The BFE/SCEA: A short illustrated history

By utnvwom, on 16 October 2018

The IOE holds the archive of the British Forces Education Service/Service Children’s Education Association. The BFES/SCE provided education for the children of British Forces personnel initially in Germany, but later worldwide. The Association was established to enable BFES/SCE teachers to keep in touch. The collection contains papers from countries all over the world including Germany, Belize and Hong Kong. With the withdrawal of British troops from Germany over the past few years we have received many new items for the archive. I recently created an exhibition on the history of the organisation for the Assocation’s reunion dinner and thought it would be good to share a short version of it here.

Beginnings

On 9 February 1946 a meeting was called at the War Office where a working party was established to investigate the how to create a Central Education Authority to work under the Control Commission for Germany and Austria. At this point, the question of whether the families of British Service personnel serving in Germany should join them, had not been decided upon. A survey was undertaken by the Chairman of the Working Party, Lieutenant Colonel F J Downs and Mr W A B Hamilton, Assistant Secretary at the Ministry of Education.

The results showed that the total number of children aged between 0 and 15 in these families would be about 6000. The greatest requirement would be for primary education. In June 1946 the Cabinet agreed that families should join serving personnel as long as the education the children received was ‘at least equal to’ that they would have received in the UK. At this point the British Families Education Service was established by the Foreign Office.

Local Education Authorities were asked to co-operate to help recruit teachers to work in the schools in the British Zone of Germany. It was estimated that the number needed would be 200. Two thousand applied and the first teachers arrived in Germany in November 1946. British families started arriving from August 1946 onwards and small informal schools were set up in some areas before official BFES schools opened. The first official BFES schools opened in early 1947.

From issue number one of the BFES Gazette, 6th August 1947. BFE/C/3/1

Expansion

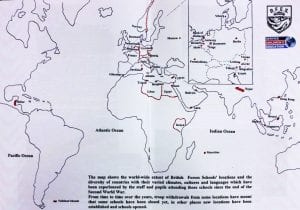

Although the BFES originally provided education for the children of British Forces families in Germany, in the following years BFES/SCE schools were opened in countries across the world including Hong Kong, Cyprus, Malaysia and Mauritius.

The staff of Minden Road School Hong Kong, 1957. BFE/B/5/7

School magazine, and school theatre production programme for Bourne School, Malaysia [then Malaya], c1960. Donated by Janet Methley. BFE/B/6/8

A change of hands

In the winter of 1951-1952 the Service was taken over by the Army and became Service Childrens’ Education Authority (SCEA). In around 1989 a new administration was introduced and in the short-term the organisation was named Service Children’s Schools (SCS) before adopting its current name Service Children Education (SCE).

SCEA Bulletin Number 2, BFE/A/3/1/2

The Association

The BFES Association was founded in 1967 to enable BFES teachers to keep in touch. In the 1980s it merged with the Service Childrens’ Education Association (SCEA), which had changed its name to SCE, to become the BFES/SCE Association.

Map of locations of British Forces Schools in 2007. BFE/A/2/5

The Archive at the UCL Institute of Education

While the collection documents the history of the organisation very effectively, its richness comes from it being mostly collected by teachers who worked for the BFES/SCE. This aspect of the archive gives researchers an insight into the lives of those who were part of an incredible organisation.

The collection comprises:

- Administrative papers of the BFES/SCE Association including minutes of meetings, papers regarding events and publications;

- Recollections, diaries, photographs and school publications of former BFES/SCE teachers working in Belgium, Cyprus, Germany (West Berlin and West Germany), Egypt, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Mauritius, Sri Lanka and Yemen;

- Records of the BFES/SCE itself including teaching resources, information for staff and families living abroad, and publications. Most of these papers have been donated by members of the BFES/SCE Association but relate more generally to the work of the BFES/SCE rather than the work of individual schools.

- A small number of publications issued by the British Forces and community

Researchers can arrange to access the collection at our reading room at the UCL IOE.

ioe.arch-enquiries@ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close

The stories include ‘Battle of Frogs and Mice’, a short animal epic ascribed to Homer in the ancient world and ‘The Three Caskets’ which was used in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. The book also contains a couple of firsts: the first appearance of a Norwegian folk tale ‘The History of Asim and Asgard’ and the first publication of Scott’s poem ‘The Bonnets of Bonny Dundee’ (Hahn, 2015, p. 127). In addition, there are writings by the prolific author of adult and children’s stories Maria Edgeworth (1768 – 1849) who also wrote the well-known education treatise

The stories include ‘Battle of Frogs and Mice’, a short animal epic ascribed to Homer in the ancient world and ‘The Three Caskets’ which was used in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. The book also contains a couple of firsts: the first appearance of a Norwegian folk tale ‘The History of Asim and Asgard’ and the first publication of Scott’s poem ‘The Bonnets of Bonny Dundee’ (Hahn, 2015, p. 127). In addition, there are writings by the prolific author of adult and children’s stories Maria Edgeworth (1768 – 1849) who also wrote the well-known education treatise

Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote: “If we encountered a man of rare intellect, we should ask him what books he read.” At UCL Institute of Education (IOE) Special Collections and Archives we are building a picture of Joseph A. Lauwerys and his life by listing all of the reading material in his personal library. I am one of two volunteers sifting through 28 double-stacked shelves full of books, academic journals, newsletters, meeting proceedings and more collected by Lauwerys, a Belgian-born scientist who became a leader in comparative education studies instrumental in the establishment of the (IOE) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote: “If we encountered a man of rare intellect, we should ask him what books he read.” At UCL Institute of Education (IOE) Special Collections and Archives we are building a picture of Joseph A. Lauwerys and his life by listing all of the reading material in his personal library. I am one of two volunteers sifting through 28 double-stacked shelves full of books, academic journals, newsletters, meeting proceedings and more collected by Lauwerys, a Belgian-born scientist who became a leader in comparative education studies instrumental in the establishment of the (IOE) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). I am Teodora, one of the volunteers listing all of the reading material in Joseph A. Lauwerys’ personal library. I cannot tell which reason influenced me to work with the IOE’s Special Collections and Archives more: my studies in Art History and Material Studies which, by default, bring me closed to any piece of heritage and culture, or my passion for volunteering, which constantly challenges me to step beyond my comfort zone. But I know for sure that the mixture between these two reasons always manages to get me closer to who I want to be.

I am Teodora, one of the volunteers listing all of the reading material in Joseph A. Lauwerys’ personal library. I cannot tell which reason influenced me to work with the IOE’s Special Collections and Archives more: my studies in Art History and Material Studies which, by default, bring me closed to any piece of heritage and culture, or my passion for volunteering, which constantly challenges me to step beyond my comfort zone. But I know for sure that the mixture between these two reasons always manages to get me closer to who I want to be.