What’s in a Textbook? Exploring the IOE’s Special Collections

By Nazlin Bhimani, on 12 December 2025

Earlier this week, I had the opportunity to introduce the IOE Library’s Special Collections to visitors from the Royal Historical Society, colleagues from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and members of the Institute. In this short presentation, I focused on showcasing the collections I most often use in my teaching, which also informs the historical inquiry work I do with doctoral researchers. This post expands on that introduction, and draws attention to some of the research outcomes that have emerged from scholars using these collections.

The Institute was founded in 1902 as the London Day Training College and became the Institute of Education in 1932, by which time it was regarded as the Empire’s most important educational institution. The library began with just a few books in the Principal’s office, and as the Institute expanded, these collections grew into a recognised flagship collection, one that supports teaching and research and is of national and international significance. The Special Collections, which evolved from the Institute’s working library and expanded through generous donations over the years, are actively used by staff, students and independent researchers from around the world.

But what unites the diverse holdings of the IOE Special Collections? A deceptively simple object: the textbook. As John Issitt (2004) notes, textbooks are ‘vehicles of pedagogy’ that contain the ‘received knowledge’ of their time, yet they are often dismissed as having little intrinsic value. Textbooks are, in fact, rich cultural artefacts. They reveal not only what was taught in schools, but also how teachers were trained, which knowledge was valued, the ideologies shaping generations of teachers and learners, and where silences appear. Thus, far from being neutral transmitters of facts, they reveal changing teaching methods, social and political priorities, prevailing attitudes towards class, race and gender, and provide insights into everyday life. A key figure in recognising textbooks as worthy objects of scholarly inquiry was Ian Michael, Deputy Director of the IOE in 1973. He established the Textbook Colloquium and founded the journal Paradigm, legitimising textbook research in the 1980s as a recognised area of study. His personal library now forms part of the Special Collections.

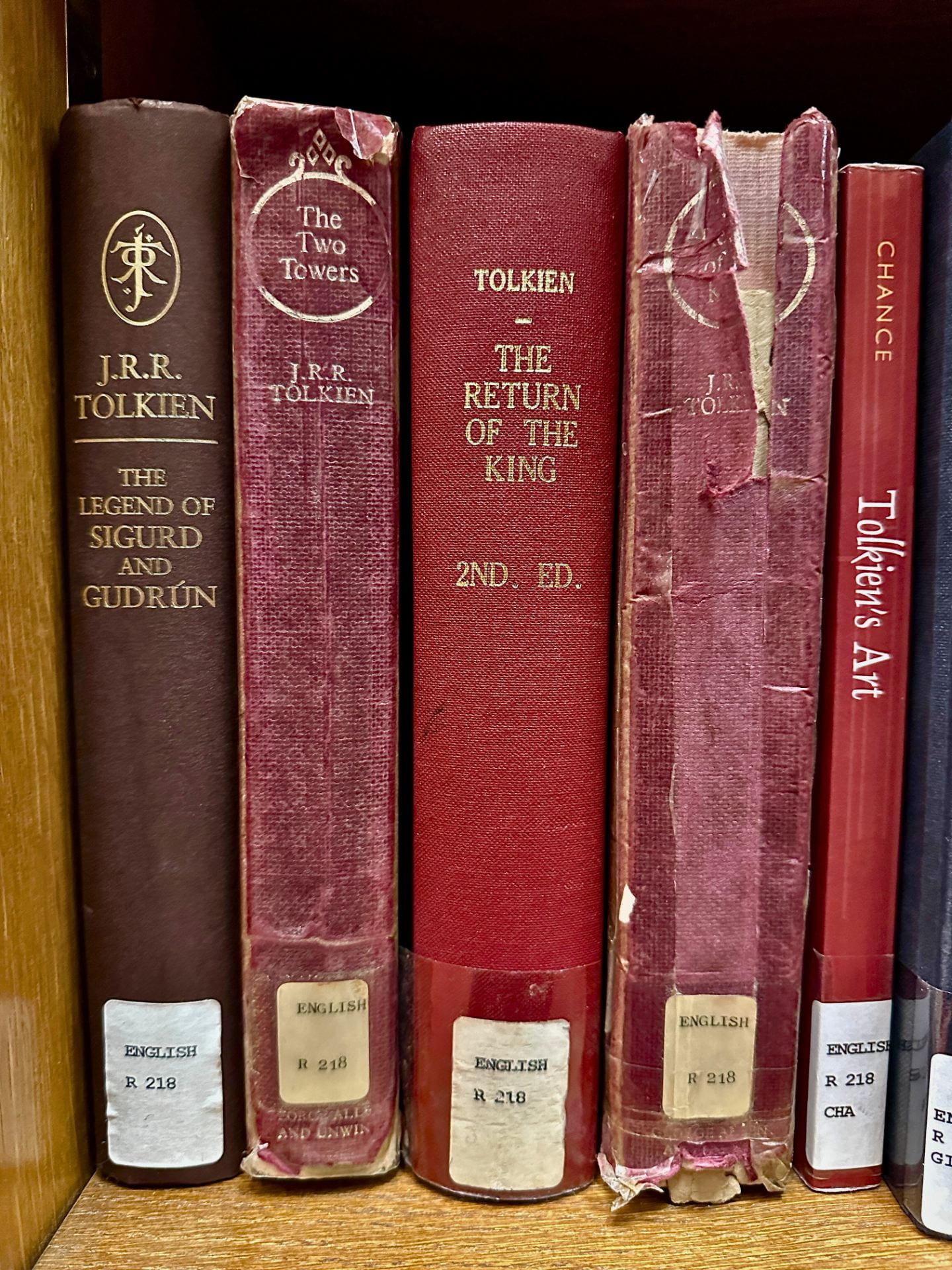

One of the collections that most clearly illustrates the significance of textbook research is the Historical Textbooks Collection. It grew out of the National Textbooks Research Library, established in the 1960s to allow teachers to browse materials before purchasing for their schools. It includes a wide range of school textbooks spanning all subjects and levels until the introduction of the National Curriculum. History and geography textbooks, the latter forming a discrete collection, demonstrate how Empire and colonised peoples were portrayed in educational materials. The collection also reflects pedagogical developments over time, from rote learning to more differentiated and child-centred approaches, and offers insights into the history of publishing and school material culture.

The History of Education Collection adds further depth, containing textbooks used for teacher training, including works by early educational thinkers such as John Locke and John Dewey, as well as texts produced by the Institute’s own principals and directors. The collection also includes teachers’ manuals and handbooks, including those by the prolific children’s author Enid Blyton, whose works were frequently endorsed by the Institute’s second director, T. Percy Nunn, as they shared the same educational ideals. These manuals not only provide insight into classroom methods, but also reflect the growing standardisation of teaching practice. This standardisation was part of the wider move towards professionalising teaching. In addition, the collection has some historic gems, including the first illustrated children’s book, Orbis Pictus by the Moravian educator, John Amos Comenius, published in 1658, and the 1740 edition of Dilworth’s A New Guide to the English Tongue, one of the most widely used textbooks of its day. It is referenced in Charles Dickens’s Sketches by Boz, and is said to have helped Abraham Lincoln learn to read.

Textbooks also appear throughout our subject-specific collections. The Rainbow Collection focuses on music education, whilst the Baines Collection contains 18th and 19th-century children’s books and encyclopaedias. Our various Comparative and International education collections reveal how pedagogical ideas travelled between nations, reflecting in particular the institution’s wider influence on colonial education. The personal libraries of His Majesty’s Inspectors (HMIs) are particularly revealing, illustrating the intersections of pedagogy and policy. For example, HMI Captain Grenfell’s collection on physical education anticipated the subject’s compulsory status amid concerns about national efficiency, whilst HMI F. H. Hayward’s materials on moral education and responsible citizenship reveal links with the Eugenics Education Society, which sought to promote ‘moral hygiene’ or sex education, steering youth away from vice and toward ‘fit’ marriage partners.

Beyond print, we have the BBC Broadcasts for Schools (1926 to 1979), which by 1930 were used in approximately 5,000 schools. The ‘wireless lessons’ were, in essence, ‘textbooks of the air’, and they pioneered audio and then audio-visual learning. These broadcasts had a sustained influence on education for fifty years, teaching children ‘Received Pronunciation’, promoting aesthetics education and reinforcing British cultural heritage. Connected to all of these collections is the School Examination Papers Collection, which dates back to the late nineteenth century. It represents educational policy and practice, linking the textbook to the broader question of what was deemed worth knowing and assessing.

Then we have the 1960s MACOS (Man: A Course of Study) Collection, which exemplifies ongoing transnational influences in education. This multimedia social studies curriculum attempted to teach cultural diversity through studying the Netsilik Inuit and was adopted in schools across the United States and Britain. However, it faced intense conservative and religious opposition, which ultimately led to funding cuts and the programme’s decline in 1975. The ILEA Collection of publications tells a parallel story. This progressive education authority, active from the 1960s, produced materials that were often controversial, particularly around issues of race and sexuality. The authority was abolished by the Conservative government in 1990.

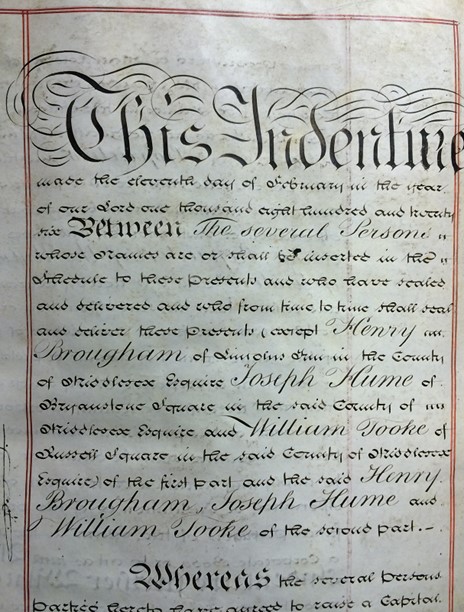

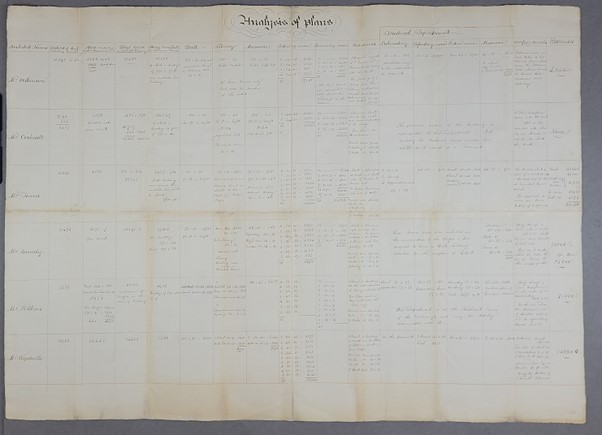

These collections are far from static. They actively support teaching, research, and curatorial work across UCL and beyond, with students and researchers engaging with original materials in ways that develop critical analytical skills while uncovering new historical insights. Funded research projects, such as the ‘Literacy Attainment’ study (now published as a monograph by Professor Gemma Moss), as well as the ongoing work on the Empire, Migration and Belonging project, illustrate the breadth of scholarly engagement. Students have explored constructions of class, gender, and race, conducting close textual analysis to trace how social hierarchies were naturalised through everyday classroom materials. For example, one student examined illustrations in a textbook to reveal how Chinese people were visually portrayed, showing that racial stereotyping was embedded in educational resources. Her work will appear in Paper Trails, the BOOC published by UCL Press. Beyond the IOE, other historians, including independent scholars, often consult the IOE’s collections, sometimes in conjunction with materials from the IOE’s archives. A recent example is the 2024 publication by independent researcher Daniel O’Neill, whose book This Excellent Man: Derbyshire Architect G. H. Widdows and English School Design, 1904-1936, draws extensively on both rare books and archival collections, making a significant contribution to our understanding of pedagogy and school architecture.

The IOE’s Special Collections — and I have only touched the tip of the iceberg among the catalogued collections — remain invaluable for studying how knowledge has been constructed, transmitted and contested. They document not just what was taught, but the ideological frameworks that shaped education, the networks through which pedagogical ideas circulated, and the evolution of teaching practices across centuries. The seemingly simple textbook opens complex questions about power, knowledge, and whose voices were centred or silenced. As we continue to catalogue, preserve, and make these materials accessible, we invite researchers to engage critically with this history to understand not just what education was, but what it might become.

We would also like to invite researchers to respond to our call for papers for a special issue of Paper Trails on ‘Difficult Collections’, or to consider applying for one of our Research Institute for Collections Visiting Fellowships. These opportunities offer a chance to engage directly with our rich historical collections.

Close

Close

![[Image and Transcription of Receipt for Donation made by Gaster (file 131, item 44)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2918-1024x652.jpg)

![Image of S. Edelstein’s 21 March 1899 Mostly Hebrew Postcard to Gaster (file 117, item 9)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2919-238x300.jpg)

![[S. Edelstein’s 24 March 1899 Romanian Postcard to Gaster (file 117, item 20)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2920-1024x799.jpg)

![Image of Personal Letter of Gratitude to Gaster, Accompanied by a Wedding Invitation (file 131, item 58)]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2023/09/IMG_2932-893x1024.jpg)