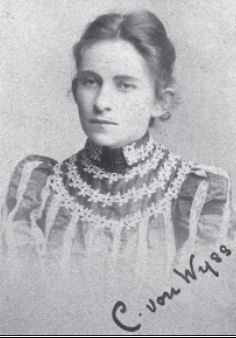

An eminent female academic at the IOE: Clotilde von Wyss (1871-1938)

By Nazlin Bhimani, on 10 August 2018

In my research on teacher training at the London Day Training College (LDTC), which became the Institute of Education (IOE) in 1932, I have found the relatively unknown Clotilde von Wyss to be one of the most intriguing female teacher trainers.[1] Von Wyss taught at the LDTC and IOE from 1903 to 1936. This post provides a brief overview of her contributions to teacher training in the interwar era.

As was typical in the late 19th century to the first half of the 20th century, most women became qualified teachers to have professional careers, and many women remained unmarried to retain their independence. Some women teachers progressed in their careers by taking up headships and others, mainly the ‘intellectually gifted women’ from the middle classes, went into teaching in higher education.[2] Von Wyss followed this latter path and trained as a teacher at Maria Grey College, Brondesbury and gained a distinction in her Cambridge Teachers’ Certificate. Before her appointment at the London Day Training College (LDTC), von Wyss taught at various schools including St. George’s High School in Edinburgh from 1894 to 1897. During this time, she was also an external student at the Heriot-Watt College where she took classes with the distinguished naturalist Sir Arthur Thomson.

Clotilde von Wyss (1871-1938)

From 1897 to 1900 she taught biology at her old school, North London Collegiate, after which she took up a lectureship at the Cambridge Training College. In 1903, she began to work on a part-time basis at the London Day Training College (LDTC) where she taught biology, hygiene, nature study, art and handicraft. Von Wyss was soon appointed as a full-time member of staff supporting the Mistress of Method and Vice-Principal, Margaret Punnett (another eminent female academic), with the welfare of the women students.[3]

Von Wyss’s pedagogical contributions are significant. The 1929 issue of the student magazine, The Londinian, reviews the annual biological exhibition which von Wyss organised and provides evidence of novel teaching methods including the use of visual illustrations, objects, story-telling and peer-learning to communicate complex concepts. Her students presented these concepts to other students using the items on display, which included a dissected cat, the digestive organs of a rabbit, and a frog which was used to detect a heartbeat. There was also a section where the students learnt about amoeba and another which focused on genetics or the ‘principles of heredity’ and the role played by chromosomes:

Miss Gascoyne … was demonstrating the principles of heredity by means of charts…[and the] story of the black gentleman cat who married a sandy lady cat was touching in the extreme. How he longed for his little boys to be tortoiseshell, something like him and his dear wife! But they never could. That distinction was confined to the girls of the family. And all because of a wretched chromosome with a hook in it![4]

She was a progressive educationalist and expected trainee teachers to demonstrate aspects of child-centred learning in their teaching practice. Her written comments on her observations of student teachers’ classroom teaching practice are held in the IOE’s archive. They describe her child-centred approach and what she believed to be the essential qualities of a teacher and ‘good’ teaching. Of utmost importance, for her, was that teachers understand the world of the child so that they could see things from the child’s perspective. Teaching children to observe would, she emphasised, enable the child to ‘come alive’.[5] She was critical of students who simply derived teaching material from textbooks and imparted it mechanically.

Von Wyss was known outside of the LDTC and IOE. Her lessons for the BBC’s Broadcasts to Schools in the late 1920s made a profound influence on science teachers throughout the country. In the 1930s, ‘her ants’, which she had nurtured for the students to observe, were featured in the documentary film ‘Wood Ant’ as two letters from the mid-1930s confirm. She made arrangements to show the documentary at the Autumn meeting of the School Nature Study Union at County Hall and later to the students at the LDTC.[6]

Von Wyss had also established herself as a formidable naturalist. This was recognised by teachers and by the officials at the London County Council. Many teachers used her biology and nature studies textbooks which contain her own illustrations, and as a member of the textbook selection Committee at the London County Council Committee, she assessed nature study and hygiene courses at other teaching colleges.[7] As editor of the School Nature Study Journal, she was known for highlighting the educational benefits of nature study, providing a course outline for the subject, and sharing the most effective teaching methods. In this, she had the backing of such influential people as L.C. Miall who was a Professor of biology at a Yorkshire College (later part of the University of Leeds), J. Arthur Thompson, the renowned naturalist under whom von Wyss studied in Edinburgh, the writer H. G. Wells, C. W. Kimmins who was the Chief Inspector of the London County Council, and Sir Percy Nunn who was director of the LDTC and IOE during von Wyss’s tenure. (Nunn was also involved in the Nature Study movement for he chaired the Union from 1905 to 1910).[8] They were all eugenicists, as was von Wyss.

Her contributions to the study of science were acknowledged publicly when, in 1914, she was appointed Fellow of the prestigious Linnean Society. [9] Her obituary in Nature describes her as a ‘brilliant and inspiring teacher’ whose students ‘went out to teach with a feeling of power and confidence’ and ‘teachers of many years standing still remember her with affection and gratitude’. She ‘never lost sight of the interdependences of theory and practice’ and ‘like all true teachers, she was also continually a learner’. [10]

REFERENCES

[1] Apart from E. W. Jenkins’ work on The Nature Study Movement(1981) in which he introduces von Wyss’ contributions to nature study and Richard Aldrich’s biographical introduction to her in the Centenary History of the Institute of Education(2002), there is little on von Wyss’ pedagogical innovations.

[2] Fernanda Perrone, ‘Women Academics in England, 1870–1930’, History of Universities12 (1993): 339, 347.

[3] Richard Aldrich, ‘The Training of Teachers and Educational Studies: The London Day Training College, 1902–1932’, Paedagogica Historica40, no. 5–6 (October 2004): 624.

[4] ‘Harold’, ‘The Biological Exhibition’, The Londinian, no. Summer (1929): 15.

[5] Correspondence with Gaumont-British Instructional Ltd dated 20th March (1935?) and 7th October 1935. ‘Von Wyss Staff Records (1909-1949)’.

[6] Diploma Report dated 29/05/22. In: Clotilde von Wyss, ‘Diploma Reports 1922 Women Students’ (London Day Training College, 1922), IE/STU/A/7, UCL Institute of Education Archives.

[7] British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Notes on the Courses: Nature Study with Clotilde von Wyss’, in Broadcast to Schools (January to June 1929)(London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1929), 17.

[8] E. W. Jenkins, ‘Science, Sentimentalism or Social Control? The Nature Study Movement in England and Wales, 1899‐1914’, History of Education10, no. 1 (March 1981): 39.

[9] ‘Societies’, The Athenaeum, no. 4542 (14 November 1914): 512.

[10] R. F. S., ‘Obituary: Miss Clotilde von Wyss’, Nature142 (26 November 1938): 944–45.

Close

Close