To start, I feel this post needs a disclaimer – there is no way I can cover all the inspiring women who have played important roles in the life of the Institute of Education. These are just snapshots, hopefully they will inspire people to look further and read more about these women. I have put them in order of date of birth, in an effort to equalise any hierarchy of perceived significance.

Explanation of abbreviations;

- LDTC – London Day Training College, the name of the IOE on its founding in 1902

- IOE – Institute of Education, the name adopted in 1932

Margaret Punnett (1867-1946)

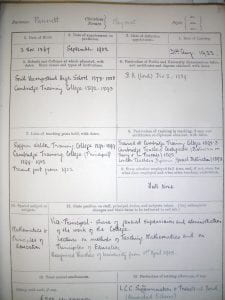

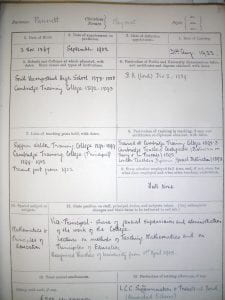

Margaret Punnett’s staff registration page

As Mistress of Method and later Vice Principal at the LDTC, she was responsible for organising and overseeing the teaching of the women students, and had overall responsibility for the teaching of maths, to which scripture and psychology were later added. She lectured also on the Principles of Education.

For many years she carried the main burden of administration, and also took a personal interest in students and their welfare. When she retired the responsibilities of her post were divided, perhaps demonstrating how much work Punnett carried. It is interesting to note that, at a time when women’s salaries were generally lower than those of men with the same level of responsibility her salary on appointment, and subsequently, often equalled that of her male colleagues’.

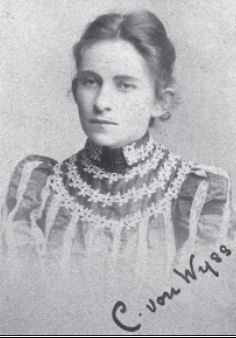

Clotilde Rosalie Regina Von Wyss (1871-1938)

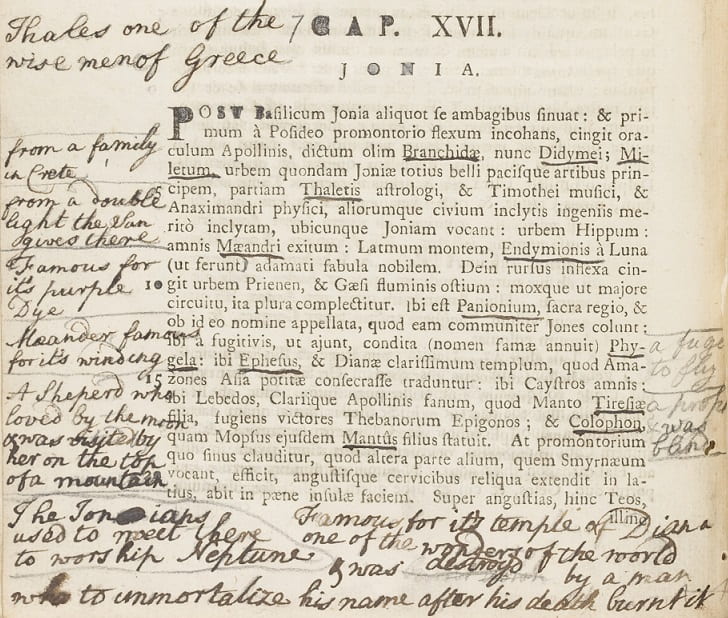

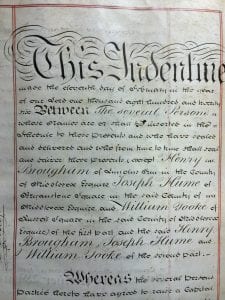

Article by Clotilde von Wyss, IE/12/3/1

Clotilde von Wyss was a pioneer of educational broadcasting and film. Her teaching at the LDTC was enriched by her introduction of collections of plants, an aquarium, artists’ materials and animal photographs. In an article Nature Study for Fidgety Children in the Londinian, the Student Union magazine (Summer 1909), von Wyss expressed her belief in practical manual work as an outlet for children’s natural energy; one example was the creation of gardens in boxes brought in and painted by the pupils. She offered two separate courses in biology at the LDTC, for specialists and non-specialists and, in the 1930s, a special voluntary course for the colonial group. In addition to her work at the college she taught on a voluntary basis at Wormwood Scrubs prison. In retirement she acted as adviser to producers of a film on Wood Ants.

Susan (nee Fairhurst) Isaacs (1885-1948)

Susan Isaacs was an influential child psychologist, her primary interest being in child development. She had had a varied career before joining the Institute of Education, including several years as Head of an experimental school in Cambridge, and was an advocate of nursery education.

Susan Isaacs

At the Institute of Education she was the first Head of the new Department of Child Development. The Department grew rapidly, her work and reputation bringing prestige to the Institute. When the Institute was evacuated to Nottingham in 1939, and the department temporarily closed, Isaacs led the Cambridge Evacuation Survey. Illness prevented her from returning as Head of Department when the Institute moved back to London in 1943 and she was succeeded by one of her earliest students, Dorothy Gardner.

Between 1929 and 1940 Isaacs, under the pseudonym Ursula Wise, was an “agony aunt” replying to readers’ problems in child care journals. She also had her own practice as a psychoanalyst, which she maintained while working at the Institute. Isaacs was awarded the CBE in 1948.

Grace Mary Wacey (1894-1987)

During her 38 years at the LDTC/IOE Grace Wacey saw it grow from a small college chiefly engaged in preparing students to teach in London schools, to a major academic institution with an international reputation. The changes were reflected in the scope and responsibility of her own post: starting off as the only full time member of administrative staff, by the time of her retirement the complement was about 50, over which she, as Secretary, presided.

Grace Wacey

Grace Wacey was remembered as an approachable, kindly yet firm administrator – so much so that in 1984 the IOE organised a party to celebrate her 90th birthday. In 1953 she was awarded the MBE in the Coronation Honours.

Margaret Gladys Calthrop (1886-?)

At the LDTC/IOE Margaret Calthrop taught French and German, lectured in methods of teaching Modern Languages and supervised student teachers’ school practice. She was one of a number of subject tutors who sought to make learning her subject more interesting to children, incurring some opposition from those who wondered whether the essentials of grammar were receiving sufficient attention. Her demonstration lessons attracted a good deal of attention, one on a La Fontaine fable drawing applause from children and students.

In the mid-1930s she suffered health problems. Restored to health she continued to work until she reached retirement age in 1952; she was then offered the possibility of remaining on for a time, but decided not to accept.

Margaret Helen Read (1889-1991)

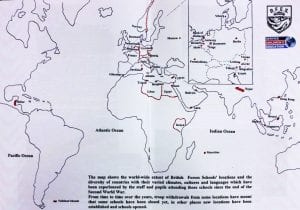

Margaret Read joined the Colonial Department after five years engaged in missionary social work in India. She had carried out research in anthropology at LSE, and been awarded a doctorate. She took charge of the department during the war years and became Head in 1945.

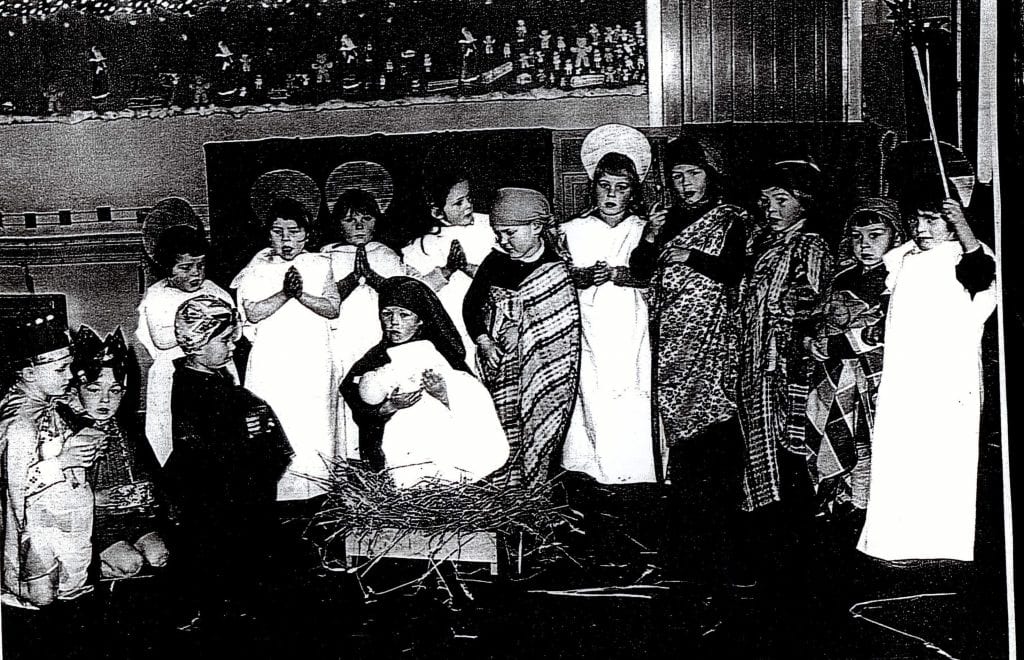

Margaret Read, front row, centre. Class photograph 1946/7

She was a pioneer in applying social anthropology to issues in the developing world, with a particular interest being the nature of cultural change affecting families and individuals who, having for generations practised agriculture in villages, had become part of the industrial proletariat. She thought that education in colonial territories should not be simply in basic skills, but also in citizenship and social relations, taking account of cultural traditions, and she stressed the need for adequate histories of education in each territory, to provide an objective description of what had happened since the earliest European contacts.

Read was a member of, and advisor to, various governmental, and world-wide organisations. In 1948 she was awarded the CBE for work in connection with colonial education.

Marion Elaine Richardson (1892-1946)

As art mistress at Dudley High School Marion Richardson started to develop a child-centred approach to art education, encouraging pupils to use memory and visual imagination in creating art works. At the LDTC she established a specialist course for students training to teach art. She was one of several subject tutors who challenged the prevailing methods of teaching in schools. In addition to her work in schools and the LDTC, Marion Richardson taught classes in Winson Green and Holloway prisons.

Her ideas about child centred art education gained international recognition, while her book Writing and Writing Patterns remained in use in schools for some 50 years. A London school, Senrab Street in Stepney, has been renamed Marion Richardson School in her memory.

Sophia Weitzman (1896-1965)

Weitzman had progressive ideas on methods of teaching history and on the contents of the school curriculum which, she felt, had traditionally been overly concerned with political and constitutional matters. She believed in working from the realities of children’s lives, and saw the value of visits in arousing their interest in history. Weitzman also considered that school should no longer be a forcing house for knowledge, but should prepare children for social living, encouraging initiative and independence.

Her lectures to students on teaching methods spelled out ways in which historical content might be communicated through the medium of active interest, including modelling, drawing, talking, writing and acting of historical plays, historical excursions, films and radio talks.

Like many of her colleagues at the Institute, Weitzman was interested in the educational systems of other countries, and in her later years she devoted much time to work with students who studied Indian education.

Geraldine Susan Maud de Montmorency (1900-1993)

Geraldine de Montmorency’s appointment as the first Librarian of the LDTC was on a part time basis. Realising the restrictions of this, with the help of students from UCL’s School of Librarianship, she worked on cataloguing and on a classification scheme within the subjects. Additions to the stock came from donations of books and material, as well as purchases.

Over the years de Montmorency increased the number of days she spent at the Institute, in 1940 her post was made full time. Both before and after the second world war specialist collections were developed, e.g. in the fields of colonial education, child development, comparative education and English as a foreign language. Although the marriage bar had been lifted some years earlier, the expectation that women could not cope with working and managing home life prevailed, and de Montmorency retired her post at the IOE upon marriage in 1957. By the time Geraldine de Montmorency resigned her post, the Institute Library had grown massively, with a stock over 50,000 volumes, and had achieved an international reputation.

Dorothy Ellen Marion Gardner (1900-1972)

Dorothy Gardner trained as a Froebel teacher, then worked with young children in a variety of settings and as a trainer of teachers and nursery nurses before becoming a part time student on the new advanced Child Development course at the IOE, while lecturing at Bishop Otter College. As a student she greatly admired Susan Isaacs, the first Head of the new Department of Child Development, and in due course succeeded her.

Gardner became head of the Department of Child Development in 1943. When teaching – which included a course on the needs of young children in war time – resumed in January 1944 it had to take place in the evenings because teachers were unable to get paid leave. In 1948 Gardner established a research centre at Coram Fields: one of its projects, conducted jointly with the Institute of Child Health, was a long term study of local children.

Gardner played an important part in shaping the development of child centred education. A highly regarded community nursery centre in West London, catering for 100 children, bears her name.

A number of these women recount their experiences in the volume Studies and Impressions, 1902-1952 Harrison, A. S., and University of London. [edited by A. S. Harrison … Et Al.]. London: Evans Brothers for the U of London Institute of Education, 1952. Print. https://ucl-new-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/5qfvbu/UCL_LMS_DS21167882720004761

Further biographical information has been collated from the Institute archives. Extended profiles of most of these women are available on request from the IOE archives ioe.arch-enquiries@ucl.ac.uk

If you have any ideas of who could be included in this list, and why they should be here, please add them in the comments.

Close

Close