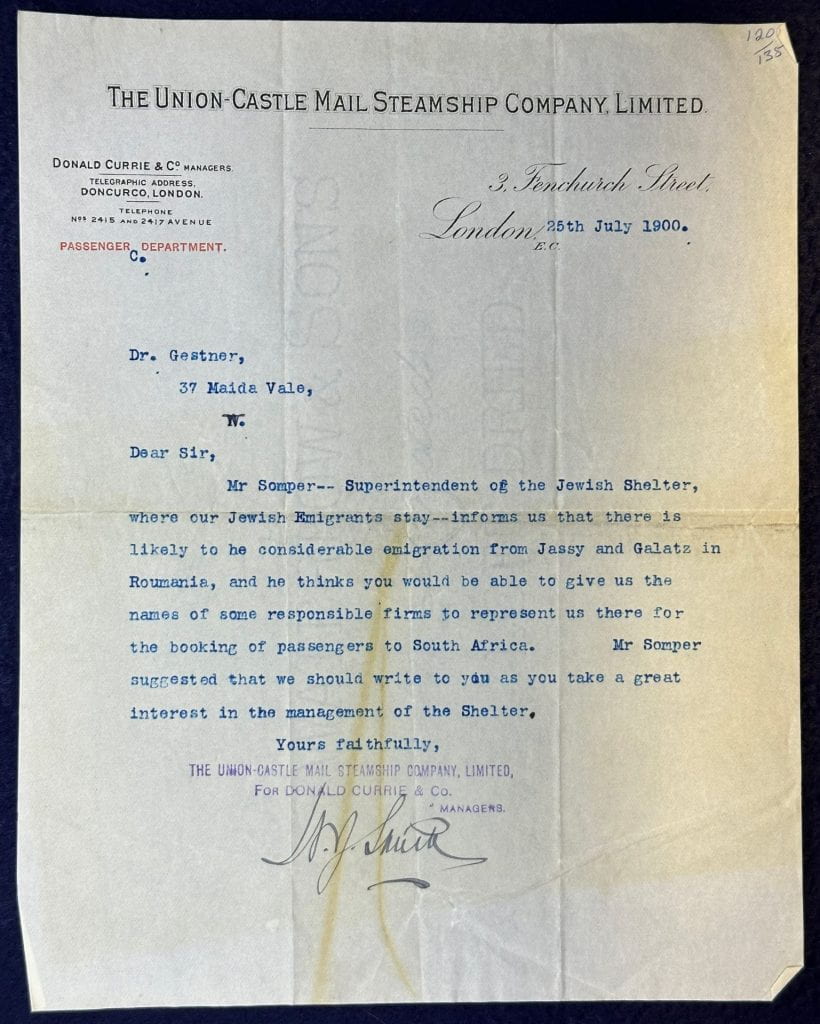

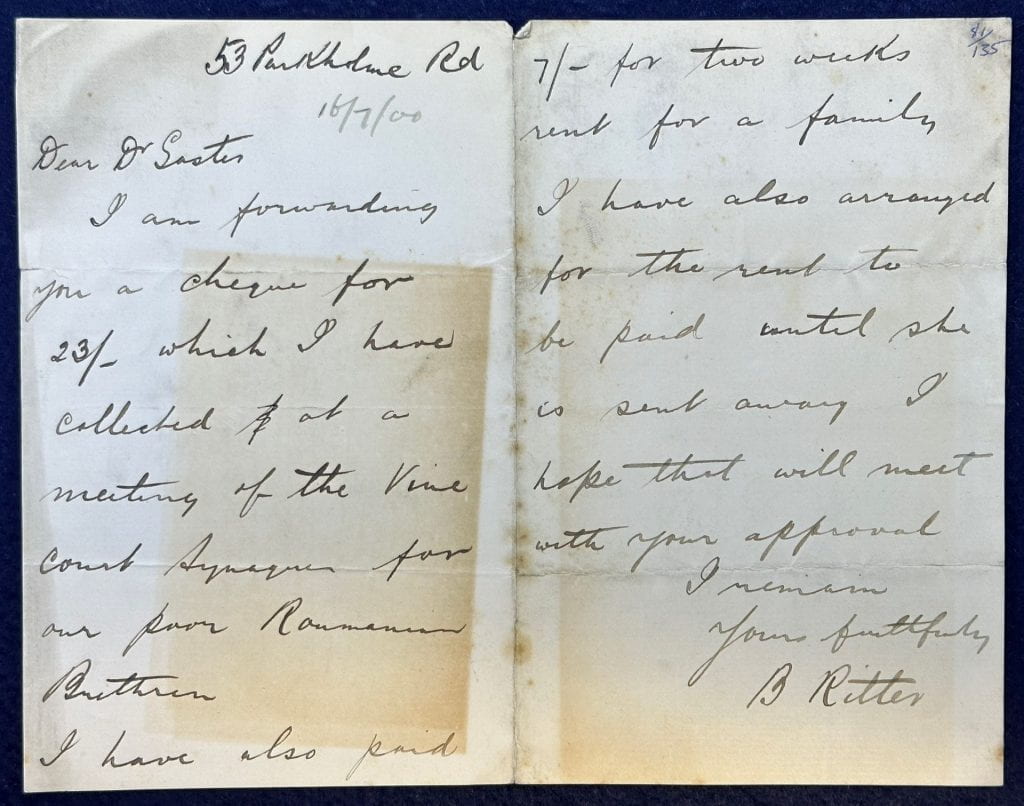

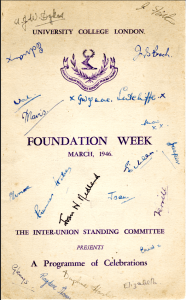

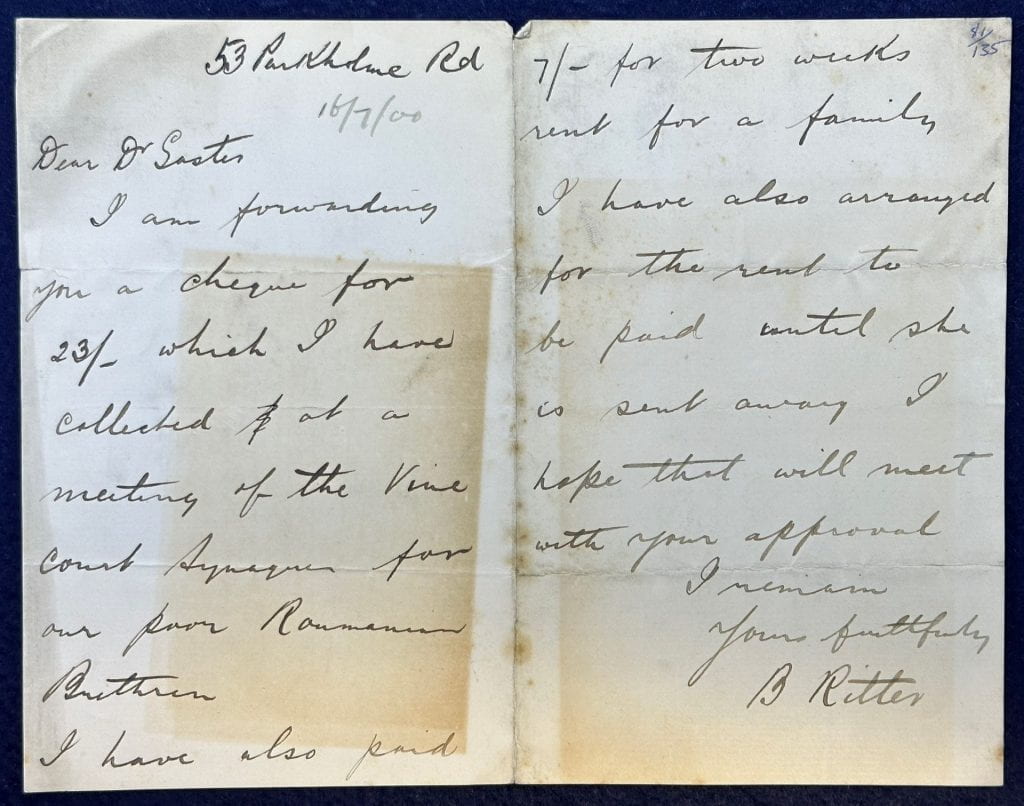

The Ad Hoc Fund for “Our Poor Roumanian Brethren”:

The Crisis of Romanian Jewry:

One additional source of charity funds, independent of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue and its Board of Guardians, is an ad hoc fund that Gaster seems to have created himself. The fund is for ‘our poor Roumanian Brethren’, as described in Benjamin Ritter’s letter to Gaster, accompanying a cheque from a collection taken up in Vine Court Synagogue. At this juncture (around 1900), Romanian Jews were experiencing an unusual level of persecution, and were seeking to leave Romania. From all directions, individuals and institutions were turning to Gaster for solutions and financial help; and Gaster did respond.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive. GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 135/20]

The Vine Court Synagogue:

The Vine Court Synagogue was a congregation of Eastern European Jews, in the Whitechapel section of London’s East End. As noted, the East End was the first place of settlement for many Eastern European Jews. Thus, this congregation would have had particular sympathy for the Romanian Jews, as did Gaster, who was a Romanian Jew, and who received many charity appeals from the community of his origin. Gaster’s relationship with the Eastern European immigrant Jews of the East End came to good use in his finding the best ways to help his Romanian brethren.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 135/81]

The Blaustein (Bluestein) Family and their Relocation from Romania to London:

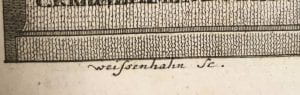

Another Romanian Jewish party helped through Gaster’s efforts is the Blaustein (Bluestein) family. (The surname seems to have been anglicised from Blaustein to Bluestein.) While it would take further research to try to discover the source of the funds Gaster used to help them, and to piece together this family’s full story and the relationship between all the family members, the partial story that emerges from the documents below is worthwhile in and of itself.

Mrs. Ch. Bluestein was a Romanian Jewish widow. One of her sons had a disability. Gaster had helped the family, and now they were established in London. The son with the disability was gainfully employed. Another son, who was to be married, ‘also earns a nice living’. Mrs Bluestein writes to invite the Gasters to the wedding, and to express her gratitude to Moses Gaster.

![Image of Personal Letter of Gratitude to Gaster, Accompanied by a Wedding Invitation (file 131, item 58)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2932-893x1024.jpg)

UCL Special Collections. Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1 [fomerly file 131/58]

I beg to enclose your invite for my son’s wedding. I hope you will come, as you was always a good friend to me when in need so I am happy to let you know of my joy thank God my son is doing a respectable match – and I hope you will live to see joy by your dear children in happiness with your dear wife I am the widow whom you helped to bring over the crippled son from Bucherst, he is grateful to you as he thank God earns £2 – 0 – – weekly – and is quite happy – and my son that is to be married also earns a nice living. We often bless you for everything & I am pleased to tell you of my joy as well as I did my trouble. With best respect, yours gratefully,

Mrs Bluestein

Printed Wedding Invitation Addressed to the Gasters, Sent by Mrs Ch. Bluestein. The Hebrew line at the top is from the prophecy of restoration in Jerimiah 33:11, and is used in the Jewish wedding liturgy: ‘A voice of joy and a voice of gladness, a groom’s voice and a bride’s voice’.

In Summary

Gaster was heavily involved in charity work, on a scale that required communal funding. Although the Board of Guardians of the Poor of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, Gaster’s congregation, provided funding for those beyond their own community, they were too financially limited to finance the full scope of Gaster’s work. Thus, we see that Gaster raised charity funds elsewhere, too. One example of this is Gaster’s ad hoc fundraising network on behalf of Romanian Jewry, which at the turn from the nineteenth to the twentieth century was undergoing strong persecution. We see how Gaster met this challenge, and we see the sweet fruit of his labour.

Blog post by Israel M. Sandman

Close

Close

![[Image and Transcription of Receipt for Donation made by Gaster (file 131, item 44)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2918-1024x652.jpg)

![Image of S. Edelstein’s 21 March 1899 Mostly Hebrew Postcard to Gaster (file 117, item 9)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2919-238x300.jpg)

![[S. Edelstein’s 24 March 1899 Romanian Postcard to Gaster (file 117, item 20)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2920-1024x799.jpg)

![Image of Personal Letter of Gratitude to Gaster, Accompanied by a Wedding Invitation (file 131, item 58)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2932-893x1024.jpg)