Researching East London in Special Collections

By Joanna C Baines, on 15 January 2026

This two-part mini series of blogposts was written by MA Public History student Olivia Huidobro, who spent the summer of 2025 working for Special Collections as a Research Assistant, finishing a two-years long project to investigate what material we look after relating to East London. Photos for these blogs were sourced by Chelsie Mok, Teaching and Collections Co-Ordinator. Thanks so much Olivia and Chelsie!

Answering seemingly straightforward questions about East London can be harder than one might think. Where is it? What is it? And when? Although the East End is likely to hold a place in the imaginary of Londoners and others alike, it certainly refers to a highly heterogenous space. I kept this in mind when I started with the ambitious task of researching UCL’s Special Collections looking to identify East London material. What I hadn’t anticipated was just how rich a local history would appear, one deeply shaped by the spaces, communities, and industries across this part of the city.

In Beyond the Tower: A History of East London, John Marriott describes the emergence of East London as a distinct area in the 18th century. Precisely when London was becoming a metropolis, the East End became the manufacturing and commercial heart of it, drawing people from abroad with the promise of new opportunities, and acting as a place of refuge for those displaced. By the late 19th century, however, “the whole of East London was in the minds of many middle-class inhabitants as remote and inaccessible as the far corners of the empire”1. By finding material in the Collections that is related to the area, this project sought to explore and reflect on that complex, diverse, and often misrepresented history. As the UCL East campus approaches its third anniversary, having a selection of these items available for teaching will offer the possibility to promote a local object-based approach to learning.

East London limits have been intensely contested. Charles Booth’s mapping placed it between the City wall and the River Lea, while Walter Besant broadly defined it as everything east of Bishopsgate and north of the Thames. In contrast to the latter’s diffuse definition, which represented the perception of outsiders unfamiliar with the area, Millicent Rose suggested delineating East London in detail, bounded by Aldgate in the west, the Lea in the east, the Thames to the south, and Clapton Common to the north.

For the execution of this project, the geographical focus included the boroughs of Barking and Dagenham, Hackney, Havering, Newham, Redbridge, Tower Hamlets and Waltham Forest. The time scope, on the other hand, was actually shaped by the collection itself, and by the dates of materials that began to surface during the research – spanning from the 17th century to our present day.

I was lucky to join the project after it had started, so a lot of groundwork had already been done by previous contributors. For example, they had done impressive work identifying relevant information in secondary literature to help develop a list of keywords, and had even started executing some of the searches based on those keywords.

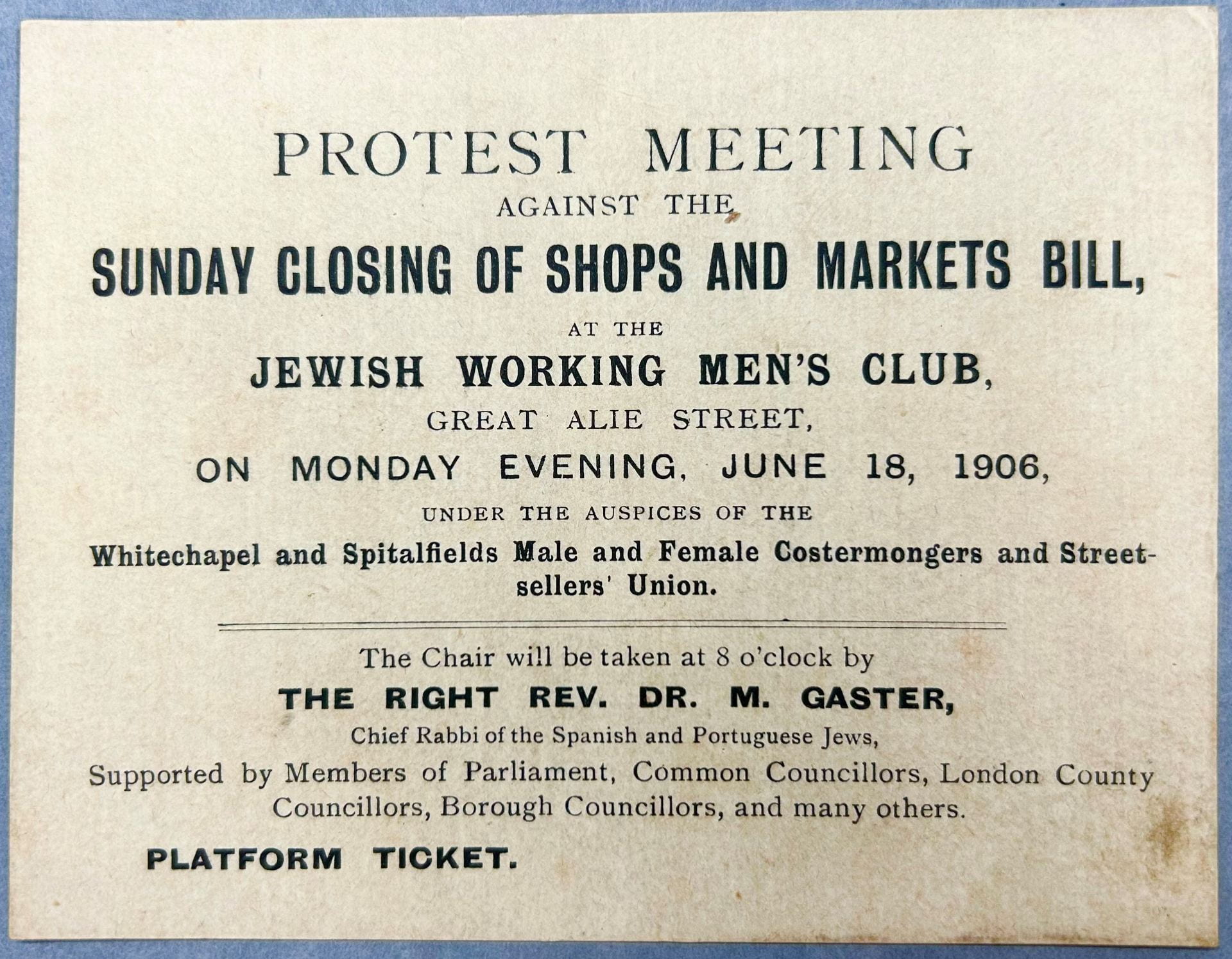

The search list, a key resource that acted as a guideline for my work, was subdivided into four categories: People, Groups, Companies & Industries, and Places related to the area. East London’s history quickly began to take shape through these terms and the materials they uncovered. Prominent groups included the Quakers, the Huguenots, and Irish and Jewish communities, and industries such as brewing, furniture-making, and sugar refining.

The Places listed included not only names of neighbourhoods, but also theatres, synagogues, churches, hospitals, and docks, amongst others. Searching for specific sites like “Spitalfields”, for example, brought up printed material related to the presence of the Huguenot community, the silk weaving industry, clock-making, and the findings of archaeological excavations at the Spitalfields Market. Among the archival material, one of my favourite items were Gene Adams’ papers on the Spitalfields Projects. Carried out in the 1970s, this initiative aimed to raise the awareness of the area’s 18th century architecture which was being threatened by redevelopment. It also included a history trail and activities at the Geffrye Museum, a proposed Spitalfields street museum, and an exhibition of the area.

A black and white photo of an exhibition space in Spitalfields. (GA/4/1/5)

Another search I found especially interesting, particularly for what it revealed about the area’s communities, was “Stepney”. The results included a book on the Stepney Jewish Girls’ Club, the marriage registers from St. Dunstan’s, an 18th-century volume about the Stepney Society (an early local charity), and a photograph of a home economics class at Stepney Green School. These items came from a range of collections, including the London History Collection, the Hebrew and Jewish Collection, and the Papers of Brenda Francis.

A black and white photo depicting home economics classroom scene at Stepney Green School in the 1970s. (BF/1/1/30)

Cover page of ‘The Rules and orders of the Stepney Society’. (London History 1759 RUL)

The initial names in the People list, however, fell short in reflecting East London’s diversity. Most of these had been selected from published secondary literature and were, unsurprisingly, white men. It was also not always clear who the name on the list was referring to. To address this, we developed a curated directory featuring the biographies of both men and women connected to East London, which also informed the project with topics and movements relevant to the area’s history. Although after looking at the catalogues I realised that the Collections didn’t always have material related to the people listed, the resource may remain as a reference of a more diverse set of stories of the lives within the area.

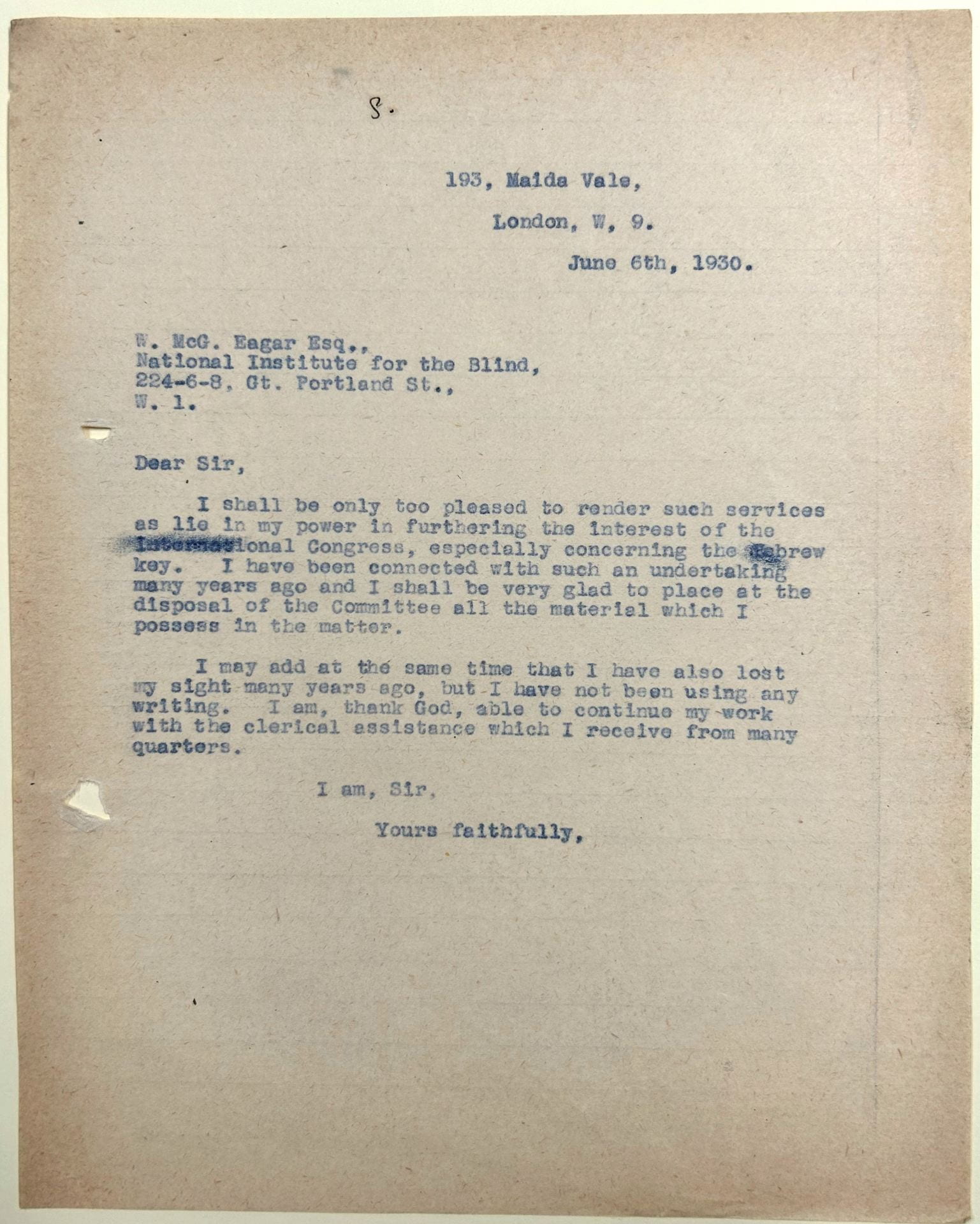

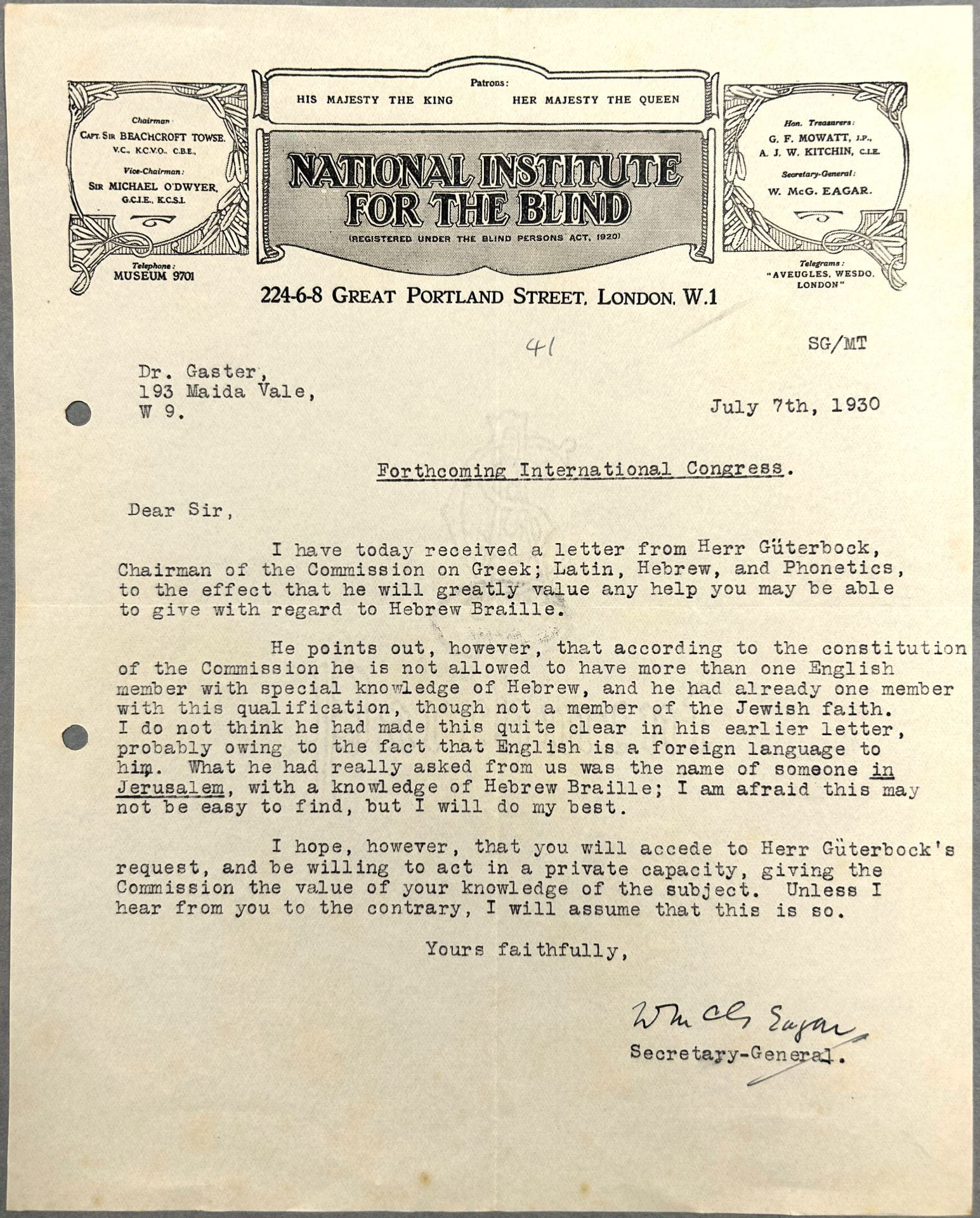

My research then continued with the aim of highlighting significant women who had lived or worked in East London. At this stage, I broadened my sources beyond academic journals to include digital and collaborative platforms like Wikipedia and the East End Women’s Museum. One of the most compelling discoveries was East London’s strong activist heritage, shaped by progressive groups campaigning for the rights of workers, women, and local communities. I was particularly drawn to the networks surrounding socialist figures, which came into focus through organisations such as the Dockers’ Union, the Women’s Trade Union League, the Independent Labour Party, and the East London Federation of Suffragettes, among others.

Towards the end of the project, the list compiling all of the East London material in the collections reached over 1,400 items. Within this extensive compilation is also reflected the outreach, diversity and the layered histories within the area itself. As a result, we also decided to create a narrower list, which included only the most relevant items while still enabling us to explore a wide range of topics, including education, feminism, workers’ rights, public health, crime, navigation, city planning, the silk industry, and many, many more.

Although this stage of the research project has concluded, its outcomes are still to come. The findings could support future teaching initiatives and help shape a dedicated subject guide on London, making it easier for students, researchers, and the wider public to discover the city’s stories through the university’s Special Collections. Ultimately, the project not only helped to map material and relevant themes of East London history, but also evidenced the capacity of collections to prompt new questions, build connections, and offer different perspectives on familiar places.

Bibliography

Marriott, John. Beyond the Tower: A History of East London. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vkwsx.

Close

Close