Special Collections content in new online collection: Pandemics, Society and Public Health 1517-1925

By Joanna C Baines, on 11 April 2024

Posted on behalf of Caroline Kimbell, Head of Commercial Digitisation:

In the aftermath of the Covid 19 pandemic, UCL has contributed around 12,000 images of rare books and original documents from our Special Collections to a prestigious new online teaching resource from British Online Archives: Pandemics, Society and Public Health 1517-1925 launched this month (April 2024).

UCL content from 6 named Special Collections, the School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies (SSEES), rare books from Stores, and the archive of Edwin Chadwick forms around a quarter of the new resource, alongside records from the National Archives, the British Library and London Metropolitan Archives.

Women wearing surgical masks during the influenza pandemic of 1919, Brisbane.

State Library Queensland

Spurred by an all-too-understandable upsurge in research interest in pandemic history, the project focuses on primary sources relating to outbreaks of 4 diseases in British history – plague, cholera, smallpox and influenza. The academic call-to-arms for the project is summed up by editorial advisor Emeritus Professor Frank M Snowden of Yale: “Epidemic diseases are not random events that afflict societies capriciously and without warning… To study them is to understand [a] society’s structure, its standard of living and its political priorities”.

The online resource starts with documents relating to the first state-mandated quarantine in England, in 1517, but the earliest UCL items in the collection is a 1559 edition of William Bullein’s A newe boke of phisicke called ye gouernment of health. The project ends with the Spanish Flu epidemic which followed the First World War, on which UCL contributes a Ministry of Health Report on the pandemic of influenza 1918-1919 and a 1920 typescript Report on mortality among industrial workers, in relation to the influenza epidemic. UCL sources reflect the university’s preeminent focus on medical history, the development and application of vaccinations, and UCL sources are strong in campaigning, statistical and investigative works. Named Special Collections included in the selection include the Hume and Lansdowne Tracts, London History, Mocatta and Ogden collections, and material from our Medical History, Rare Books and SSEES collections are also included.

The main UCL archive represented is that of Edwin Chadwick (1800-1890), who began his career as secretary to UCL spritual founder Jeremy Bentham and was a lifelong campaigner for public health. He believed strongly that poverty was often the result of poor health, and poor health in turn was the result of poor living and working conditions, in particular sanitation. His lifelong campaigns, many focused on cholera, resulted in the passing of the first Public Health Act in 1848 and the establishment of the Board of Health, which he chaired until 1854. This digitisation programme includes selected reports, memos, statistics and 120 letters from his collection, with correspondents including Florence Nightingale, Lord Palmerstone and agriculturalist Philip Pusey.

The online collection is available now, and UCL library members will have access to the entire collection, which groups source materials into five themes: economics and disease, control measures, international relations, medicine and vaccination and public responses.

If you are a member of UCL Libraries, the new resource can be accessed by visiting our online Databases page and searching for ‘British Online Archives’.

A look at two books from UCL’s James Joyce Book Collection

By Sarah Pipkin, on 5 April 2024

Post by Daniel Dickins.

The James Joyce Book Collection is a collection of rare books and archival materials in UCL Special Collections. Originally established as part of the James Joyce Centre in 1973 with the help of the Trustees of the Joyce Estate, Faber & Faber, and the Society of Authors, it is the only significant research collection on James Joyce in the UK. Containing around 1400 items, the collection includes multiple editions of all Joyce’s major works (including first editions and translations), alongside criticism and contextual literature. In addition, the collection includes material relating to Joyce’s patron, Harriet Shaw Weaver, and to his daughter, Lucia Joyce.

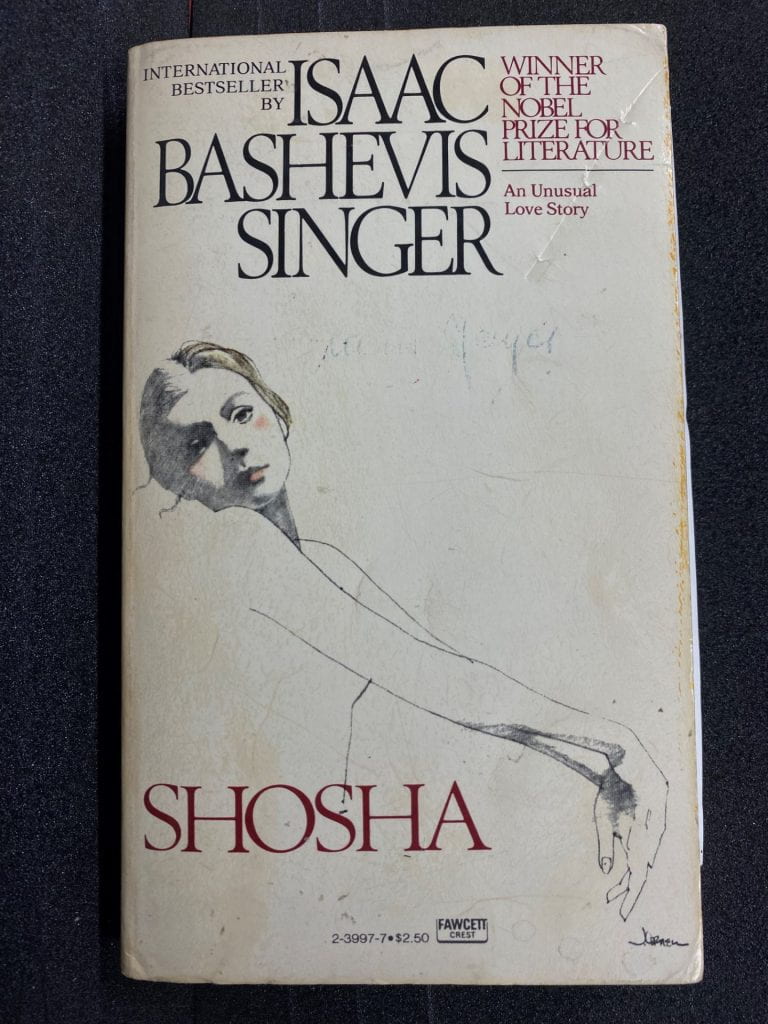

Title page of Shosha by Isaac Bashevis Singer (1978)

One item in the collection is a copy of Shosha by Isaac Bashevis Singer. We have a good indication that this book was owned by Lucia Joyce: ‘Miss Joyce’ is written in pen on the front cover and in pencil on the inside cover, and there is another pencilled writing that states, ‘Lucia Joyce Bequest’. There is also a note inside the book confirming that it arrived with ‘the Lucia Joyce papers from St Andrew’s Hospital’, which is the last hospital in which Lucia was institutionalised. This book was printed in 1978, so Lucia would have been at least 71 years old when she purchased this book. This book is useful for research into the later years of Lucia Joyce’s life, but there are many other reasons why the book is worth preserving. It won the Nobel Prize for literature so was considered significant at the time; it can be placed alongside items in UCL’s Hebrew and Jewish collection for research into 20th century Jewish writing; or it can be considered as an example of a 1970s paperback, or as a book owned by someone in a hospital.

Title page of Irish Short Stories by Seamus O’Kelly (1960s – exact publication date is unknown)

Another item in the Joyce collection is Irish Short Stories by Seamus O’Kelly. O’Kelly was a contemporary of James Joyce; there is no publication date for this book, but the stories were originally written before O’Kelly’s death in 1918. This item therefore contributes to a collection that expands beyond Joyce to look at Irish literature of the early 20th century. This book was also donated by Jane Lidderdale so it may have been owned by Lucia Joyce, but there are no annotations confirming this so further investigation is needed to determine more details of its provenance. There are, however, two pencil drawings near the back of the book. One is of a plant, and the other is a landscape scene labelled ‘Knocknarea’, in Ireland. If Lucia owned this book, she could be the source of these drawings – as well as being a professional dancer, she was also an artist who produced cover art for at least one James Joyce book.

Last page of Irish Short Stories, with a pencilled drawing of Knocknarea

With the Joyce collection, we can learn about James Joyce himself, but we can also research his daughter, his contemporaries, and 20th century literature more broadly, allowing us to paint a fuller picture of the worlds surrounding him. The Joyce collection is fully catalogued and is open to the public. To learn more, see our online guide and to browse the collection’s contents, search for JOYCE on Explore.

Daniel Dickins was seconded to UCL Special Collections as Outreach and Exhibitions Coordinator in 2024. When not supporting Special Collections, he works in UCL’s Science Library.

Applications for the 2024 Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize are now open!

By Ching Laam Mok, on 26 March 2024

Applications of the Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize open from 25 March to 5 May 2024.

The Anthony Davis Book Prize is open to any student studying at a London-based university who has a coherent collection of printed and/or manuscript material. The winner will receive £600 as well as an allowance of £300 to purchase an item for UCL Special Collections. The prize will also include the opportunity to give a talk on your collection as part of the UCL Special Collections events programme.

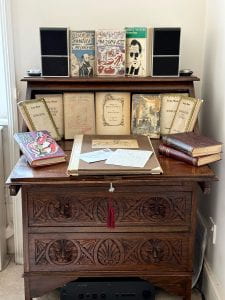

Items from the last year winner Emma Treleaven’s collection on making dress and textiles before 1975.

The collection should be based around a common theme which has been deliberately assembled and that the collector intends to continue growing. The items in your collection do not have to be typically seen as valuable or historically important. If you collect printed or manuscript materials, which can include anything from comic books and postcards to modern publications, then you are welcome to apply!

Items from the collection of 2022 winner Hannah Swan.

The prize is intended to encourage students to collect books, printed items, and manuscript material, by recognising a collection formed by a London student at an early stage in their collecting career. All current undergraduates and postgraduates studying for a degree at a London-based University, both part-time and full-time, are eligible to enter for the prize.

Books from Daniel Haynes’ collection, the 2021 winner.

This year, we have changed the application process. We are no longer asking applicants to email us – instead, please apply by filling out our online form here.

The application period will end at 23:59 on Sunday 5th May 2024. Shortlisted applicants will be invited to present their collections to a panel with representatives from UCL Special Collections, the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association, and the Bibliographical Society. This will take place on 5th June 2024, between 10am and 1pm.

We look forward to seeing your book collection!

Books from Alexandra Plane’s 2020 winning collection.

More information:

To apply or to learn more about the eligibility criteria:

For advice on what a collection can look like:

- How to be a student book collector (and apply for the Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize)

- Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize: Collecting with Intention

- Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize: Interview with LSE Library

Conversations with previous winners and finalists:

- Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize: Books that built a zoo

- Bound to read: collecting Victorian texts in 20th-century bindings from Bookish: The Birkbeck Library Blog

- Q&A with Erick Jackaman, 2021 Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize Runner Up

- Florilegium: gathering the language of flowers from Bookish: The Birkbeck Library Blog

Announcements of previous winners:

- Winners of the 2023 Anthony Davis Student Book Collecting Prize

- Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize 2022: results announced

- Announcing the winners of the 2021 Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize

- Results announced for Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize 2020

Keep an eye out on the blog for an interview with last year’s winner!

Kelmscott School historians research natural history with UCL Special Collections

By Anna R Fineman, on 20 February 2024

Photo of Kelmscott School pupils sitting in the Culture Lab at UCL East. Rare books they are about to explore are displayed on a table in the foreground.

Last term the Outreach team of UCL Special Collections were delighted to collaborate with Year 9 History enthusiasts at Kelmscott School in Waltham Forest. The club, called Becoming an Historian, took place over six weekly after-school sessions at Kelmscott School. The 18 students defined the skills and qualities which make a good historian, learnt how to undertake historical research of primary resources, and each explored an item from UCL Special Collections in-depth. They chose Natural History as their theme and enjoyed investigating historical beekeeping, beautiful marine watercolours and whether plants have feelings. The students learnt to communicate their research in different ways for different audiences. Here they have produced informative and engaging museum labels to create a digital exhibition. You can also read their personal responses to the collection items on X (previously Twitter).

The students concluded their project by coming to visit UCL East and really enjoyed seeing the original Special Collections items they had been researching, in the Culture Lab:

It was great to see the book that I’ve been working on, it was really rewarding

It was interesting to see the source in person. There were a lot of things you do not catch when using an online version.

It felt really cool looking at something created almost 100 years ago!

UCL Special Collections say a huge thank you to the students for undertaking this research and for helping to tell the stories of these extraordinary rare books and archives in our care.

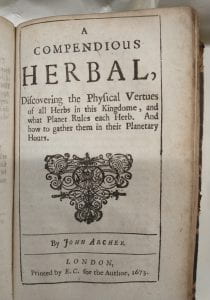

Every Man His Own Doctor (1673) by John Archer

The title page for part two of John Archer’s 1673 herbal Every Man His Own Doctor.

This rare book was written in 1673 by a man named John Archer (1660 – 1684), a King’s chemical physician who believed that every person should know about what they put into their bodies and the effects this might have. The book includes home remedies and cures to treat and prevent pox, gout, dropsy and scurvy. It also includes ways of calming your mind, exercising, sleep and the uses of tobacco.

Lukas

‘Every Man His Own Doctor’ by John Archer is a book that focuses on herbal medicine. It provides information on various plants and their benefits. The book is implying that people should take serious care of their health. It’s great for those who are interested in exploring different treatments and is useful for those who want to learn more about healthcare.

Madeeha

‘Every Man His Own Doctor’ was written by John Archer. He published the book in 1673, written in English. The book is about diet, herbs and medicine in the 1600s. The book provides detailed information on the properties and uses of numerous herbs. It also includes advice on maintaining a healthy life. The book aims for people to take control of their lifestyle and to benefit from natural remedies.

Noor

Original hand painted artwork by Marian Ray for her filmstrip Seeds (1940s – 1980s)

Artwork by Marian Ray c.1940s – 1980s, for her educational film Seeds

Marian Ray was a successful business owner who began work in the 1940s producing filmstrips for schools. She worked at the BBC during World War Two as an animation artist. She would study seed growing as a source of material, and produced film artwork and a booklet covering: the evolution of seeds and how they grow and live; the nutrients they need; different types and shapes of seed; the animals that love to eat the seeds.

Ayub

The archive of Marian Ray contains artwork and a booklet on seeds. It contains in-depth information about seeds, how they work and different types. It is also about the evolution of seeds, how they grown and live. There are numerous diagrams that show different seeds and parts of seeds.

Raqeeb

Remarks on Rural Scenery by John Thomas Smith (1797)

An illustration of Hackney looking extremely peaceful from John Thomas Smith’s 1797 book Remarks on Rural Scenery.

Remarks on Rural Scenery was published by John Thomas Smith, a painter and engraver, in 1797. It shows engravings of rural areas of London in the 18th century; however, these areas are not so rural today. Westminster is depicted as a vast, green area, Hackney a quiet village, Deptford a woodland area with a large cottage. This book is a good way to see what life was like during the 1700s, and to see just how much the world we live in has changed since then. It can help us to discover more about human life and geography through images before the invention of the photograph.

Anton

Marine Sketches from Nature by Edward Duncan (c.1840s – 1880s)

A page from Edward Duncan’s sketchbook Marine Sketches from Nature, featuring a drawing of seagulls swooping in the air and a watercolour landscape of the sea with distant land mass and a golden sky (1840s – 1880s)

In the Victorian era Edward Duncan, a famous British artist, published his sketchbook of marine paintings. The sketchbook, dating from 1840s – 1880s contains watercolour paintings of the sea, boats and landscapes. Duncan was born on 21 October 1803 and died on 11 April 1882 aged 78. He made two sketchbooks – Marine Scraps and Marine Sketches – filled with beautiful watercolour sunsets and oceans. Some of his paintings were called The Shipwreck, The Lifeboat and Oysters.

The sketchbooks are part of Egon Sharpe’s Collection and were donated to UCL Special Collections. Now everyone can benefit from his beautiful sketches.

Amelie

During the Victorian era a series of sketchbooks dating from 1840 – 1880s were made by a British Man called Edward Duncan. He lived from 21 October 1803 to 11 April 1882. These sketchbooks are called Marine Sketches from Nature and Marine Scraps. They contain various sketches and watercolour paintings of marine harbours, animals, landscapes and nature.

Edward Duncan married a woman called Bethia Higgins. The auction of some of his stunning works three years after his passing, took just three days, which showed how sought after his work was.

Kitty

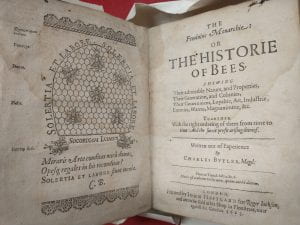

The Feminine Monarchie or The Historie of Bees by Charles Butler (1623)

The title page double spread of Charles Butler’s The Feminine Monarchie or The Historie of Bees (1623).

The Feminine Monarchy or the History of Bees is a beekeeping guide that was made by Charles Butler. This guide was used for over 250 years, before people developed moveable comb hives. Charles’ book has ten chapters from swarm catching to the benefits of bees to fruit (pollination). This 1609 science treatise is considered the first book on the science of beekeeping and was translated into Latin in 1678.

Iris

The Feminine Monarchy was made by Charles Butler. He was born in 1571 and passed in 1647. He observed that bees produce wax. He also learned that wax is produced from their own body. He was among the first to assert that the leader was a ‘woman’ aka the queen bee. The Feminine Monarchy was originally published by Joseph Barnes, Oxford in 1609. The book was later translated into Latin.

Diana

The Feminine Monarchy is a guide ‘written out of experience’ by Charles Butler. It is a 1609 science treatise and is considered the first work on the science of beekeeping. Its 10 chapters on bees, which have been used for 250+ years, detail the following: bee gardens; hive-making materials; swarm catching; enemies of bees; feeding bees; and the benefits of bees to fruit (pollination). It has been translated into Latin.

Mariam

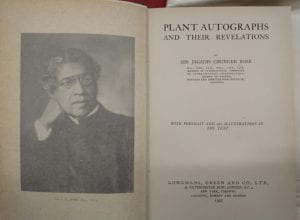

Plant Autographs and their Revelations by Jagadish Chandra Bose (1927)

The title pages of Jagadish Chandra Bose’s Plant Autographs and Their Revelations (1927)

This book is about a series of studies on whether plants have feelings and thoughts. One particular tree in Faridpur, Bangladesh, was struck by lighting and now bends at a 60 degree angle. Until it doesn’t… During the morning the ‘neck’ of this tree (Phoenix sylvestris) points upwards. However, during the evening, the tree bows downwards to look like it was praying, which is how this tree earns its name The Praying Palm. ‘Pilgrims were attracted in large numbers. Offerings were made to the tree which had been ‘the means of effecting marvellous cures.’

James

Plant Autographs and Their Revelations is a book about a series of studies that indicate whether plants have feelings or not. There is one tree in the book called the Praying Palm of Faridpur. This tree was a date palm (Phoenix sylvestris). They call it the Praying Palm because in the morning the tree points upwards and in the afternoon it bows downwards. This looked as if it was praying. Pilgrims were attracted in large numbers. Offerings were made for the tree for alleged faith cures. These trees can be found in Bangladesh or Bengal.

Kristian

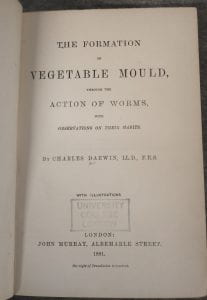

The title page of Charles Darwin’s 1881 book The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Actions of Worms: with observations on their habits

This is an 1881 book by Charles Darwin on earthworms. It was his last scientific book and was published shortly before he passed away. The first edition went to press on 1st May, and it was remarkably successful , selling 6000 copies within a year, and 13,000 before the end of the century.

Gabriel

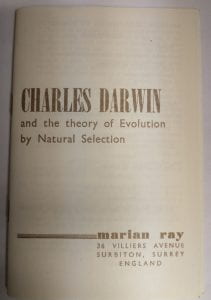

A booklet titled Charles Darwin and the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection by Marian Ray, to accompany her hand illustrated educational film (c.1940s – 1980s)

We learnt about Marian Ray, a successful businesswoman who was born in 1923 and died in 1999. She created educational film strips for schools, mostly homemade. She translated and sold them to more than 70 countries. She worked in the audio-visual era in World War Two. Her earliest film strips were in black and white and called ‘Cotton’ and ‘Evolution of the Horse.’ One film she made was about Charles Darwin.

Amir

Marian Ray was born in 1923 and died in 1999. She was a successful businesswoman and she made educational film strips for schools. They were homemade and were translated for more than 70 countries. In World War Two she worked in the audio-visual era. Her earliest film strip, black and white, was named ‘Evolution of the Horse.’ She made depictions of Charles Darwin’s observations of horses.

Ismael

UCL’s Student Magazines

By Colin Penman, on 14 February 2024

On a recent (well, November) trip to the USA to see family, I managed to visit ‘All That’s Fit for Student Print’, a fascinating exhibition of student publications at Binghamton University Special Collections, and meet University Archivist Maggie McNeely and her colleagues – should you happen to find yourself in the Southern Tier of New York State, pop in! So, for this ‘UCL birthday’ post, I thought I might highlight our own student publications.

Our student magazines are part of College Collection. This is an unwieldy agglomeration of over 5,000 items related to the history of UCL, and includes monographs, periodicals, ephemera (tickets, programmes, invitations and more), and official publications, such as Calendars and Annual Reports, dating from before UCL’s foundation on 11 February 1826 up to the present day. There are also published lectures, examination papers, prospectuses, and works on the Bloomsbury area of London, as well as the other institutions which form part of the wider University of London.

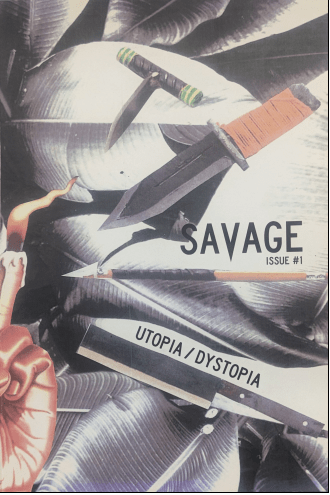

Magazines in general, and student-focused ones in particular, tend to have a short active life, and are little regarded. You read it, you bin it, you move on – ephemeral indeed. But it’s their transitory quality that gives them such a fascinating afterlife, even in the gaps and silences (there’s usually a reason why we don’t have something), because you get a real snapshot of student life and preoccupations at a specific point in time. And let’s not forget the aesthetic aspect. I love the jaggy design on the cover of Savage (2015 – the only issue we have so far), which fairly hurts the eye:

And you don’t need to be told the dates of these numbers of Pollardian and Torque – everything about them says: it’s the 70s, and nothing but the 70s.

The earliest student magazine that we have is the London University Chronicle, from 1830 – before UCL was UCL – but the main student organ remains Pi, founded in February 1946, and named for the Provost of the time, David Pye. There was a strong feeling that, following the trauma of the war, an effort needed to be made to bring together what was now a highly disparate group of 2,100 individuals (‘the largest single college in the British Empire’) who had been scattered abroad in the armed forces or evacuated with their departments to various parts of England and Wales. There are some echoes there of the shock of Covid – a large body of students with little or no experience of a real, in-person Bloomsbury community.

Pi was always a campaigning paper, or at least offered a platform to student campaigners, as we can see in these examples from the 1970s and 1980s. In November 1979, the front cover shows a man climbing over security gates, which had just been installed following a series of robberies and sexual assaults – and some fierce student campaigning:

Pi 382, 2 Nov 1979

And wider politics make their presence felt in arguments over student unions as a closed shop, and the relevance of the Miners’ Strike to student life (October 1984):

Pi 453, 1 Oct 1984

Pi 404, 4 Oct 1982, p. 4

As a semi-official voice of the Union, Pi has always reflected student politics and local concerns, such as direct action to get pedestrian crossings installed around campus, and our old favourite, refectory food (price and quality!), but also student involvement in the politics of the wider world, for example the fate of students caught up in the unrest of Eastern Europe, and campaigning on apartheid.

Of course Pi has its more frivolous side, with its fair share of ‘Miss Fresher’ contests or burning questions such as ‘Should College dances have chaperones?’ (yes, really), pop star interviews, and Rag shenanigans (you can find a couple of dedicated rag mags elsewhere in College Collection).

There were other ‘mainstream’ publications before Pi, such as the Union Magazine (1904-1919), University College Magazine (1919-1939), and New Phineas (1939-1956). But for the unexpected, and to get a picture of sometimes niche preoccupations and interests, it’s the smaller-scale efforts that shine. Sportophyte, a magazine of ‘botanical `humour’, was founded in 1910 by none other than Marie Stopes. (College Collection also contains copies of Stopes’s Married Love and, unfortunately, her poetry.) Crosswords and Maranatha are Christian publications, and we have one copy of Not the Pakistan Society Magazine:

There are of course party-political publications, most of them fairly short lived, for example Red Dwarf (Labour Club), Blue Dwarf and Tory (Conservatives), and Red Giant (Socialist Society), and departmental ones, which can provide unique information about local goings-on and personalities. I’m a fan of the Library School publication The Crazy World of Arthur Brown (1970), which manages to link the singer of the psychedelic classic ‘Fire’ with Professor Arthur Brown, Director of the Library School and Professor of English:

We love to use this kind of material in our teaching and outreach activities, and you can of course visit us to consult them yourself – a shelfmark search for COLLEGE COLLECTION PERIODICALS on our library catalogue, Explore, will bring up most of the titles, though we are still finding more. And of course many titles have been digitised: see the History of UCL page of our Digital Collections. You can also see many titles in our current exhibition Generation UCL: 200 Years of Student Life in London, in the UCL Octagon until August this year:

We are also very keen to close the many gaps that exist in the collection, so I want to end here with an appeal to anyone who thinks they might have something that’s missing from our current holdings, and might be willing to part with it, to get in touch with us. We’d love to hear from you!

UCL’s Student Ephemera collection

By Leah Johnston, on 11 January 2024

Leah Johnston, Cataloguing Archivist (Records), shares details of a newly catalogued collection of student ephemera.

The Student Ephemera collection is a curated collection of manuscripts, publications, artwork, photographs, and objects, relating to the lives of UCL students, the Student Union, and members of UCL staff. The material dates from 1828 to 2002.

The collection was accumulated by UCL alum Dr Mark Curtin and donated to the Student Union, who in turn have deposited the material with UCL College Archives. Over the past year the collection has been fully catalogued and is now all available to view online.

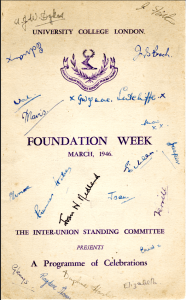

SEC/A/2 Signed Foundation Week programme of celebrations, 1946.

The items within the collection are a representation of student life that complements and expands upon the institutional records held in the College Archive. It consists of a wide range of material, such as correspondence, programmes, tickets, newspaper clippings, leaflets, books, periodicals, photographs, and artwork. The collection also contains a significant number of objects including academic and sporting medals, and both UCL and Student Union branded memorabilia. A small number of items relating to the history of the university are also included, such as correspondence relating to its establishment, centenary publications, commemorative objects, and artwork.

The first series in the collection consists of manuscripts and records and contains items such as correspondence to and from students and staff, theatre and music production programmes, ephemera related to students’ sport, music and social events, newspaper clippings, a medical student’s notebook, and a University College Hospital [UCH] Socialist Society poster.

SEC/A/4: Cutting from ‘Melody Maker’ advertising a Pink Floyd gig at UCL, circa 1969.

Series two in the collection consists of publications either written by, or related to, past students and staff. There are also a couple of books which relate to the history of the university, along with some university produced publications. A small sub-series of articles taken from Pi Magazine, which were previously framed, are also included.

The third series comprises photographs and artwork related to UCL, the Student Union, and UCL students and staff. Included are some of the earliest photographs of the Wilkins building, portraits of Student Union presidents and officers, photographs of sports teams, plus various student association performances and events.

SEC/C/1/21 Photograph of a Dramsoc play on the Portico, c.1947.

The remainder of the collection includes a large series of academic, sporting, commemorative and military medals, and a small series of objects. Included is a Botany Laboratory microscope, a silver cup awarded for first place in the UCH Athletic Club pole jump, a variety of UCL and SU branded memorabilia, such as a car bumper badge, silk tie, union badges and miniature ceramic models. One particularly interesting object in this final series is a Royal Doulton tyg cup which was awarded for first place in the UCH Athletic Club’s ¼ mile handicap race (pictured below). A tyg is a drinking vessel with three or more handles and is traditionally used for sharing a celebratory drink!

Tyg awarded for the UCH ¼ mile handicap race in 1890, and two medals, in the process of being accessioned.

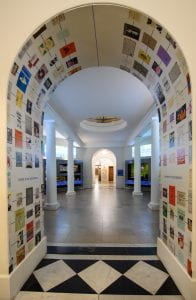

A considerable amount of the collection has formed part of the current Octagon Gallery exhibition, ‘Generation UCL’, which explores the lives of UCL students over two centuries and the foundational part they play to the story of the university. Mounted in the run up to UCL’s bicentenary celebrations in 2026, the exhibition also marks 130 years of Student’s Union UCL.

One of the entrances to the Gen UCL exhibition, on now at the Octagon Gallery.

If you would like to further explore the collection it can now be viewed online at https://archives.ucl.ac.uk/ and by typing ‘Student Ephemera Collection’ into the search bar.

To make an appointment to view the records, or for any queries regarding the collection or the catalogue, please contact us at spec.coll@ucl.ac.uk.

To read more about the Generation UCL exhibition visit the exhibition project page.

Cataloguing the papers of Anthony Lester, Lord Lester of Herne Hill

By utnvweb, on 12 December 2023

By Martin Woodward, Cataloguing Archivist, Lester Papers

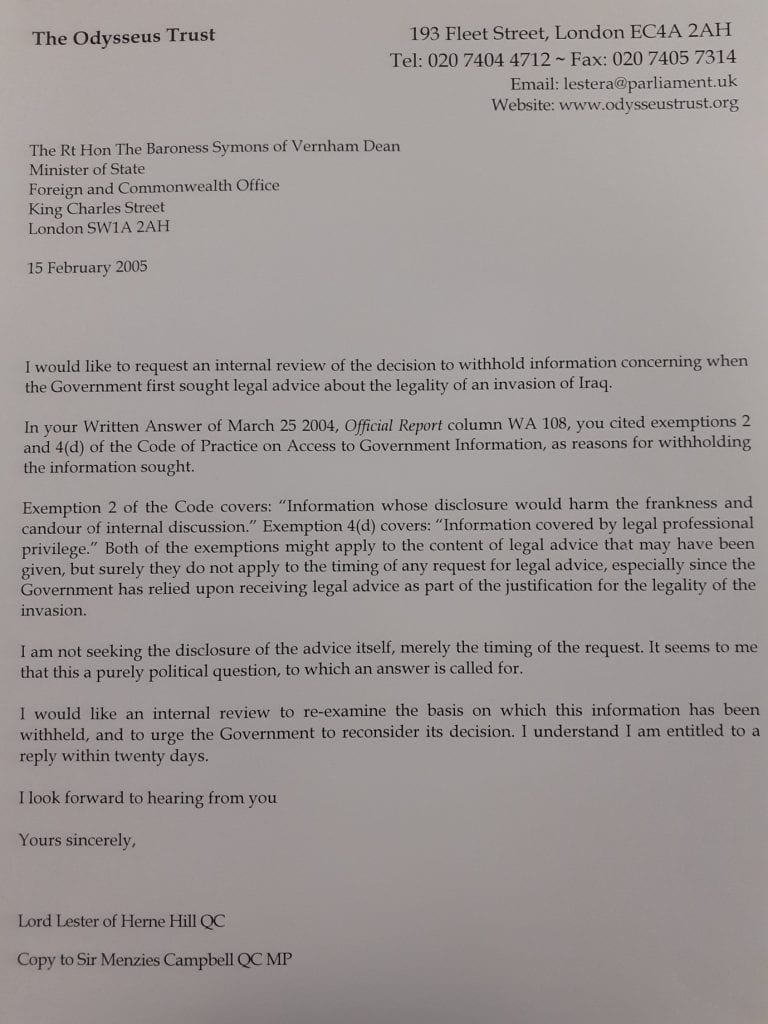

The Project to catalogue the Papers of Anthony Lester, Lord Lester of Herne Hill (1936-2020) is now complete. Lester was an eminent barrister (QC), Special Adviser to Labour Home Secretary Roy Jenkins in the 1970s, and for twenty-five years a Liberal Democrat peer. During his time in the Lords, Lester’s Private Member’s Bills and tireless political work on behalf of human rights, equality and free speech helped bring about the Human Rights Act 1998, the Civil Partnership Act 2004, the Equality Act 2010, and the Defamation Act 2013.

Lester held visiting professorships at UCL, and we are very pleased that the Lester Papers are now available for research at UCL Special Collections.

Boxes of files from the Lester archive as received from the donor

There were two main elements to the project: appraisal and cataloguing. A careful process of appraisal has seen the reduction of an original deposit of 59 banker’s boxes of files to thirty smaller archive boxes of papers. The priorities during appraisal were to retain anything written by Lester, such as publications and correspondence, and records of House of Lords Written Answers where Lester asked the question. Accompanying documents, such as official publications, reports, and policy statements, in which Lester had no involvement, were generally not retained.

This process led to three main classes of material for cataloguing.

The first of these was Lester’s Written Answers, principally in the form of an apparently comprehensive chronological run of six files of Lester’s questions to Government Ministers covering the years 1993-2005, and a scattering of similar records elsewhere. One cannot fail to be amazed at the sheer number of questions put by Lester in the House of Lords during this period.

LESTER/207: Lester was co-founder and Chairman (1991-1993) of the race relations and civil rights think tank the Runnymede Trust. Image published with the permission of the Runnymede Trust.

The second category of material was Lester’s publications: book chapters, articles, speeches, lectures, letters to the press, and so on. Here also there was a very carefully arranged chronological run of papers by Lester in nine files covering the years 1964-2011 (the index lists 335 items). The publications demonstrate all Lester’s main concerns in Parliament: race relations, human rights, equality, constitutional matters, Northern Ireland, European law, and free speech. Lester’s written output is immense, as is the depth of his legal knowledge. There are also several other files of Lester’s articles and speeches, which are recorded separately in the catalogue. Lester’s Jewish origins are often reflected in his writings, such as when he refers to his father’s witnessing the activities of Sir Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts in the East End of London in the 1930s.

The third category was the subject files (such as papers on international Human Rights), reduced by appraisal largely to Lester’s own correspondence. Here again there was an original alphabetical subject file classification between LESTER/1 (Blasphemy) and LESTER/149 (Venice Commission), which has been followed in the online catalogue; thereafter the papers are not arranged in any recognisable order. The records of Lord Lester’s Office are in general extremely well kept. The subject files illustrate Lester’s work on behalf of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in the early 1980s and the Liberal Democrats in the 1990s, and (principally) his political interests in the House of Lords between 1993 and 2015. The files contain letters, amongst many others, from Tony and Cherie Blair, Margaret Thatcher, Jack Straw, Shirley Williams, and Lord Scarman. Some of the correspondence is more personal in nature, such as a letter from Lester to Mohamed Al Fayed in 1994, thanking him for allowing Lester and his wife, Katya, to stay at Al Fayed’s Scottish estate.

The correspondence is notable for the evident warmth and respect in which Lester was held by his many contacts in the legal profession, politics and the media.

LESTER/195: letter from Lester to the Minister of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 2005, seeking a review of the Government’s decision to withhold information about the invasion of Iraq.

LESTER/165: one of Lester’s doodles, dating back to his days in the SDP.

Nor is humour lacking: a letter from the Parliamentary Group for World Government addressed to ‘Lord Anthony Leicester’ prompted the response: ‘Incidentally you might wish to note the spelling of my name because the Earl of Leicester would be upset’. Again, when Lester was asked his name and professional background by an interviewer in 2007 he replied: ‘Well, that’s not so easy because I changed my name when I became a member of the old people’s home but I was born Anthony Lester and I am now Lord Lester of Herne Hill QC’. And then there are the doodles. There is a scattering of these throughout the papers.

Government legislation on equality and human rights has produced enormous social change in this country since the Roy Jenkins era. It is my belief that the Lester archive will be a very important resource in future in understanding how that change occurred. The catalogue is available on our archives catalogue

An Unexpected Discovery

By Katy Makin, on 23 November 2023

The folklorist Katharine Mary Briggs (1898-1980) shared her love of folk tales and storytelling through her many publications, community work and children’s groups. A former president of the Folklore Society, a small archive of her papers and correspondence is now owned by the Society and deposited with UCL Special Collections as part of the Folklore Society Archive.

Katharine Briggs as a child, unknown artist. Image supplied by the Folklore Society

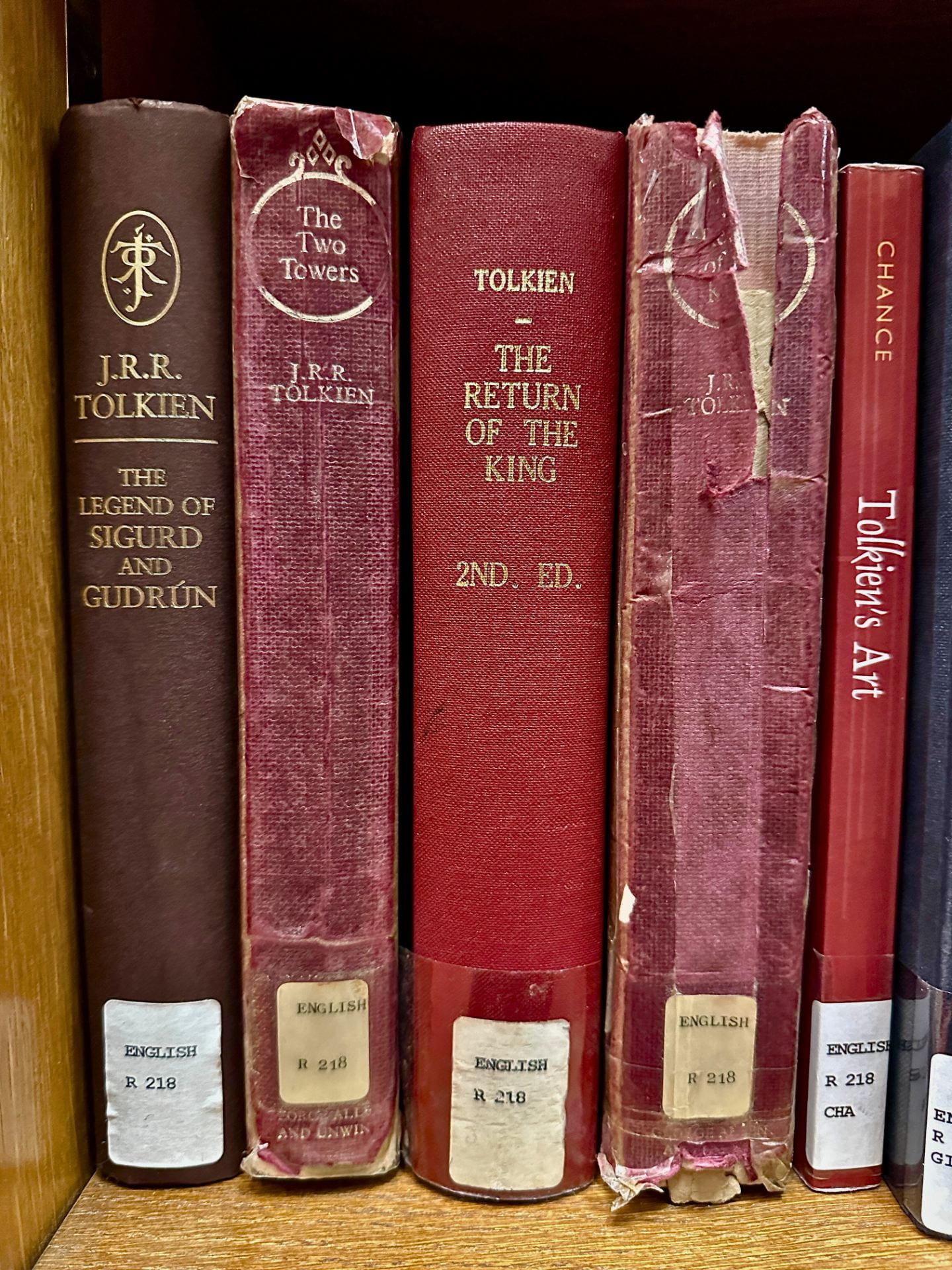

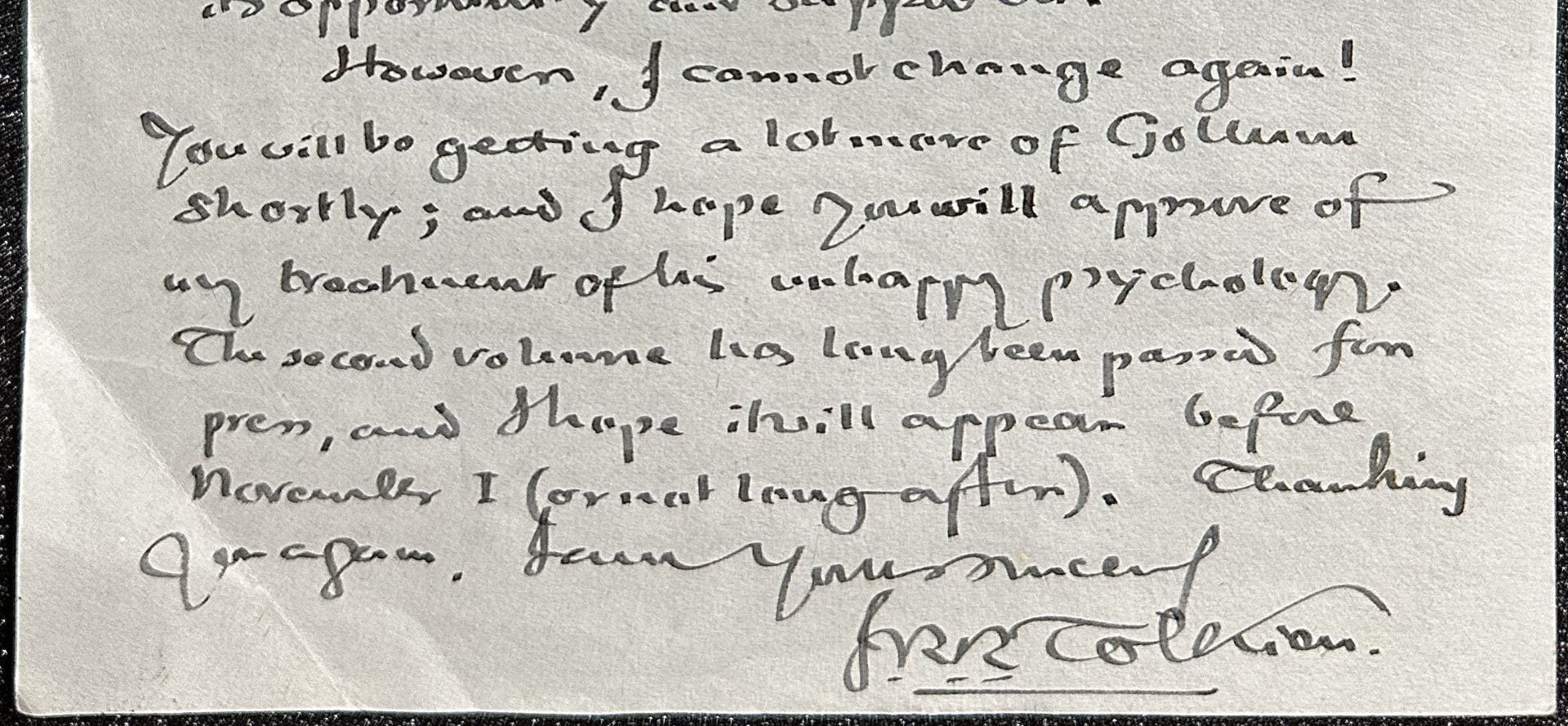

Although Briggs’ papers in the Folklore Society Archive are currently uncatalogued, access can still be provided for researchers who have the patience to work methodically through her letters, notes, poems and photographs. The letters in particular are tricky to use as they are only roughly sorted into bundles that span several years. But patience can be rewarded; whilst checking the bundles of letters ahead of a researcher’s visit as part of our data protection procedures I came across an unpublished letter from the author JRR Tolkien to Katharine Briggs.

Tolkein’s books in UCL Main Library.

Two letters from Briggs to Tolkien are now part of the Tolkien archive held at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. In her first letter of October 11th 1954, Briggs describes being held in suspense, “reading and re-reading” The Fellowship of the Ring, and asks whether the second part of The Lord of the Rings will be published before Christmas. For her, the only flaw is the alteration of the Gollum incident from the way it had been told in The Hobbit and the nature of Bilbo’s finding of the One Ring, which had been her favourite part. In The Fellowship of the Ring, she says there is an implication that Bilbo thought of the Ring as a gift, which seems to her unlikely. On a minor point, she also found the description of Bilbo running away from Gollum with his hands in his pockets unconvincing: “You would never run away from a furious adversary with your hands in your pockets – try it and see. Particularly in a dark and narrow place”. [Letter from Katharine Briggs to JRR Tolkien, 11th October 1954, Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Tolkien Family Archive (uncatalogued)]

Tolkien’s response came a few days later, on the 13th October. This is the letter now found in Briggs’ papers in the Folklore Society archives. He thanks Briggs for her appreciation of his work, and addresses some of her comments about the “Bilbo-Gollum business”. He confirms that Gollum would never willingly have gifted the Ring to Bilbo, but under the “evil pressure of the Ring and the cry of thief”, in one version of events Bilbo makes up the story of the Ring being a present.

Addressing her challenge, he says:

“Even in the abbreviated version of the ‘prologue’ Bilbo did not run away with his hands in his pockets. (I have not led an entirely sheltered life, and have no need to try it out). In the full version this is clearer.”

Tolkien ends his letter with good news: The Two Towers has gone to press and he hopes it will appear by November 1st (or not long after). In in the end, Briggs did not have much longer to wait as it was published on November 11th 1954.

Letter from JRR Tolkien to Katharine Briggs, 13th October 1954, Folklore Society Archive T273, UCL Special Collections. Copyright of the Tolkien Estate and reproduced here with permission.

Briggs was effusive in her thanks. “The news that The Two Towers is to come out in November is the best I have heard for some time. Then we shall be all clamouring for The Return of the King (I hope this is Aragorn); and when we get that we shall be undoubtedly happy for a good many years.” In the meantime, she had purchased a new edition of The Hobbit and agreed that the full account of the meeting with Gollum is much clearer here than in the summary given in The Fellowship of the Ring. [Letter from Katharine Briggs to JRR Tolkien, 21 Oct 1954, Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Tolkien Family Archive (uncatalogued)]

Briggs, Katharine M. (1953) The personnel of fairyland : a short account of the fairy people of Great Britain for those who tell stories to children / by K.M. Briggs / illustrated by Jane Moore. Oxford: Alden Press.

Copies of Katharine Briggs’ many books can be found around UCL Libraries, including one of her earliest collections of stories: “The Personnel of Fairyland: A short account of the fairy people of Great Britain for those who tell stories to children” (Stores FLS 12 BRI ) which has the charming frontispiece pictured above. Based on an image of medieval folklore, it includes a witch, an enchanted castle, a Friar raising his imps, a Fairy Ring, and a “Witch rideing on the Devill through the Aire”.

Some of her other books popular with children are part of the IOE Library’s collections, including “Nine Lives: Cats in Folklore” (IOE Library FOLKTALES 398.2 BRI) and “Abbey Lubbers, Banshees and Boggarts: A Who’s Who of Fairies” (IOE Library FOLKTALES 398.24 BRI).

If you’re visiting the IOE Library you can also borrow a copy of JRR Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings” at the same time (IOE Library FICTION TOL).

Briggs, Katharine M. (1980) Nine lives : cats in folklore / Katharine M. Briggs ; with illustrations by John Ward. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

The Folklore Society archive and rare books library are deposited at UCL Special Collections. For further information and to make an appointment, contact us.

Other archive material of Katharine Briggs and her family, including her sister Elspeth, is held at Leeds University Special Collections (MS 1309).

With thanks to Catherine McIlwaine, Tolkien Archivist, Bodleian Libraries University of Oxford, for her assistance. The letters from Katharine Briggs to JRR Tolkien are part of the uncatalogued family archives and not currently available for research.

‘There is no university without its students’

By Leah Johnston, on 16 October 2023

On the 25th September a new exhibition, ‘Generation UCL: 200 Years of Student Life in London’, opened in UCL’s Octagon Gallery. The exhibition explores two centuries of student life at UCL, placing them at the centre of the university’s history. Mounted in anticipation of UCL’s bicentenary celebrations in 2026, it also marks 130 years of Students’ Union UCL, one of the largest student-led organisations in the world. Material has been contributed by UCL Special Collections, UCL Museums, Students’ Union UCL, and UCL alumni.

A photograph of one of the lightboxes in the exhibition stating that there is no university ‘without its students’.

The exhibition is part of the wider Generation UCL research project, which looks to explore the lives of UCL students and present them as the real ‘founders’ of the university.

Over the past 9 months, members of the Special Collections team have been working alongside Professor Georgina Brewis and Dr Sam Blaxland, of the Generation UCL team, to select and prepare material for display. Fifty of the items featured in the exhibition are taken from the University College and IOE archive collections, making it one of the largest Special Collections exhibitions in recent years.

Members of the North Star team installing Institute of Education items

Items included range from official UCL publications and records, such as student record cards, files and calendars, to union and society magazines and posters. Thanks to a recent donation by Students’ Union UCL of the collection of UCL alum, Professor Mark Curtin, we have had the opportunity to display a number of objects too. These include a 1940s blazer and silk scarf worn by Geography student Enid Sampson, a UCL Botany department microscope, academic medals and union badges.

Other objects were uncovered in the process of putting together the initial longlist. A visit to the College Archives silver store back in April resulted in the discovery of a full set of 1950s cutlery (including fish knife!) that had been used by students at Bentham Hall.

Bentham Hall cutlery on display alongside a 1918 Union Magazine cartoon, showing diners crowding around Refectory menus.

With a vast amount of material to choose from the process of shortlisting was tough! However, some clever design on the part of Polytechnic studio meant that we have also been able to display material that would otherwise have been left out. The two arches that lead into the gallery have now been covered in digitised copies of publications, posters, adverts, and invitations, which were created for, or by, UCL students. If you are in the space, see if you can spot a Student’s Guide to Computers from 1996, an advert for a 1960s Pink Floyd gig and a 1981 Student Survival guide with the title ‘Don’t panic: it’s too late anyway!’.

A snapshot of one of the arches leading into the Octagon Gallery

The exhibition is open now until August 2024 and is free for all to attend. For more information about the creation of the exhibition visit the exhibition project page.

Gaster Cataloguing Project: Part 2

By Katy Makin, on 22 September 2023

In our previous blog post we introduced our project to catalogue the archive of Moses Gaster, and looked at some of the letters sent to Gaster on topics as diverse as Sunday trading and Hebrew braille. In the second of our two posts relating to the project, Gaster Project Cataloguer Israel Sandman discusses Gaster’s charitable activities.

From the Gaster Archives: A Glimpse into Moses Gaster’s Charity Activities

By Dr Israel M. Sandman, Gaster Project Cataloguer

Moses Gaster was a multifaceted person. He was the chief rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in London, and, by extension, of all Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ congregations under the British Empire. He was a polymath academic scholar, with strong focuses on comparative folklore and linguistics. He was a key figure in the emergence of modern Zionism. And he was a go-to person for Jews worldwide, for help with their various needs and wants.

Charity Appeals to Gaster:

Daily, Moses Gaster received multiple charity appeals, some in the post, and some in person during his reception hours. While he donated from his personal funds to Jewish and other worthy causes, as seen in receipts, lists of donors, and gentle reminders to honour his pledges, what he could do from his own funds was a mere drop in the ocean of need.

![[Image and Transcription of Receipt for Donation made by Gaster (file 131, item 44)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2918-1024x652.jpg)

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 131/44]

22, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

346

March 15, 1900

Received from Dr. Gaster the sum of One Guinea as a donation to the Medical Fund.

£1-1-0

[Signed] Secretary

Charitable Funds on a Community Level:

Addressing the vast needs faced by people in fincial hardship required charitable funds on a community level. Charitable funds established in the Jewish community enabled Gaster to help the Jewish individuals and worthy institutions that turned to him from Palestine, North Africa, elsewhere in the Near East, India, West Indies, Eastern and Central Europe, the East End of London, the length and breadth of Britain, and elsewhere. We shall examine two such funds, one of which was well established, and another of which was an ad-hoc fund set up to meet a specific need.

Case 1: Gaster Helps S. Edelstein via the Board of Guardians of the Poor of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue:

Shalom Edelstein was a Romanian Jew residing in London’s East End, which at the turn from the 19th to the 20th century was the first place of settlement for many Jews from Central and Eastern Europe. Reading between the lines of Edelstein’s 21 March 1899 postcard to Gaster, written in ornate Hebrew full of allusions to classical Jewish literature, and in which he mentions his ill health, one gets the impression that Edelstein was more a man of the mind than a man of the body, and that he shared interests with his “landsman” Gaster.

| London 21/4/99 כבוד הרב החכם הבלשן סופר מהיר בלשונות החיות, רב ודרשן לעדת הפורטוגעזים, בעיר הבירה לונדן, והמדינה וע”א כש”ת מו[“]ה ד.ר. גאשטער נ”י. הנני בזה לכתוב למ”כ את רשומתי, כמו שבקש מאותי, אולי יאבה לכבדני במכתבו, ומפני כי מעת ראיתי פני כ”מ, לא נתחדש שום דבר, – רק שאני חלש מאד, ואנני בקו הבריאה, עד כי בכבדות אוכל לקום ממשכבי, – לכן אקצר ואומר שלום. והנני מוקירו ומכבדו כערכו הרם. פ”ש, כשמי, – שלום הן תוי ונוי S. Edelstein 17 Winterton St. Commercial Road, E. |

![Image of S. Edelstein’s 21 March 1899 Mostly Hebrew Postcard to Gaster (file 117, item 9)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2919-238x300.jpg) |

| London 21/4/99

His honour, rabbi, sage, linguist, speedy scribe in living languages, rabbi and preacher to the congregation of Portuguese [Jews] in the capital city London and the [entire] country, and furthermore [possessor of] the ‘crown of Torah’, our Master Rabbi Dr Gaster, may his lamp shine! I am hereby writing my address [Hebrew: רשומתי or רשימתי] to his honour, as requested by him. Perchance he will desire to honour me with a letter? On account of the fact that since I have seen his honour’s face, nothing new has occurred – aside from my being very weak: I am not keeping in good health, so much so that it is only with difficulty that I can arise from my couch – I will therefore be brief, and say ‘farewell’ [Hebrew: Shalom]. I hereby hold him precious and honour him, in keeping with his lofty worthiness, Greetings of Shalom, in keeping with my name, Shalom [Peace], being my mark and my charm |

|

[Image, Transcription, and Translation of S. Edelstein’s 21 March 1899 Mostly Hebrew Postcard to Gaster. UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1. Formerly file 117, item 9]

Multiple Communications Between Edelstein and Gaster:

This was not their first communication. In the postcard, Edelstein refers to their having had a face-to-face meeting; and he notes that Gaster had asked him for his reshuma / רשומה [or: reshima / רשימה], presumably meaning his address. Presumably, this indicates that Edelstein had asked Gaster for assistance; and that Gaster was going to try and help him. Three days later, on 24 April 1899, Edelstein sent another postcard to Gaster, this one in Romanian. Apparently, to help Edelstein, Gaster turned to the charity board of the synagogue of which he was rabbi, the Board of Guardians of the Poor of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue.

![[S. Edelstein’s 24 March 1899 Romanian Postcard to Gaster (file 117, item 20)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2920-1024x799.jpg)

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archives, GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 117/20]

The Board of Guardians’ Approval:

Nine days later, on the 3rd of May, Gaster received a memo from the Board of Guardians. They would cover Edelstein’s train fare from London to Liverpool, and his boat fare from Liverpool to New York. However, that cost £5, and they did not have anything additional to offer Edelstein. Although that would mean that Edelstein would arrive penniless in New York, the Board had reason to believe that Edelstein would nonetheless be admitted to the USA. It seems that Edelstein was permitted to enter the United States, for we have a long letter, in Romanian, which he sent to Gaster from New York. Towards the end of that letter, he updates Gaster about a certain D. Gottheil. The Gaster Archive contains letters to Gaster from a Professor Richard Gottheil, relevant to the writing of Jewish Encyclopedia articles and possibly to Zionism; but it is unclear whether there is a link from Richard to D. Gottheil.

London May 3rd 1899

Dear Dr. Gaster,

re – S. Edelstein

With difficulty I succeeded in securing a passage for this man per “Tonfariro” which will sail from Liverpool on Saturday next. The fare came to £5 which includes railway fare to Liverpool so that I have nothing to hand over to the man. I am informed that by this line it is not necessary for him to have a certain sum of money in his pocket on arrival in New York.

Yours faithfully,

J.Piza

The Board

would do nothing

for Haham Abohab

J.P.

[UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1. Formerly file 118/11]

The Limitations of Working Through the Board of Guardians of the Poor:

In addition to the limits of what the Board felt capable of doing for Edelstein, at the end of their memo, the chairman adds an apologetic side note. He mentions that the Board did not approve a different request, for funding for a certain Hakham (rabbi/sage) Abohab. It is noteworthy that Edelstein was a Central / Eastern European Jew, while the name Abohab indicates a Jew from the Islamic countries. Although the Spanish and Portuguese tradition is more aligned with the traditions of the Islamicate Jews, the Spanish and Portuguese Board approved Edelstein’s request, not Abohab’s. This seems to indicate an objectivity on the part of the Board. It appears that the reason for the Board’s limits in giving was the fact that the Synagogue was experiencing financial difficulties; and in order for Gaster to carry out his wide range and full scale of charitable activities, he needed additional sources of funding, beyond those available through his own congregation

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 131/85]

Dear Sir,

The Gentlemen of the Mahamad [executive committee] invite your attention to the Statements of Accounts of the Synagogue, and the Report of same for the year 1899, which have been circulated amongst the Yehidim [members] of the Congregation, & I have particularly to point out that the result of the year’s working shews a deficit of £595.-, and that the Elders have been compelled to sell out Capital Stock to meet this & other deficiencies accrued since 1895, amounting in the aggregate to £1608.-

This position, which is a very serious one, was duly considered by the Elders at their recent Annual Meeting, and they requested the Mahamad to take such steps as they might think necessary, to call attention, in the first instance …

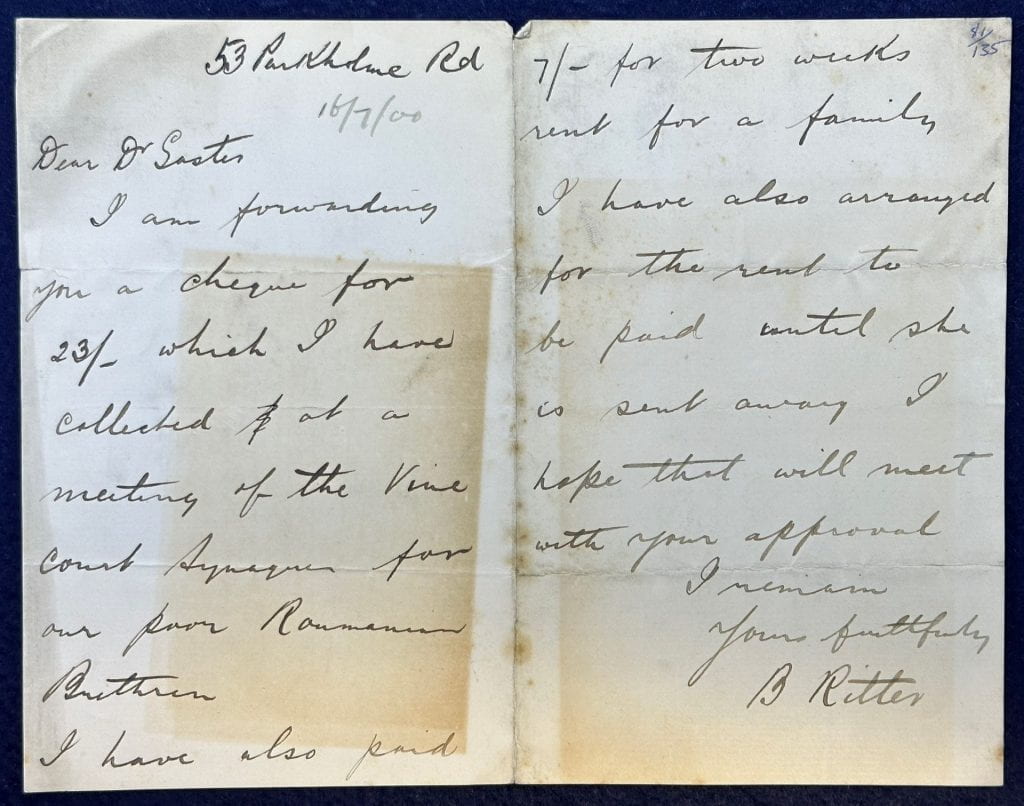

The Ad Hoc Fund for “Our Poor Roumanian Brethren”:

The Crisis of Romanian Jewry:

One additional source of charity funds, independent of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue and its Board of Guardians, is an ad hoc fund that Gaster seems to have created himself. The fund is for ‘our poor Roumanian Brethren’, as described in Benjamin Ritter’s letter to Gaster, accompanying a cheque from a collection taken up in Vine Court Synagogue. At this juncture (around 1900), Romanian Jews were experiencing an unusual level of persecution, and were seeking to leave Romania. From all directions, individuals and institutions were turning to Gaster for solutions and financial help; and Gaster did respond.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive. GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 135/20]

The Vine Court Synagogue:

The Vine Court Synagogue was a congregation of Eastern European Jews, in the Whitechapel section of London’s East End. As noted, the East End was the first place of settlement for many Eastern European Jews. Thus, this congregation would have had particular sympathy for the Romanian Jews, as did Gaster, who was a Romanian Jew, and who received many charity appeals from the community of his origin. Gaster’s relationship with the Eastern European immigrant Jews of the East End came to good use in his finding the best ways to help his Romanian brethren.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1 [formerly file 135/81]

Dear Dr Gaster

I am forwarding you a cheque for 23/- which I have collected at a meeting of the Vine Court Synagogue for our poor Roumanian Brethren. I have also paid 7/- for two weeks rent for a family. I have also arranged for the rent to be paid until she is sent away. I hope that will meet with your approval.

I remain

Yours faithfully

B Ritter

The Blaustein (Bluestein) Family and their Relocation from Romania to London:

Another Romanian Jewish party helped through Gaster’s efforts is the Blaustein (Bluestein) family. (The surname seems to have been anglicised from Blaustein to Bluestein.) While it would take further research to try to discover the source of the funds Gaster used to help them, and to piece together this family’s full story and the relationship between all the family members, the partial story that emerges from the documents below is worthwhile in and of itself.

Mrs. Ch. Bluestein was a Romanian Jewish widow. One of her sons had a disability. Gaster had helped the family, and now they were established in London. The son with the disability was gainfully employed. Another son, who was to be married, ‘also earns a nice living’. Mrs Bluestein writes to invite the Gasters to the wedding, and to express her gratitude to Moses Gaster.

![Image of Personal Letter of Gratitude to Gaster, Accompanied by a Wedding Invitation (file 131, item 58)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2932-893x1024.jpg)

UCL Special Collections. Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1 [fomerly file 131/58]

Lower Chapman Str.

Commercail [sic] Rd E

London March 20 1900

Reverand [sic] Sir

I beg to enclose your invite for my son’s wedding. I hope you will come, as you was always a good friend to me when in need so I am happy to let you know of my joy thank God my son is doing a respectable match – and I hope you will live to see joy by your dear children in happiness with your dear wife I am the widow whom you helped to bring over the crippled son from Bucherst, he is grateful to you as he thank God earns £2 – 0 – – weekly – and is quite happy – and my son that is to be married also earns a nice living. We often bless you for everything & I am pleased to tell you of my joy as well as I did my trouble. With best respect, yours gratefully,

Mrs Bluestein

Printed Wedding Invitation Addressed to the Gasters, Sent by Mrs Ch. Bluestein. The Hebrew line at the top is from the prophecy of restoration in Jerimiah 33:11, and is used in the Jewish wedding liturgy: ‘A voice of joy and a voice of gladness, a groom’s voice and a bride’s voice’.

In Summary

Gaster was heavily involved in charity work, on a scale that required communal funding. Although the Board of Guardians of the Poor of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, Gaster’s congregation, provided funding for those beyond their own community, they were too financially limited to finance the full scope of Gaster’s work. Thus, we see that Gaster raised charity funds elsewhere, too. One example of this is Gaster’s ad hoc fundraising network on behalf of Romanian Jewry, which at the turn from the nineteenth to the twentieth century was undergoing strong persecution. We see how Gaster met this challenge, and we see the sweet fruit of his labour.

Blog post by Israel M. Sandman

Gaster Cataloguing Project: Part 1

By Katy Makin, on 20 September 2023

Deborah Fisher, Gaster Project Cataloguer, shares some of her work.

We have recently started an exciting new project to fully catalogue the archive of Rabbi Dr Moses Gaster (1856-1939) and make the collection more easily available for research. Supported by external funding, the project runs from August 2023 to March 2024, and two project cataloguers will be carrying out the work to sort, list and catalogue Gaster’s extensive correspondence.

The Gaster Papers is the largest and most significant Jewish archive collection at UCL Special Collections. The bulk of it is correspondence between Dr Gaster and a range of individuals and organisations across the Jewish and wider community. It includes both incoming letters and copies of outgoing ones, and comprises around 50 linear metres of material.

Gaster was a Jewish communal leader, prominent Zionist and prolific scholar of Romanian literature, folklore, and Samaritan history and literature, as well as Jewish subjects. Born in Bucharest, he was expelled from Romania in 1885 because of his political activities. He settled in Britain and was appointed Haham (spiritual head) of the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community, and later also Principal of the Judith Lady Montefiore College in Ramsgate. He was a founder and president of the English Zionist Federation and played an important role in the talks resulting in the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

The archive also has wider significance beyond Moses Gaster himself and is an important resource for research into late 19th and early 20th century history, both within and beyond the Anglo-Jewish community. Gaster corresponded with a huge range of individuals and organisations: a biographical index of Gaster’s well-known correspondents for the period 1870-1897 includes nearly 400 names, including rabbis; Jewish, Christian and secular scholars; politicians; financiers; doctors and even royalty. He received correspondence from Britain, Europe, America, the Middle East, India, South Africa and Australia.

Letters from the archive

The letters received by Gaster cover a broad range of topics, such as aspects of Jewish law and religious practice, charity appeals on behalf of individuals and organisations, and meetings attended or publications produced by Gaster for various societies including the Royal Asiatic Society, Society of Biblical Archaeology, and Folklore Society.

The samples below reflect the diverse nature of the correspondence, providing a glimpse into Gaster’s daily life and the tasks and responsibilities he undertook.

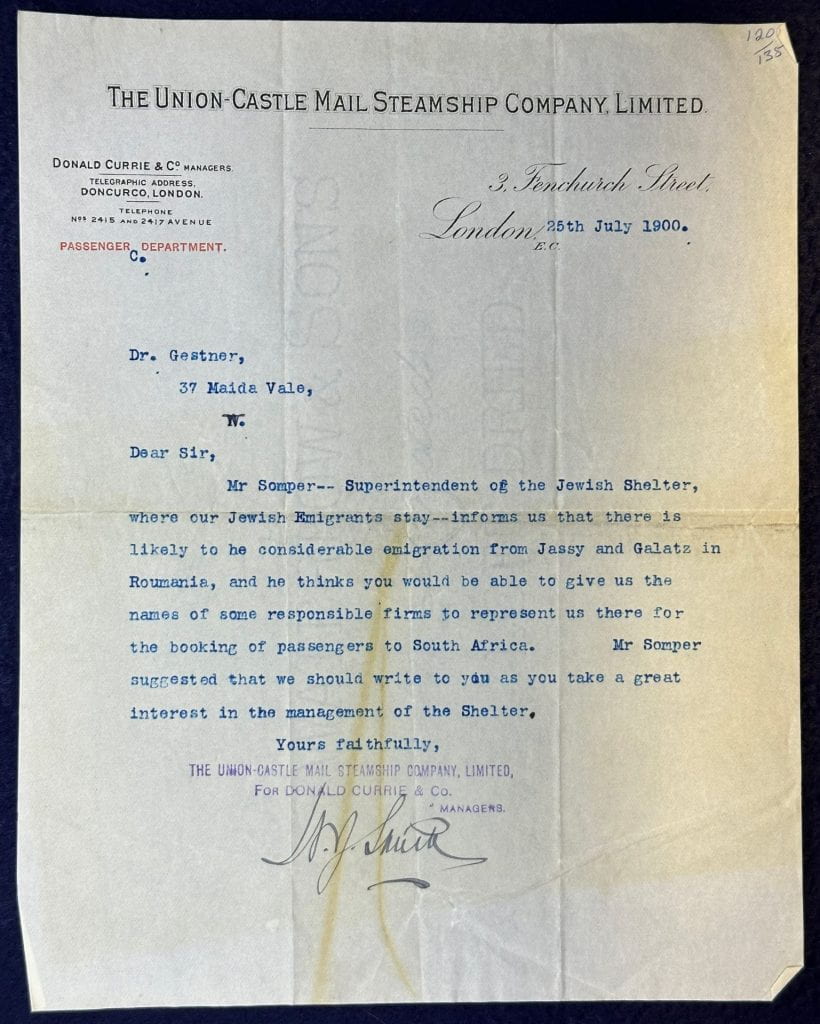

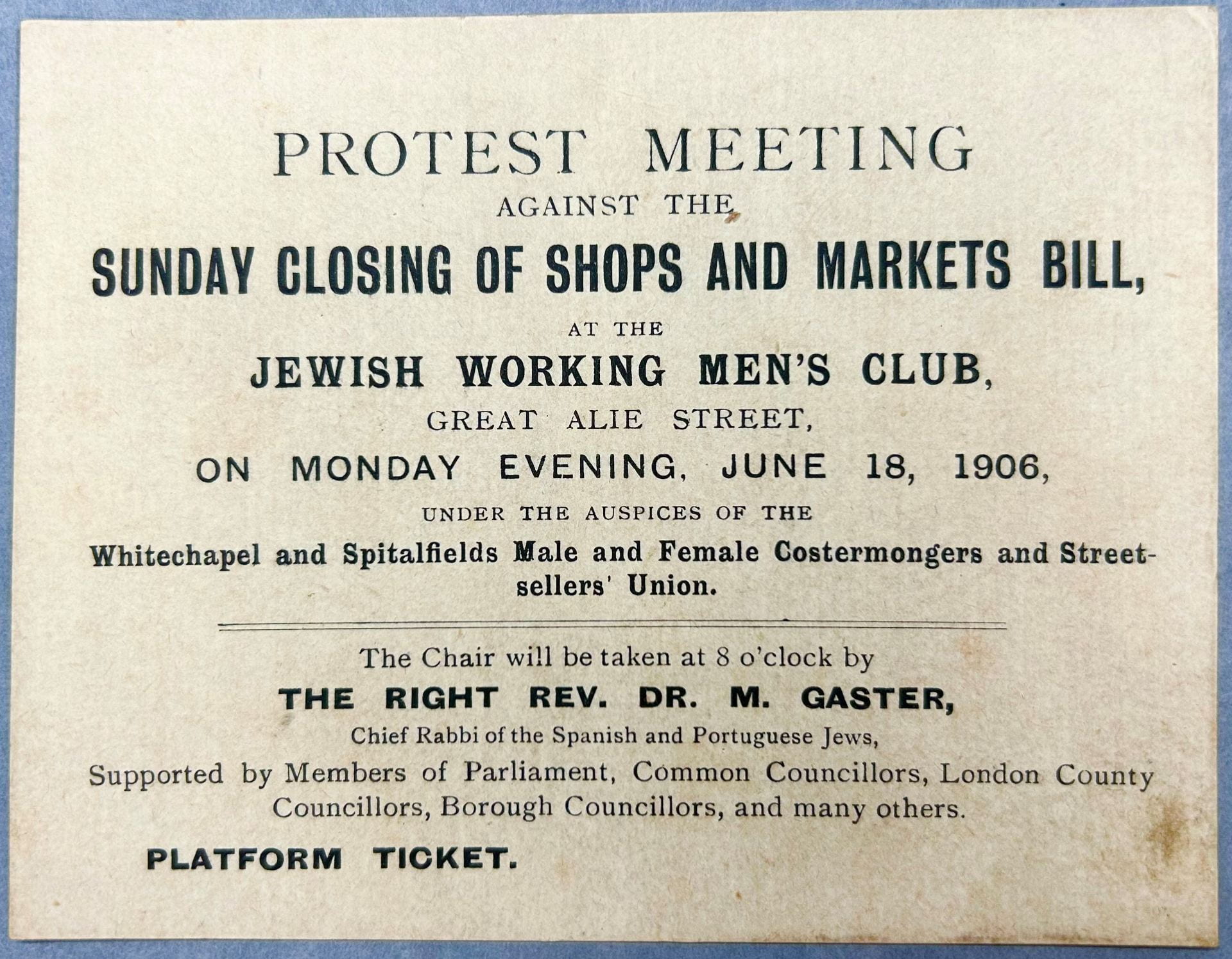

Shopkeepers and Businesses

In a letter dated 28 August 1896, Gaster is invited to attend a meeting in support of the Jewish Master Bakers. The Sunday Observance Laws and the Bread Acts of 1822 and 1836 prohibited bakers from baking on Sundays due to the Christian Sabbath, but as Jewish bakers were also unable to bake and sell bread on Saturdays (the Jewish Sabbath), they would only have stale bread to sell during the limited trading hours on Sunday as well as on Monday morning. Many Jewish bakers did bake and sell fresh bread on Sundays in violation of these laws; this met with opposition from Christian bakers, who felt that it gave the Jewish bakers a competitive advantage. This tension led to Christian bakers reporting these Jewish bakers to the authorities, so that they would be prosecuted and fined. The letter below, written on behalf of the Jewish Master Bakers, invites Gaster to a meeting to discuss the matter.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1

The restrictions on Sunday trading also affected other Jewish shopkeepers. The Gaster ephemera collection contains a flyer for a protest meeting against the “Sunday Closing of Shops and Markets Bill” in June 1906, at which Gaster was Chair.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/1/A/2/701

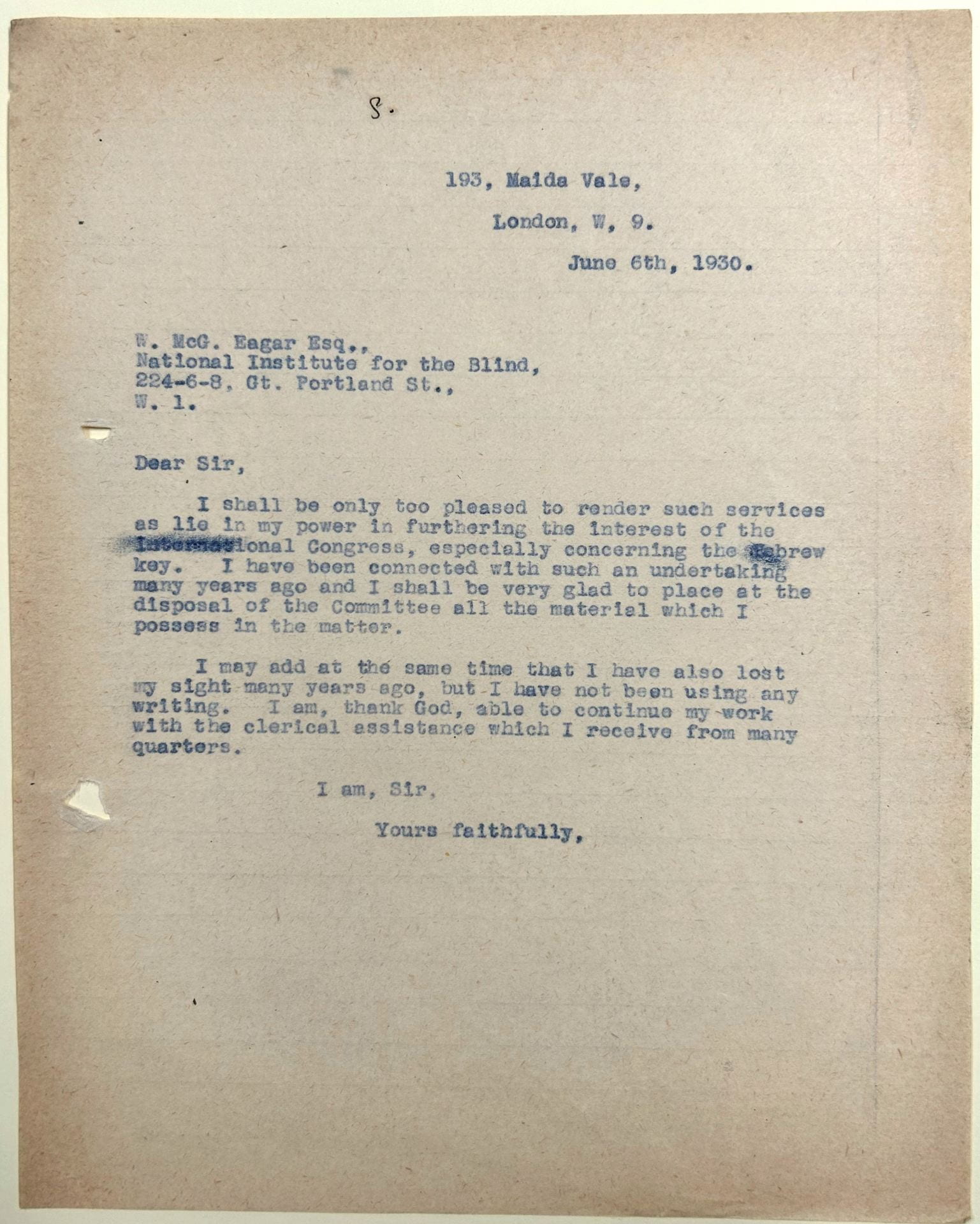

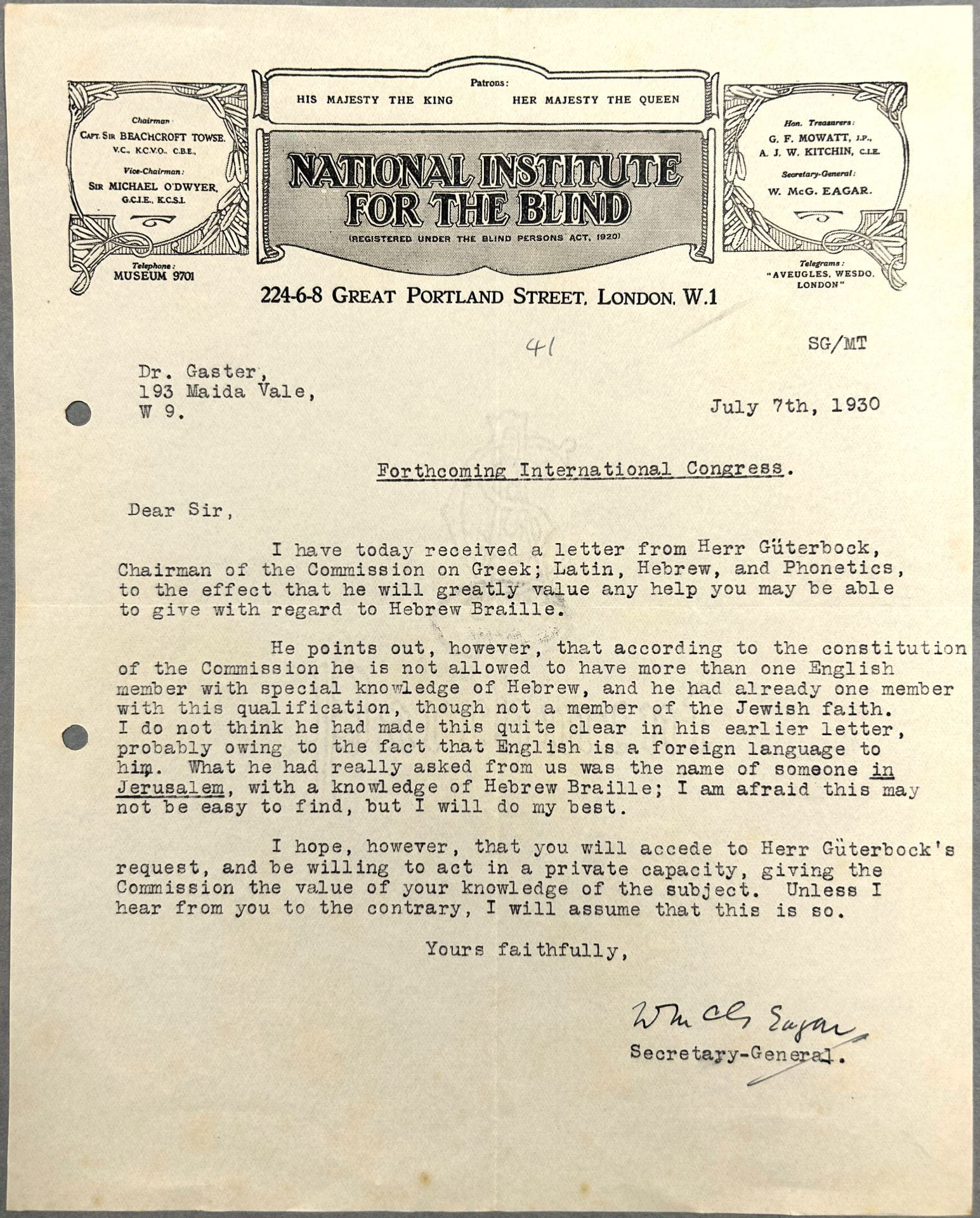

Hebrew Braille

Gaster was a highly respected scholar and linguist, and as such was asked by the National Institute for the Blind in June 1930 to serve on a commission for the development of a standardised Hebrew Braille code, to replace the regional variations already in existence. Furthermore, Gaster himself had lost his sight by this time, and so it may have been considered a matter of personal interest to him.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1

Gaster responded that he would be willing to participate in this work, and that he had previously been involved in the preparation of an alternative writing system for Hebrew for blind users, albeit different from Braille.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1.

Ultimately, Gaster does not appear to have been directly involved in the work of the Commission; it emerged that there could only be one English member of the Commission with knowledge of Hebrew, and that position had already been filled. But the National Institute for the Blind did continue to seek Gaster’s advice on the subject in a private capacity, as the letter below shows.

UCL Special Collections, Gaster Archive, GASTER/9/1

A broader discussion of the history of Hebrew Braille is found in the American Jewish Archives: https://sites.americanjewisharchives.org/journal/index.php?y=1969&v=21&n=2

Blog post by Deborah Fisher, Gaster Project Cataloguer, UCL Special Collections.

Our next blog post later this week will continue to explore the Gaster archive, with an article by Gaster Project Cataloguer, Israel Sandman.

Galton Laboratory Records

By Sarah Pipkin, on 7 September 2023

Leah Johnston, Cataloguing Archivist (Records), shares details of the Galton Laboratory archive.

Content warning: This blog includes details of records and objects that relate to racist, ableist and classist beliefs. The ideas within this material do not reflect the current views of UCL.

The Galton Laboratory Records form a collection of archives recording parts of the laboratory’s history, from its creation in 1904, up to the late 1990s. Much of the material was donated to UCL Special Collections in 2011, with some smaller accessions added since then. Over the past year the collection has been fully catalogued and is now all available to view online.

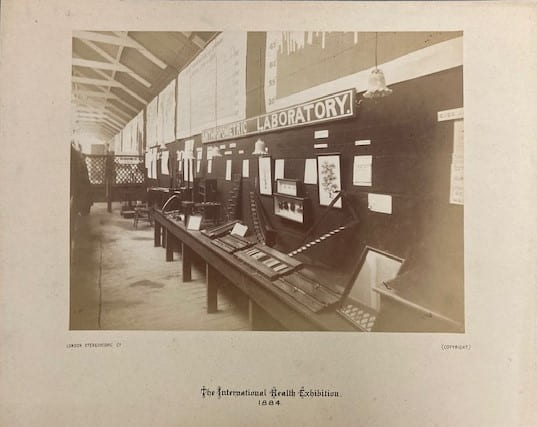

The origins of the Galton Laboratory at UCL can be traced back to 1904 when Francis Galton established the Eugenics Record Office in Gower Street, Bloomsbury. Although the laboratory was not officially part of the university at that time, a connection was formed with Galton endowing UCL with an annual £500 Fellowship of National Eugenics. In 1906 Professor Karl Pearson took over Directorship of the Eugenics Record Office, while still informally working alongside Galton. After Galton’s death in 1911, the residue of his estate was bequeathed to the university, under the condition that it was used to establish a Chair of Eugenics, whose role would be to direct research into ‘those causes under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations either physically or morally’.

GALTON LABORATORY/4/1/8 – Photograph of the Anthropometric Laboratory, South Kensington, 1884.

This early history of the laboratory is recorded in a series of administrative papers within the collection. Included is early correspondence between Galton, Pearson and P J Hartog (the then Academic Registrar), regarding their proposed scheme for a laboratory at the university, plus copies of Galton’s will and related planning for the establishment of a Chair of Eugenics. While these files include high level planning, other papers record more practical decisions, such as plans for the proposed new building. Below is an estimate for blinds to be supplied by James Shoolbred & Co. Ltd, including a small sample of green cloth.

GALTON LABORATORY/1/6/3 – Estimate for blinds from James Shoolbred and Co., including a sample of fabric, 1921.

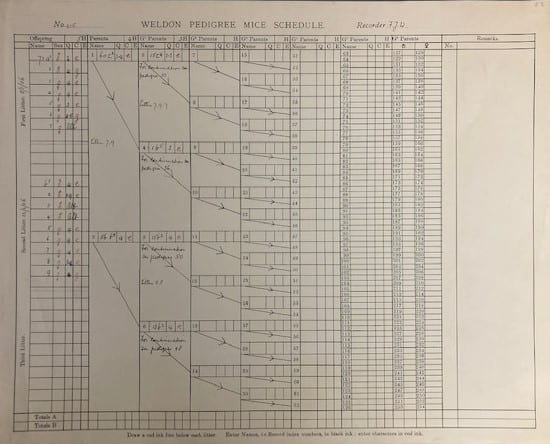

Other series include papers accumulated by the laboratory, records of laboratory publications (such as the Annals of Eugenics, The Treasury of Human Inheritance and Eugenics Laboratory Memoirs), and research working papers.

GALTON LABORATORY/2/3/3 – Weldon pedigree mice schedule, 1905-1906.

The remaining series consist of photographs, artwork, audio-visual material, and objects.

Artwork in the collection includes portraits of individuals connected either to Galton, or to the laboratory, alongside early watercolours of scientific specimens and samples. It appears from related annotations that they were either displayed in the laboratory or were used in their publications.

GALTON LABORATORY/4/2/6 – Watercolour illustrations of human eyes, 1915.

A series of photographs are similarly varied and were also used in publications, displayed in the laboratory, or kept as reference material. Included below is an image of Francis Galton seated on his porch, with his servant standing behind him and holding his pet Pekingese puppy.

GALTON LABORATORY/4/1/19 – Photograph of Francis Galton seated on his porch, with his servant Alfred Gifi, who is holding Galton’s Pekingese puppy, Wee Ling, c.1910.

This is contrasted against a more recent addition to the collection, which is one of three photographs showing women working in the laboratory in the early 1900s.

GALTON LABORATORY/4/1/17 – Women working in laboratory, early 20th century.

Alongside other UCL Library and Culture collections, the Galton Laboratory Records help to form a fuller record of the history of the laboratory and in turn, its legacy at UCL. If you would like to further explore the collection it can now be viewed on our online archives catalogue and by typing ‘Galton Laboratory Records’ into the search bar.

To make an appointment to view the records, or for any queries regarding the collection or the catalogue, please contact us at spec.coll@ucl.ac.uk.

Public History group projects 2023: Small Press, Big World – exploring the world of Wikipedia

By Joanna C Baines, on 14 August 2023

Jo:

Special Collections has been supporting the new MA in Public History since September 2022. As part of our support, we lead two group projects in Term 2 for Critical Public History, which is the core module all students take. These projects aim to equip students with real-world scenarios and experience, where they deliver an outcome to a client (in this case, Special Collections). Anna Fineman leads the other Special Collections project, which this year focused on creating an informal archive for the new UCL East campus.

My project involved putting information about our Small Press collections – which can be challenging to digitise due to the fact that they’re often still in copyright – online via Wikipedia. Small Press publications contain a wealth of work by artists, writers and publishers often collaborating to make independent works. This year our students James and Yuxuan worked on the 1960s art magazine 0 to 9, creating a brand new page for the title which includes a complete list of contributors to each issue. The page at present is in review stage, having initially been declined in April, so links will be updated on this post when it hopefully gets approved! You can still read the page whilst it is waiting for approval.

Huge thanks to James and Yuxuan who were an absolute dream team to work with this year!

James and Yuxuan:

For this short blog post, we will showcase the benefits of Wikipedia for information creation with student collaboration. We will also highlight some key strengths and pitfalls that come alongside Wikipedia development through the lens of working with the Small Press collection: 0 To 9 Magazine. Almost everyone has used Wikipedia for access to information, but to help ensure its continuation, it needs the support of contributors to help develop new articles.

Wikipedia is an encyclopedia with free content anyone can use, edit, and distribute. It is developed to have a neutral point of view. There are no firm rules, but contributors to Wikipedia must treat each other with respect and civility. For new users, Wikipedia also provides tutorials to help teach the basics. On creating a new page, various templates can aid your creation/development of an article!

Useful features to utilise when creating your Wikipedia page would be your sandbox, which allows you to play around with Wikipedia’s features in a less formal environment. Standardised elements include headings, citations, references and an infobox template.

Note: Although anyone can edit on Wikipedia, on published pages, people will check and edit what you post: Make sure to base your work on reliable sources. You can see a baseline of what reliable sources are from this Wikipedia page.

For our Wikipedia page, we included a brief description of what 0 To 9 Magazine was, some background behind the creators of the magazine, the production of the magazine, and the themes expressed by the contributors to the magazine. We then proceeded to list all the issues of 0 To 9 and more specifics about each issue.

At the bottom of the page, you can find further information about the impacts of 0 To 9 through the Supplements, Impact and Legacy subheadings and the various references.

As we worked on our Wikipedia page, we tried to focus on the magazine’s materiality of language and the distinction between visual art that it defies. We have also created a short video for this blog post, giving more details about the magazine, which you can watch below.

Winners of the 2023 Anthony Davis Student Book Collecting Prize

By Erika Delbecque, on 4 July 2023

We are delighted to announce the winners of this year’s Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize, which is open to students from any London universities. The prize is intended to encourage students who collect books, printed and manuscript materials. We received over thirty submissions from a total of nine institutions, with collections ranging from manuals on insect collecting, Penguin editions and books on the Tudors to 1890’s London and theatre programmes.

Results

Because of the high standard of the finalists’ presentations and collections, the panel decided to split the award between the two top-scoring candidates. Emma Treleaven, a PhD candidate at the London College of Fashion, is this year’s winner. Her collection, entitled My Own Two Hands: Books and Ephemera About Making Dress and Textiles Before 1975, focuses on learning materials on making clothes and textiles in domestic settings. Her collection is a way of preserving skills that are at risk of being lost, and she uses her collection to teach herself to make clothing in ways that aren’t taught anywhere outside of these historical printed materials. As the winner of this year’s competition, Emma will represent London at the ABA National Book Collecting Prize 2023.

Items from Emma’s collection on making dress and textiles before 1975

Items from Ben’s collection on the artistic and literary networks of Fitzrovia between 1920-1948

The runner-up candidate is Ben Baker, whose collection Artistic and Literary Networks of Fitzrovia: 1920-1948 impressed the panel with its ambition and clear focus. His collection explores the eclectic concentration of the so-called bohemian authors and artists who lived and worked in the region surrounding Fitzroy Square in London in the interwar period. Benjamin is studying for a BA Classics at UCL.

Items from Ben’s collection on the artistic and literary networks of Fitzrovia between 1920-1948

Tessa Roynon, a MA Library and Information Studies student at UCL, received a special mention for her collection The Formations of Toni Morrison, 1955-1980, which focuses on the pre-celebrity work of the African American Nobel Laureate.

The other finalists were:

- Grant, Jenny – ‘Read this – and tell others’: Inscriptions and the gifting of Polish books to British friends by the Polish Armed Forces, 1939-45

- Gray, Victoria – Prized Possessions: a collection of 19th- and 20th-century school prize books

- Mitra, Sudipto – Barefoot Ballers: Books on Football in India

- Shanker, Louis – My library, after David

Meet the finalists and see their collections

All seven candidates will be presenting their collections to the public in our UCL Rare-Books Club series over the next few weeks.

On Wednesday 5 July, Victoria, Jenny and Ben will present their collections in person at the UCL Bloomsbury campus. Book your place on Eventbrite and drop in any time between 12.30pm and 2pm.

On Wednesday 16th August, Sudipto, Emma, Tessa and Louis will present their collections. This is likely to be a hybrid event, which you can either join in person at the UCL Bloomsbury campus or online on Zoom. Book your place on Eventbrite and drop in any time between 12.30pm and 2pm.

In addition, Anthony Davis, the benefactor of the award, will be presenting his collection of fine bindings on Wednesday 19th July. He will talk about how he started collecting and show a selection of his book bindings, alongside bindings from UCL. This event is taking place in person at the UCL Bloomsbury campus. Book your place on Eventbrite and drop in any time between 12.30pm and 2pm.

We would like to thank all the applicants and wish them good luck and many years of joy in their future collecting. Our thanks also go to the judges for generously giving their time and, most of all, to the benefactor of the award, Anthony Davis, for helping nurture the collectors of the future with his encouragement, expertise and enthusiasm.

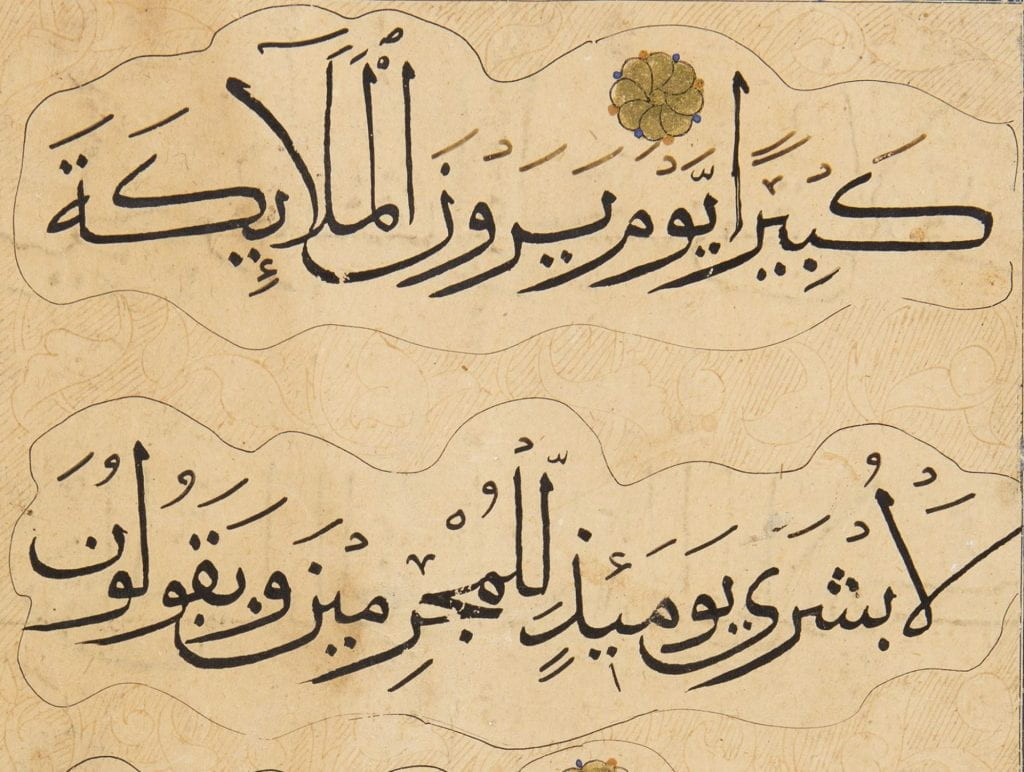

MS Mocatta 20: Taking a closer look at fragments of a 14th century Quran

By Sarah Pipkin, on 30 June 2023

Over the course of Spring 2023 we worked with our UCL Library Services’ colleague Abida S. to take a closer look at MS Mocatta 20: Fragments from the Holy Quran.

I am grateful to have been given this opportunity to take part in a fun project with UCL’s Special Collections team to showcase a 14th century Quran manuscript on the library social media account. The Quran is the holy book for Muslims. To be able to witness first- hand a Quran manuscript from the 14th Century was a special moment. I had this overwhelming feeling of awe and fascination when viewing a piece of history that has been preserved so well for centuries and I was able to read this Quranic Arabic text that is written in an intricate “muhaqqaq” script. This is the same Quranic words that is read today, unchanged.

MS Mocatta 20. Photo by Abida S.

The Holy Quran is the sacred religious book of Islam. In Islam, the Quran is God communicating with mankind. Reciting the Quran is a religious duty for Muslims, especially during Ramadan. It allows you to connect with the Quran’s message and is a rewarding spiritual practice.