Kelmscott School historians present a History of London – a digital exhibition with Special Collections

By Anna R Fineman, on 31 January 2023

Kelmscott School students viewing William Faden’s map of the River Thames and surrounds (1799) from UCL Special Collections, at One Pool Street, UCL East.

Last term the Outreach team of UCL Special Collections were delighted to collaborate with Year 9 History enthusiasts at Kelmscott School in Waltham Forest. The club, called Becoming an Historian, took place over six weekly after-school sessions. Students defined the skills and qualities which make a good historian, learnt how to undertake historical research of primary resources, and each explored an item from UCL Special Collections in-depth. They chose the History of London as their theme and have produced informative and dynamic museum labels presented in this mini digital exhibition. You can also read their personal responses to the collection items on Twitter. The students each gained different things from participating in the club, as these three examples attest:

My favourite thing about the club is the amount of discussion we have. An opportunity to speak out your thoughts freely was very encouraging.

I liked getting to know more about how research is conducted.

My favourite thing about the club was the opportunity to work with others on a subject that I am passionate about.

To conclude the club, the students came to visit UCL East on 30 January 2023 – the very first school group through the doors of One Pool Street! Supported by the Outreach team, the students were thrilled to experience the original historical items they had been researching – having worked from facsimiles until that point. One student observed:

‘It was interesting to see the details on the real-life item, as it was much more intricate than online.’

While another commented:

‘I was surprised seeing the actual item and the actual text. It was great!’

UCL Special Collections say a huge thank you to the students for undertaking this research and for helping to tell the stories of these extraordinary rare books and archives in our care.

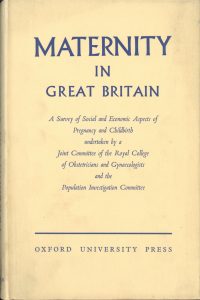

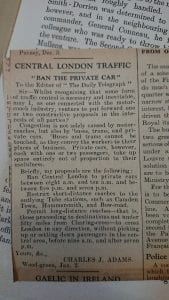

Living London, Volume 1, Ed. George R. Sims (1902)

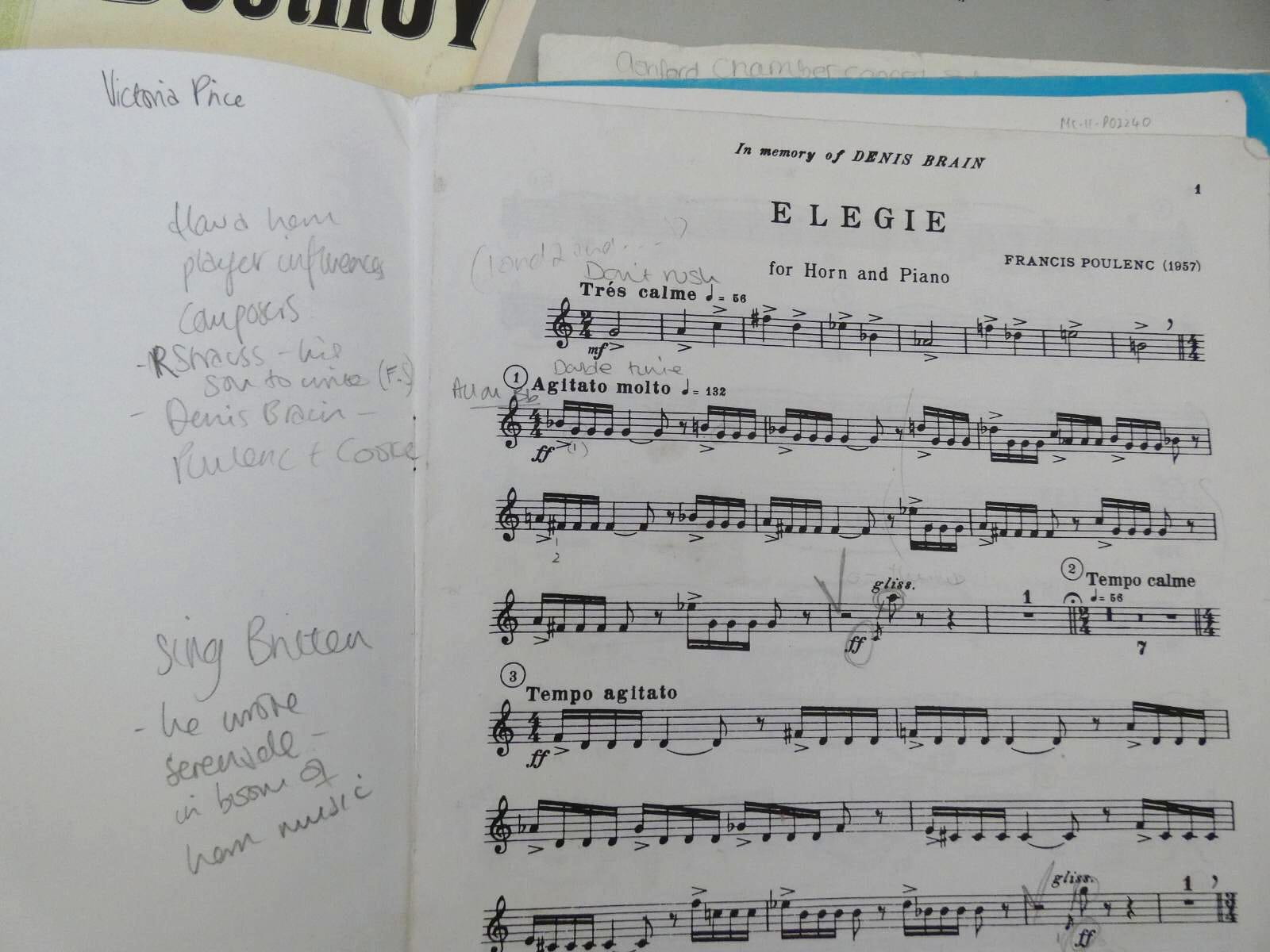

A double page spread of the rare book Living London by George R. Sims (1902).

Living London was written in 1902 by George R. Sims. It describes scenes of people looking for work in the London Docklands. At the time of writing, Britain was plagued by a deep class divide; upper classes saw themselves as superior to the working class. The mixing of different classes was frowned upon. Sims himself was the son of a successful merchant. Through the medium of the book Sims disparages those looking for work in the docks by describing them as ‘the common slum type, either criminal or loafer or both.’

Zahra

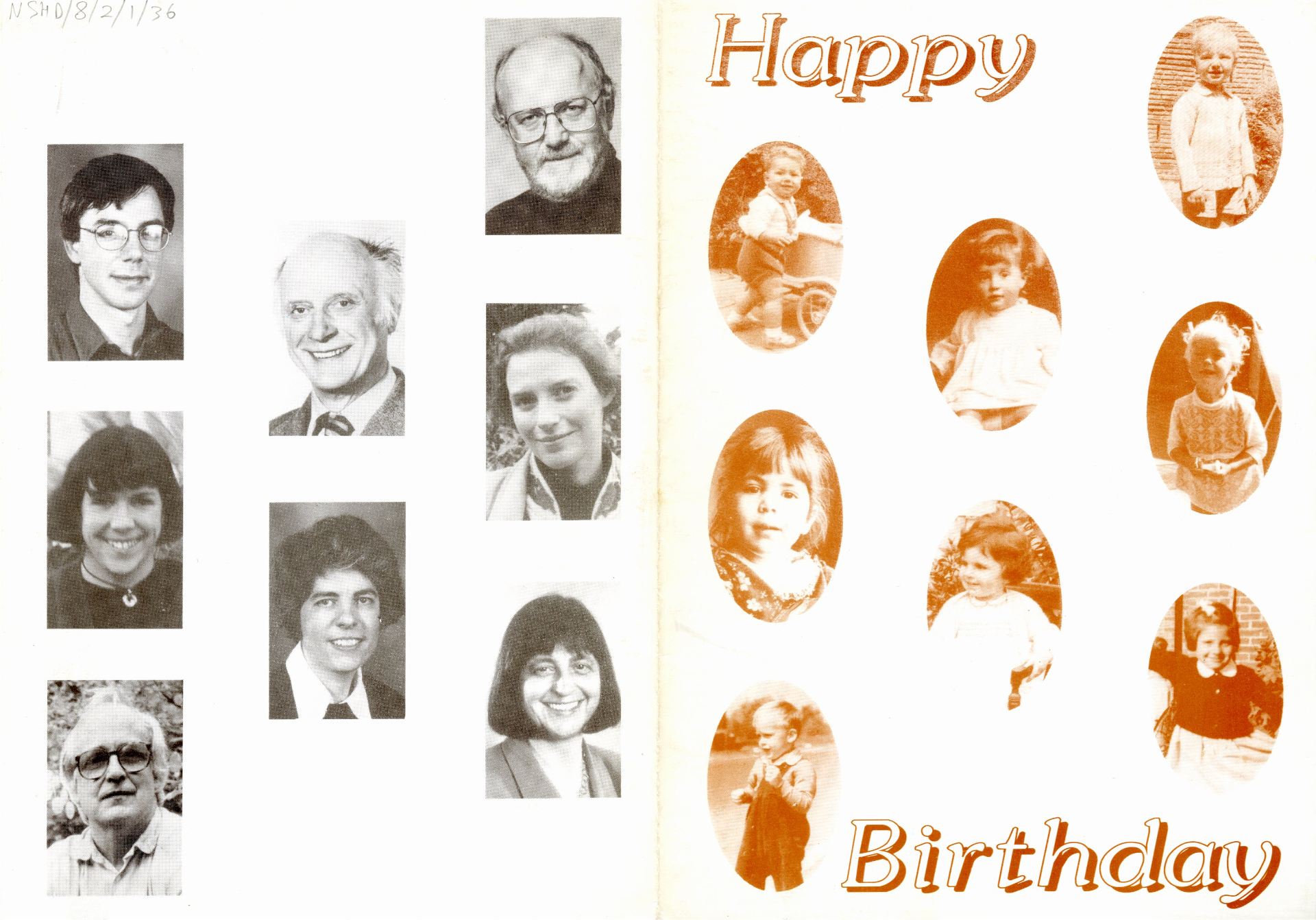

The several plans and drawings referred to in the second report from the select committee upon the improvement of the Port of London, illustrated by R. Metcalf, William Faden (1799)

A plan of the River Thames and surrounds, for ‘the improvement of the Port of London’, illustrated by R. Metcalf and published by William Faden (1799).

William Faden (1749-1836) was a British cartographer. He was so well known that he was the royal geographer for King George III. This meant that he had to publish and supply maps to the royals and parliament. The map shows a detailed view of London.

Musa

William Faden was a British cartographer and a publisher of maps. He was born on July 11 1749 and died on March 21 1836. He self-printed the North American Atlas in 1777 and it became the most important atlas chronicling the revolution’s battles. He also made this map of the River Thames which gives a lot of information about the way buildings were placed, and the trading docks that held the actual trading ships used back in the day.

Petar

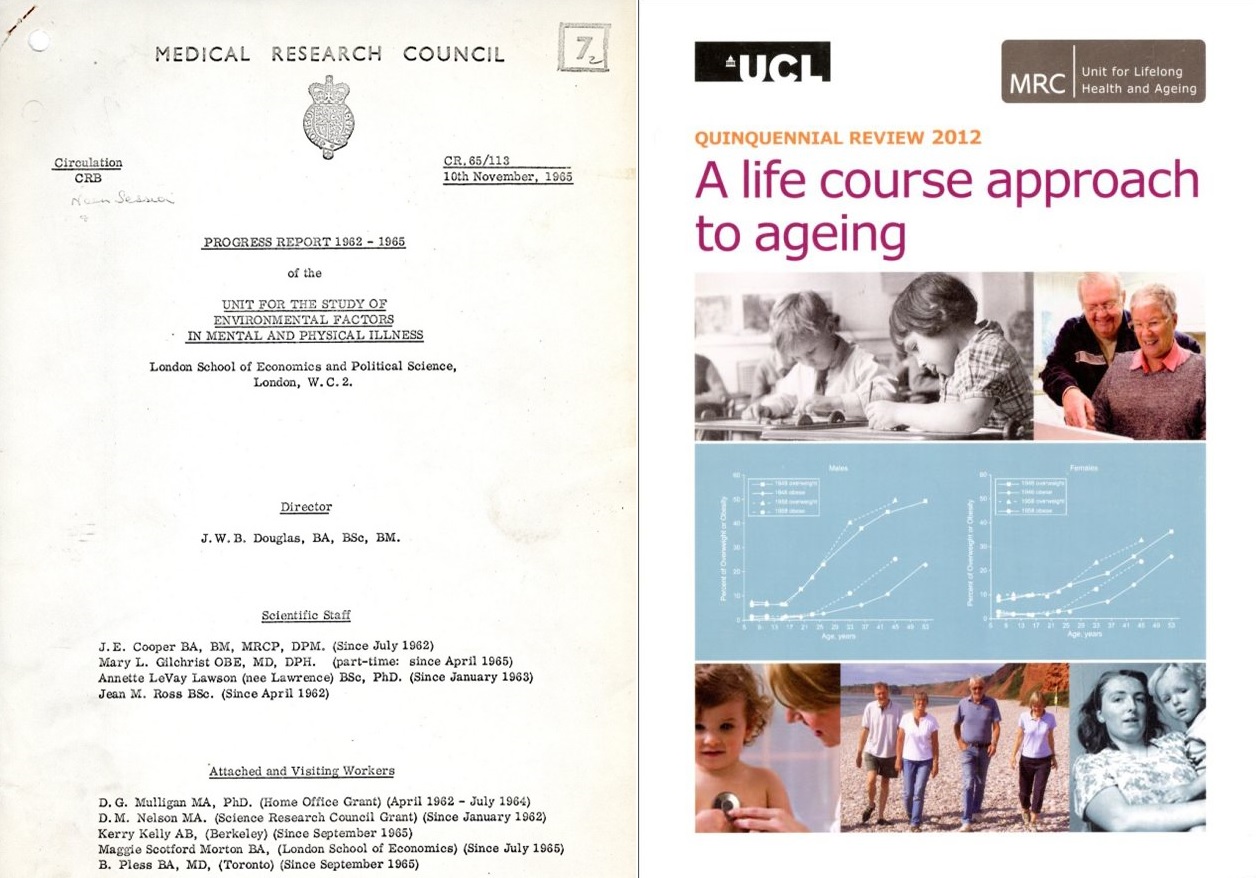

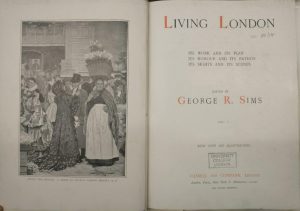

Letter from the Trades Advisory Council regarding wartime food regulations in relation to the baking of challah (1945)

The first page of a letter from the Trades Advisory Council regarding wartime food regulations in relation to the baking of challah (1945).

This letter by the Trades Advisory Council was drafted in the 1930s and reconstituted in the 1940s to prevent growing hostility towards the Jewish population from British fascists. In this letter it states that the Jewish challah loaf was very similar to the bun loaf, and would be placed in the same category as it. It goes on to state that the ingredients for it should be rationed for the best of the British people.

Ahrab

The Trades Advisory Council was created in the 1930s and reconstituted in 1940 to challenge the British fascists. Because the Jewish bread challah is extremely similar to bun loaf, which was rationed, the council decided to add it to the same category as the bun loaf, saying that every British citizen was to put the nation first.

Lu’Ay

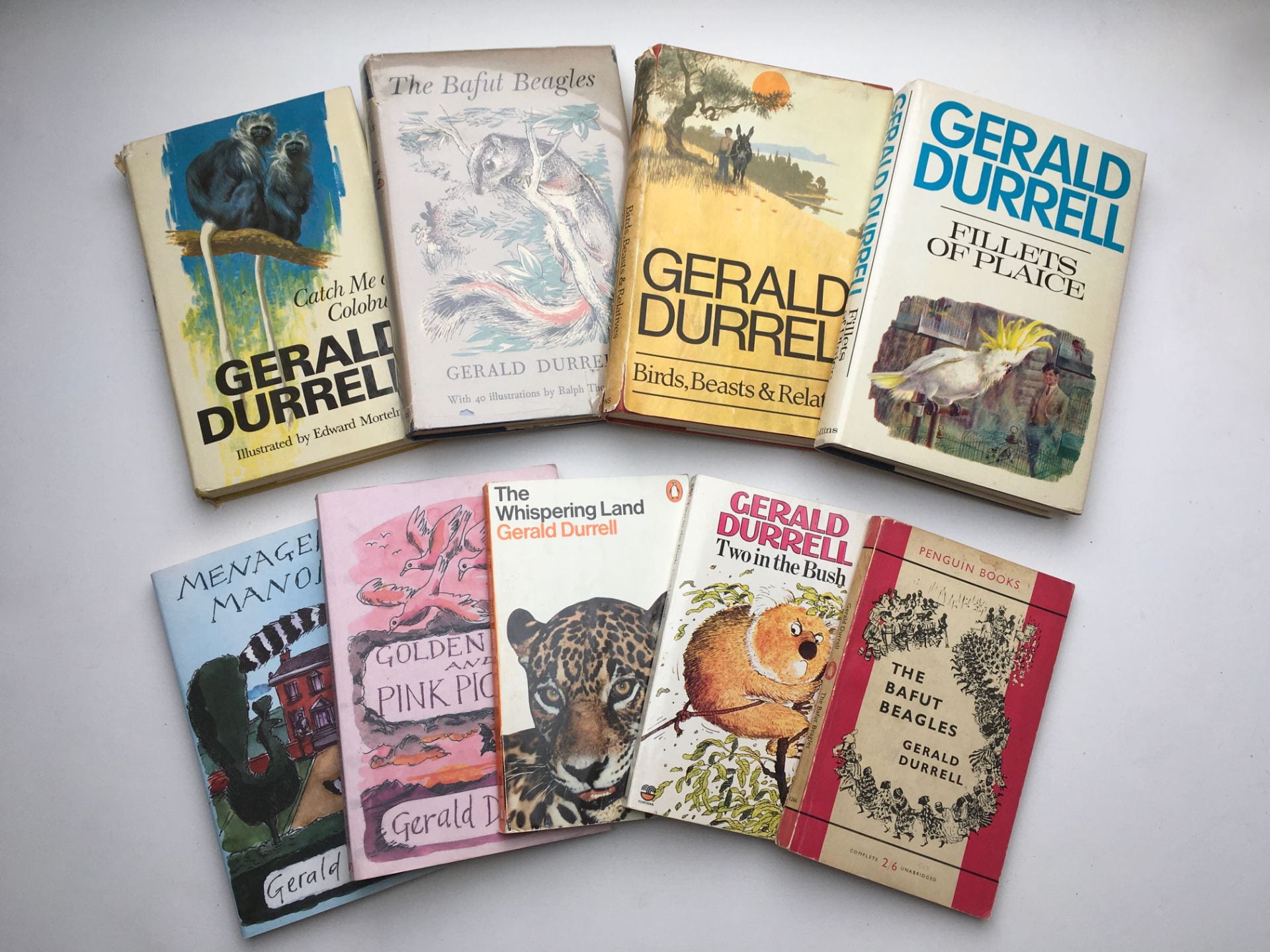

Vagabondiana : or, anecdotes of mendicant wanderers through the streets of London; with portraits of the most remarkable drawn from life, John Thomas Smith (1814)

An illustration of a woman, drawn from life on the streets of London, from Vagabondiana by John Thomas Smith (1814).

This is a book written and illustrated by John Thomas Smith. It was published in 1813 and made from paper with printings of paintings. The author was born in 1766 inside a Hackney carriage. He was educated at the Royal Academy and was nicknamed ‘Antiquity.’ He attempted to become an actor, and then a sculptor. His eventual occupations were engraver, draughtsman and curator.

Ace

Metropolitan Sewers: Preliminary report on the drainage of the metropolis, John Phillips (1849)

The first page of Metropolitan Sewers: Preliminary report on the drainage of the metropolis, by John Phillips (1849).

Due to a combination of growing population, lack of sanitation and sewage systems, a result in the capital was several severe, contagious outbreaks of sickness, like cholera and typhoid. London’s Metropolitan Commission Sewers was established in 1848 as part of the solution to the issue. This text of 1849 describes the necessity for construction. It has plans for the running of a new sewer tunnel west to east, to transport London’s waste. The tunnel wasn’t built, but this map depicts London as far as Stratford.

Faith

East London, Walter Besant (1901)

Illustration ‘The Hooligans’ from East London by Walter Besant, 1901.

‘The Hooligans’, a picture from Walter Besant’s book East London, showcases five figures, two armed, in a dark room with an arched entrance. One man seems to be lying down in pain, possibly from an injury caused by the two armed men. In a passage below the picture it is stated that ‘the blood is very restless at seventeen.’ This could be related back to London’s notoriously high knife crime and gang violence rate, with thousands of children taking part. Despite being published in 1901 East London mirrors modern London and its violent tendencies.

Natalie

What frightens me the most were ‘The Hooligans.’ Looking at the picture alone gives me the shivers. The beaten-up man lies defeated in the hands of the hooligans. These behaviours are similar in today’s knife crime London.

Habiba

This book was published in 1901, and it was written by Walter Besant. Besant was born on August 14 1836 and died on June 9 1901. He was an English novelist and philanthropist and who wrote quite a lot of works, one of them is East London. A good enough question is why did he write East London? Besant wanted to describe the social evil in London’s East End. And in my personal opinion, in this book he wanted to show people who lived in the west and in the south how people live in the east.

Kiril

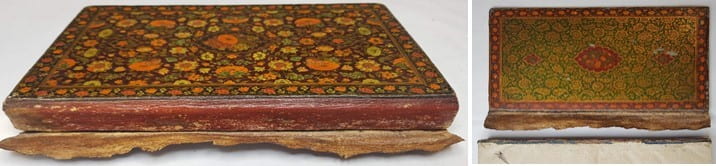

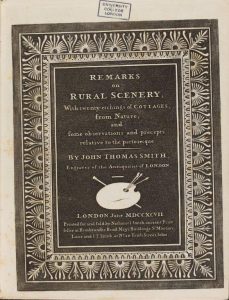

Remarks on rural scenery : with twenty etchings of cottages, from nature; and some observations and precepts relative to the pictoresque [sic], John Thomas Smith (1797)

The title page from Remarks on Rural Scenery by John Thomas Smith (1797).

The book Remarks on Rural Scenery was written in 1797 by John Thomas Smith, as the first of two items bound together. The author was also known as ‘Antiquity Smith’ and was born in 1766 in a Hackney carriage. When he left school he tried to become a sculptor, but left to study at the Royal Academy to become a painter, engraver and antiquarian. With this book he tried to bring to the mainstream the picturesque life in rural areas of England.

Viky

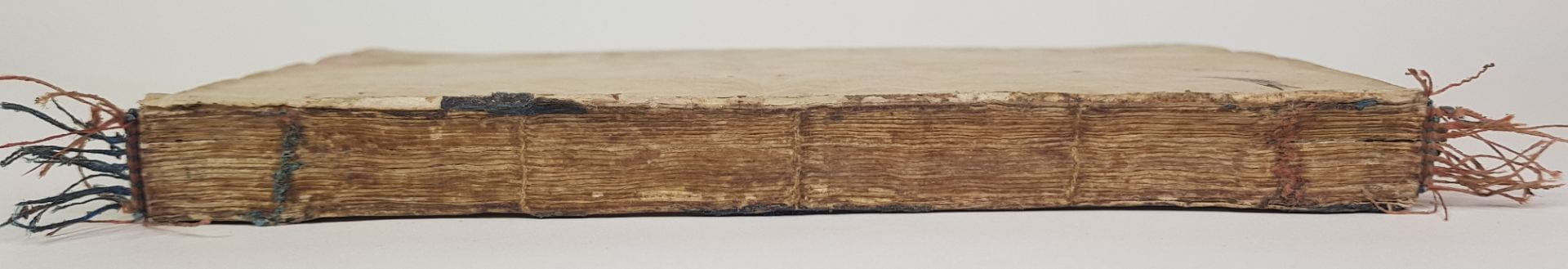

Common Lodging House Act, Metropolitan Police (1851)

The first page of the Common Lodging House Act by the Metropolitan Police (1851).

The industrial revolution contributed to the population growth in the nineteenth century. During the century a record number of people relocated to London. By the middle of the century areas where cheap lodging could be found grew dangerously congested. The least expensive types of lodging were common lodging houses, where residents shared rooms and frequently beds with multiple other residents. Under the 1851 Act, these homes were registered with Metropolitan Police. These regulations were a direct reaction to the inadequate conditions of crowded housing and unscrupulous landlords and recognised the risks to public health posed by disease and poor sanitation.

Maleah

The Common Lodging Housing Act, 1951, sometimes known as the Shaftesbury Act, is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is one of the principal British Housing Acts. It gave London boroughs the power to supervise public health regarding ‘common lodging houses’ for the poor and migratory people. This included fixing a maximum number of lodgers permitted to sleep in each house, promoting cleanliness and ventilation, providing inspection visits and ensuring segregation of the sexes. These powers were extended to local authorities in the Common Lodging Housing Act of 1851.

Malaeka and Inayah

Close

Close