Researching East London in Special Collections: Lives of East London

By Joanna C Baines, on 16 January 2026

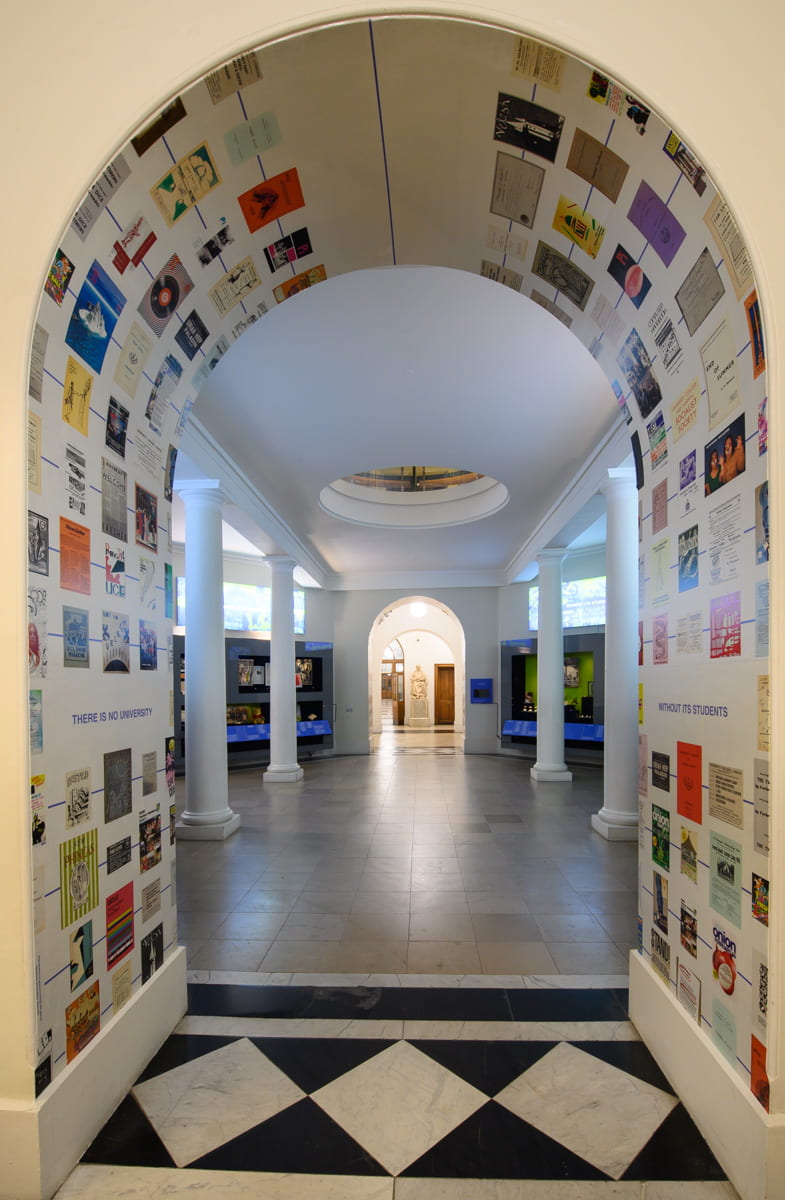

This two-part mini series of blogposts was written by MA Public History student Olivia Huidobro, who spent the summer of 2025 working for Special Collections as a Research Assistant. Photos for these blogs were sourced by Chelsie Mok, Teaching and Collections Co-Ordinator. Thanks so much Olivia and Chelsie!

During the summer, I have been researching UCL’s Special Collections to uncover printed and archival materials related to East London. Realising that perhaps the most important part of any place is its people, I focused on investigating East Londoners and their stories.

Following are the lives of three very different figures connected to the area and its heritage across centuries. Through material in the collections, these persons come into focus, not only through their biographies, but also as lenses onto social movements, cultural identities, and the broader historical processes that have shaped East London’s communities. From an activist involved in one of the most famous labour strikes of the 19th century, to a Jewish writer and community member, to a controversial figure of the East India Company, their stories reveal the diversity and contradictions of East London’s past.

Annie Besant and the Match Girls’ Strike of 1888

Annie Besant, born in 1847, was one of the figures I encountered during my research. Although she was neither born nor based in East London – as was the case for many of other social reformers or social workers of the time – she became involved with the area through her left-wing politics and her activism around the organisation of unskilled workers. Besant was a socialist, theosophist, freemason, educationist, and a campaigner for women’s rights, Irish Home Rule, and Indian nationalism.

By the mid-19th century, one of Bow’s best-known industries was match making – in particular, at the Bryant and May factories in Fairfield Works. Women and girls represented the majority of the workforce, responsible for removing matches from frames and boxing them. In 1888, while working as editor of The Link, the Law and Liberty League journal, Besant published an article criticising the poor working conditions and low wages provided by the company. In response, Bryant and May attempted to retaliate by dismissing three women they thought were whistle-blowers and therefore ‘trouble-makers’. This act would then spark a mass walkout, with around 1,400 match women and girls going on strike. Within days, Bryant and May decided to settle, re-hiring the fired workers, and promised to cease unfair deductions from pay and other improvements to their working conditions.

Cover of Match Making / by Walter Lucas (FLS Rare Pamphlets E39)

The Making of the Match Box section from Match Making (FLS Rare Pamphlets E39)

The strike was successful because of the determination and organising efforts of the young working women themselves, although Besant’s role contributed to the efforts and was relevant in raising a strike fund, building support within the community, and ultimately leading the formation of the match girls’ union on July 27th, 1888 – the first for women only. The following year, Besant won the Tower Hamlets seat on the London School Board running on a socialist platform, and also emerged as a key figure in the growing ‘New Unionism’ movement.

Finding material about her in UCL’s Special Collections was genuinely exciting: I came across an 1889 copy of the Fabian Essays in Socialism, to which she contributed alongside figures like George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb, as well as archival documents including her own letters to Karl Pearson, discussing feminism and political activism.

Letters from Annie Besant to Karl Pearson (PEARSON/1/6/4)

Grace Aguilar and the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish Congregation

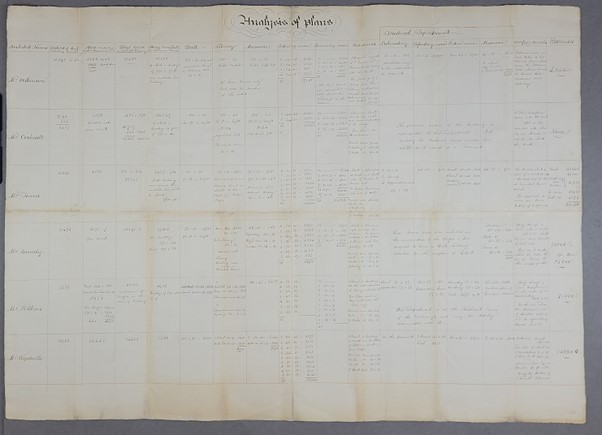

Grace Aguilar was born in Hackney in 1816 to a family of Sephardic Jewish refugees from Portugal. She was a novelist and poet, who brought Jewish subjects to the spotlight. Writing for a popular readership, she defended Judaism and argued for religious tolerance. Also, she specially addressed female readers with The Women of Israel (1845), a book of essays on Old Testament heroines. A first edition of this text is held within the Collections. Another particularly interesting find was a set of her papers, dated from 1831 to 1853, which included her manuscript notebooks as well as manuscript material in other hands – such as a book of tributes to Aguilar, a description of her last illness, and an account for the administration of her estate. These can certainly be a rich and underexplored resource for understanding the literary, religious, and cultural life of East London’s Jewish community in the 19th century.

The Women of Israel by Grace Aguilar (SR MOCATTA PAMPHLETS BOX 1)

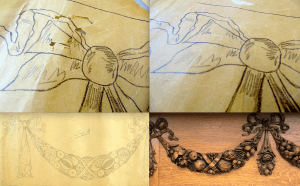

She and her family were active members of the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish congregation in London, which I discovered to be prominently featured in the Special Collections and thus discovering its significance for the area’s history. I was struck by the wealth of material showing up for searches like the ‘Bevis Marks Synagogue’, especially within the Mocatta Collection and the Gaster Papers. I enjoyed browsing through ephemera items, like visiting cards, greeting cards, cards of thanks and condolence, invitations, menus, place cards, table plans and guest lists, dance cards, programmes, orders of service, postcards, announcements, tickets, membership cards, price lists, forms, library slips, calendars, and pressed flowers. These small, everyday objects offer a glimpse into the community’s relationships, venues, fashions, meals, and other subtle patterns of cultural life. Many of these items are digitised and can be accessed here.

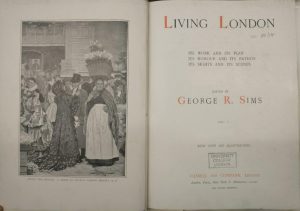

Josiah Child and the East India Company

East London is also entangled with darker aspects of British history. Josiah Child, born in 1630, was an economist, politician, and merchant who lived in Wanstead until 1673, when he purchased Wanstead Abbey in Epping Forest. He was involved with joint-stock companies from the early 1670s, an investor in the slave trade, and one of the founders and presidents of the Royal African Company. However, his primary focus was the East India Company, which is historically linked to East London, especially through its promotion of the East India Docks on the Isle of Dogs and the bustling trade that passed through them. Child served on the Company’s court and held positions as both deputy governor and governor, gaining powerful enemies and drawing widespread criticism along the way.

In response to this opposition, he published a number of treatises, copies of which can be found in the Special Collections. One of them is titled “The great honour and advantage of the East-India trade to the kingdom”. The other one takes the argument further, arguing that “the East-India trade is the most national of all foreign trades”, that “the clamors, aspersions, and objections made against the present East-India Company, are sinister, selfish, or groundless”, and that “the East-India trade is more profitable and necessary to the Kingdom of England, than to any other kingdom or nation in Europe”. Dating from the last decades of the 1600s, the possibility to access these texts is an incredible resource to think about the history of colonialism, empire and trade, and the public opinion and discourse around it.

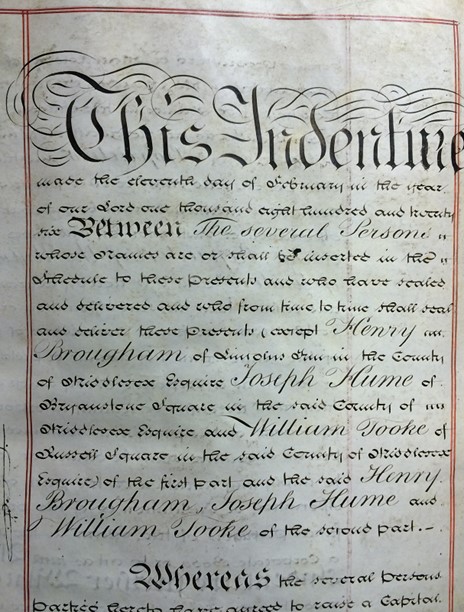

That the East-India Trade is the most National of all Foreign Trades from A Treatise wherein is Demonstrated (STRONG ROOM E 610 C34/1)

The Company also played a prominent role in slavery, beginning to use enslaved labour and transport enslaved people as early as the 1620s, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica. With the aim of mapping the material available on this issue and identifying resources for further study, I began the search for these difficult and often painful findings. The Collections seem to offer a wide-ranging view of the public discussions of the time and their political repercussions – covering issues like the Slave Registration Acts, the Slave Trade Act, the Abolition Act, and the wider anti-slavery movement. It is also relevant to consider the collections involved when finding this material: while most of the texts come from the Hume and Ogden Libraries, a few books belonged to Francis Galton’s library, bringing insights not only through their content but also through their context.

One last archival material I would like to highlight are the Jamaican Plantation Records – a small number of records from the sugar plantations of Buff Bay River Estate and Fearon’s Place in Jamaica, which include details of enslaved individuals and are incredibly rare. This collection was donated to the UCL Centre for the Study of Legacies of British Slavery in 2020, and was passed to UCL Special Collections in 2023.

By visiting these lives and legacies, we can access some of East London’s social struggles, its cultural diversity, and the entanglements with global commerce and empire. The items that form part of UCL’s Special Collections help illuminate their stories, while also revealing broader historical processes – like the area’s activism, community identities, and colonial trade and slavery. All of these have shaped East London’s heritage and continue to influence its character today.

Bibliography

Grassby, Richard. “Child, Sir Josiah, first baronet (bap. 1631, d. 1699), economic writer and merchant.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 September 2004. Accessed 22 July 2025. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-5290.

Satre, Lowell J. “After the Match Girls’ Strike: Bryant and May in the 1890s.” Victorian Studies 26, no. 1 (1982): 7–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3827491.

Taylor, Anne. “Besant [née Wood], Annie (1847–1933), theosophist and politician in India.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 September 2004. Accessed 22 July 2025. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-30735.

Valman, Nadia. “Aguilar, Grace (1816–1847), writer on Jewish history and religion and novelist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 September 2004. Accessed 22 July 2025. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-217.

“Annie Besant.” Wikipedia. Accessed 22 July 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annie_Besant.

“East India Company.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Last updated July 15, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/topic/East-India-Company.

“Grace Aguilar.” Wikipedia (Spanish). Accessed 22 July 2025. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grace_Aguilar.

“Matchgirls’ Strike.” Wikipedia. Accessed 22 July 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matchgirls%27_strike.

“Match Girls’ Strike.” English Heritage. Accessed 22 July 2025. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/match-girls-strike/.

Close

Close