UCL’s Student Ephemera collection

By Leah Johnston, on 11 January 2024

Leah Johnston, Cataloguing Archivist (Records), shares details of a newly catalogued collection of student ephemera.

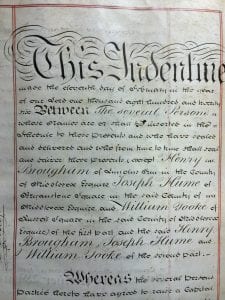

The Student Ephemera collection is a curated collection of manuscripts, publications, artwork, photographs, and objects, relating to the lives of UCL students, the Student Union, and members of UCL staff. The material dates from 1828 to 2002.

The collection was accumulated by UCL alum Dr Mark Curtin and donated to the Student Union, who in turn have deposited the material with UCL College Archives. Over the past year the collection has been fully catalogued and is now all available to view online.

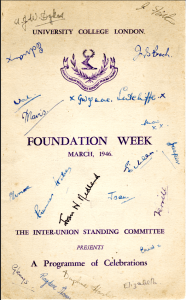

UCLCA/SEC/A/2 Signed Foundation Week programme of celebrations, 1946.

The items within the collection are a representation of student life that complements and expands upon the institutional records held in the College Archive. It consists of a wide range of material, such as correspondence, programmes, tickets, newspaper clippings, leaflets, books, periodicals, photographs, and artwork. The collection also contains a significant number of objects including academic and sporting medals, and both UCL and Student Union branded memorabilia. A small number of items relating to the history of the university are also included, such as correspondence relating to its establishment, centenary publications, commemorative objects, and artwork.

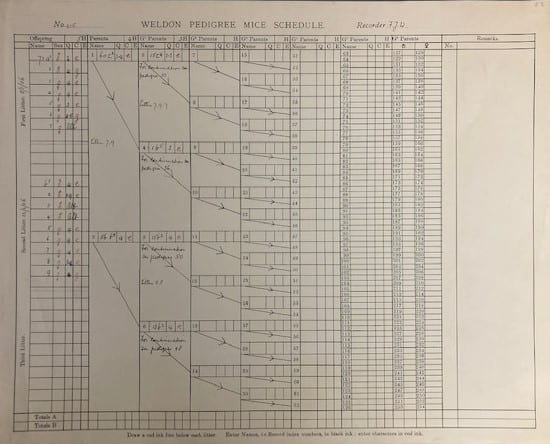

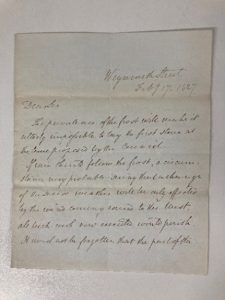

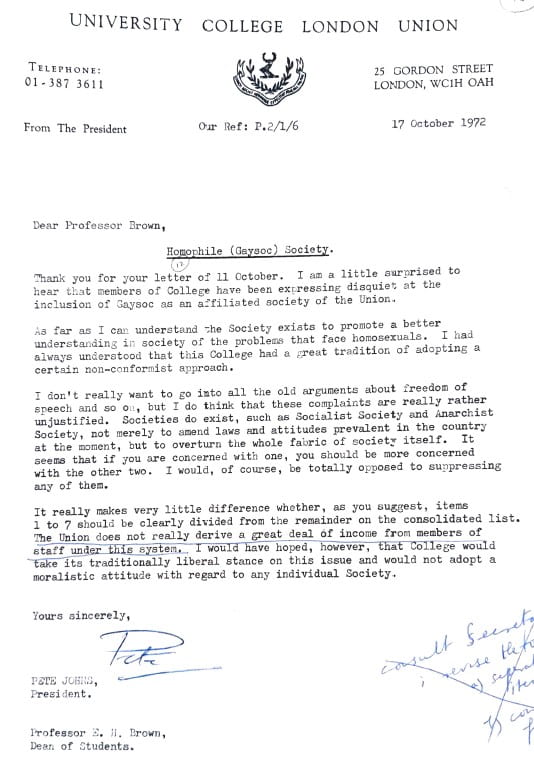

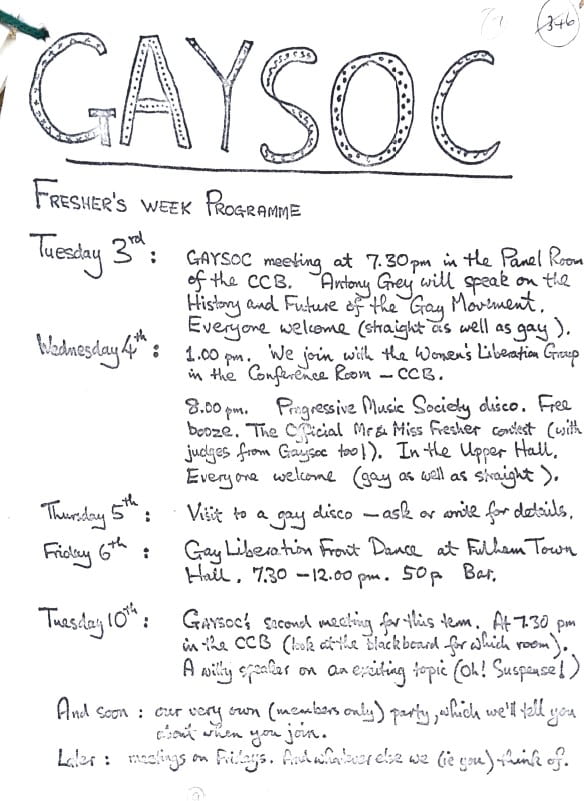

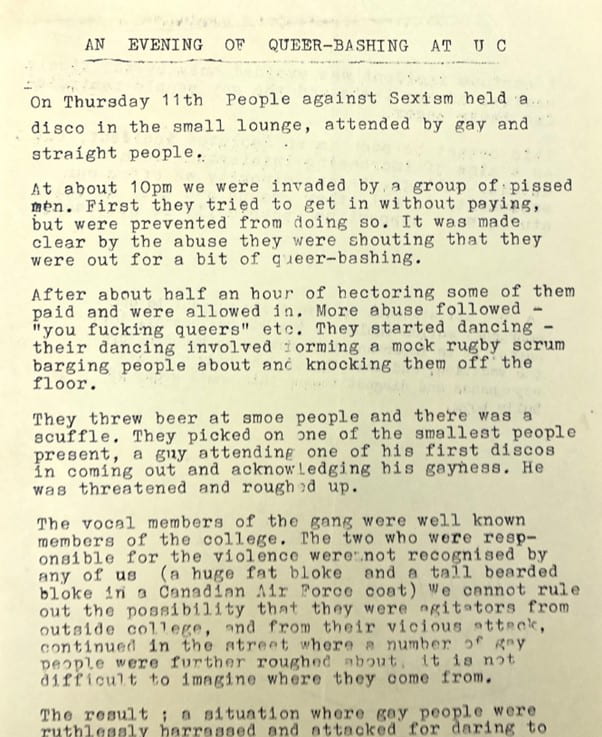

The first series in the collection consists of manuscripts and records and contains items such as correspondence to and from students and staff, theatre and music production programmes, ephemera related to students’ sport, music and social events, newspaper clippings, a medical student’s notebook, and a University College Hospital [UCH] Socialist Society poster.

UCLCA/SEC/A/4: Cutting from ‘Melody Maker’ advertising a Pink Floyd gig at UCL, circa 1969.

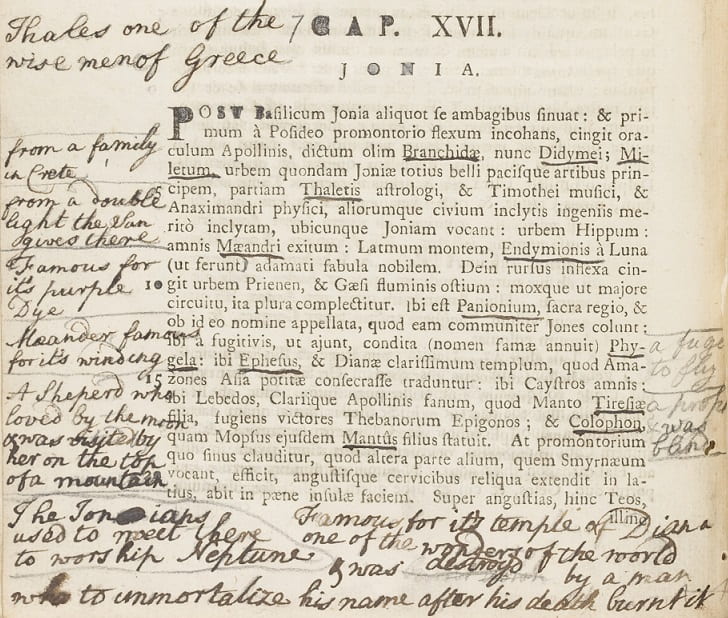

Series two in the collection consists of publications either written by, or related to, past students and staff. There are also a couple of books which relate to the history of the university, along with some university produced publications. A small sub-series of articles taken from Pi Magazine, which were previously framed, are also included.

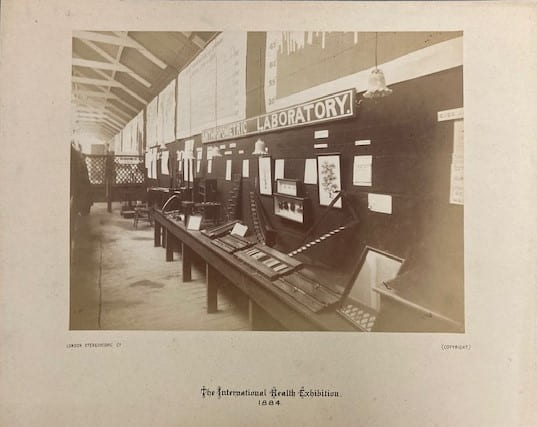

The third series comprises photographs and artwork related to UCL, the Student Union, and UCL students and staff. Included are some of the earliest photographs of the Wilkins building, portraits of Student Union presidents and officers, photographs of sports teams, plus various student association performances and events.

UCLCA/SEC/C/1/21 Photograph of a Dramsoc play on the Portico, c.1947.

The remainder of the collection includes a large series of academic, sporting, commemorative and military medals, and a small series of objects. Included is a Botany Laboratory microscope, a silver cup awarded for first place in the UCH Athletic Club pole jump, a variety of UCL and SU branded memorabilia, such as a car bumper badge, silk tie, union badges and miniature ceramic models. One particularly interesting object in this final series is a Royal Doulton tyg cup which was awarded for first place in the UCH Athletic Club’s ¼ mile handicap race (pictured below). A tyg is a drinking vessel with three or more handles and is traditionally used for sharing a celebratory drink!

Tyg awarded for the UCH ¼ mile handicap race in 1890, and two medals, in the process of being accessioned.

A considerable amount of the collection has formed part of the current Octagon Gallery exhibition, ‘Generation UCL’, which explores the lives of UCL students over two centuries and the foundational part they play to the story of the university. Mounted in the run up to UCL’s bicentenary celebrations in 2026, the exhibition also marks 130 years of Student’s Union UCL.

One of the entrances to the Gen UCL exhibition, on now at the Octagon Gallery.

If you would like to further explore the collection it can now be viewed online at https://archives.ucl.ac.uk/ and by typing ‘Student Ephemera Collection’ into the search bar.

To make an appointment to view the records, or for any queries regarding the collection or the catalogue, please contact us at spec.coll@ucl.ac.uk.

To read more about the Generation UCL exhibition visit the exhibition project page.

Close

Close