This year, UCL Special Collections is hosting the Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize, to be awarded to a current student studying towards a degree at a London-based university. For many students, the label of ‘book collector’ is a grandiose one, and while the tiny space on their bed-side table may be crammed with text books and novels these don’t seem to match the image conjured up by the words ‘book collection’.

However, the Anthony Davis Prize does not require you to own first editions, or signed manuscripts, or books so old they are crumbling to dust. So if you’re interested in a £600 cash prize and a chance to talk about the books that you own and love, read on to learn how you can be a book collector – and then apply for the Prize.

You’re actually already a book collector

‘Collecting’ as a hobby is often seen as something for the rich, or the obsessed, or both. Whether it’s stamps or classic cars or Pokémon cards, the idea that a collection is prized for its rarity and monetary value above all else has become standard, as has the image of collectors as always collecting, always trying to one-up their rivals. This image is not untrue of every collector, but ignores the real reason many people collect: the love they have for their chosen collectable, and the joy they experience in finding something new to them, and sharing it with others. It ignores, too, that collections do not have to be rare and expensive to be enjoyed. It ignores that you probably, entirely unintentionally, already have a collection of your own.

If you’re a lover of books then you probably have a good number of them. They may not have been amassed with any particular purpose beyond reading them, but the pile of unread paperbacks on the floor next to your bed, the childhood favourites stacked on top of your wardrobe, and the romance novels stuffed in shoe boxes that you can’t quite bring yourself to give away are a collection of books. That makes you a book collector.

The first question is: what books are you collecting?

Turning your collection of books into a book collection

For the Anthony Davis Prize, it is not enough to own books. We’re asking that your collection ‘consists of no fewer than 8 printed and/or manuscript items reflecting a common theme, which the collector has deliberately assembled as the start of a collection and intends to grow’. So you’ll need to find a common theme among your book collection, one which you’d like to expand on as you buy more books.

A good place to begin is looking at subject, genre, or author. If you have an interest in baking cakes, you may have amassed a good number of food magazines. You may have a good collection of graphic novels. You might have every book written by J. K. Rowling.

Some book collections have links that are less obvious but perhaps more intriguing, and it might help to remember why you bought the book or were given it in the first place. Do you own more than one Booker Prize winning novel? Were you drawn to some of your books because of the art on the front cover? Did you at some point decide that you were going to read every book on Wikipedia’s list of ‘novels considered the greatest of all time’, or that you were going to focus on reading sci-fi written by BAME authors?

Once you’ve got a broad theme for your book collection, you may need to narrow it further. Think about the books you have and what links them together, what really appeals to you, or makes them different from the books that your friends have. It could be that you have a really good collection of manga, but your particular interest is magical girls, and most of your collection has been translated from Japanese into Spanish. Or your cookbooks are all written by 21st century TV chefs and focus on Italian cuisine. Or the book covers you are most drawn to in second hand book shops were all designed in the 1970’s. Or maybe your collection is very narrow indeed, consisting simply of different editions of exactly the same book, showing the different ways it has been published, marketed and interpreted through the years.

Once you’ve got a broad theme for your book collection, you may need to narrow it further. Think about the books you have and what links them together, what really appeals to you, or makes them different from the books that your friends have. It could be that you have a really good collection of manga, but your particular interest is magical girls, and most of your collection has been translated from Japanese into Spanish. Or your cookbooks are all written by 21st century TV chefs and focus on Italian cuisine. Or the book covers you are most drawn to in second hand book shops were all designed in the 1970’s. Or maybe your collection is very narrow indeed, consisting simply of different editions of exactly the same book, showing the different ways it has been published, marketed and interpreted through the years.

And voilà! You have your book collection. You should be able to describe it in a sentence – “I collect autobiographies of women who grew up in Northern Ireland during the Troubles”. But for the Anthony Davis Prize, the sentence needs to be a little longer. “I collect children’s picture books on space exploration because…”

Why is your book collection interesting?

Part of your application for the Prize will include ‘an essay of not more than 500 words explaining the coherence and interest of your collection, and why and how it was assembled’. ‘Interest’ in this case means not just why it’s of interest to you, but why it may be of interest to other people. Don’t panic – there’s a good chance that what is interesting to you is of interest to other people. Children’s picture books on space exploration are of interest to you because they show how we, as a society, view space as scary/exciting/a potential utopia. Northern Irish women’s autobiographies interest you because their voices are often missing in films/novels/school curricula.

So far I’ve mostly described the content of books as the reason for collecting them, but it’s worth noting here that it may be the physicality of a book collection that makes it interesting. If you’re someone who buys your books second-hand or loves browsing used-book stores, then you may find that you’re drawn to books that have been made or bound in a particular way. The history of individual books can also be intriguing – you may find you are interested in collecting books that have bookplates from past owners, or inscriptions from past gift-givers. In these cases, you’ll need to be able to explain why these bindings, these book plates, or these inscriptions are interesting.

It’s worth noting as well, that the Anthony Davis Prize is for ‘book collecting’ but isn’t only restricted to books – collections of sheet music, manuscripts, magazines, booklets and other ephemera are all admissible for the Prize. The selection of music here is from the collection of Vicky Price, Head of Outreach at UCL Special Collections, who has been collecting (and playing!) music for the French horn for over 20 years.

It’s worth noting as well, that the Anthony Davis Prize is for ‘book collecting’ but isn’t only restricted to books – collections of sheet music, manuscripts, magazines, booklets and other ephemera are all admissible for the Prize. The selection of music here is from the collection of Vicky Price, Head of Outreach at UCL Special Collections, who has been collecting (and playing!) music for the French horn for over 20 years.

Adding to your book collection

I made the point at the start of this post that book collecting does not need to be an expensive hobby. Unfortunately, it is seldom a completely free hobby either. If you are going to grow your collection (and the Anthony Davis Prize asks you to list five items you could realistically add to it) then you are going to need to spend some money. It does not, however, have to be a lot.

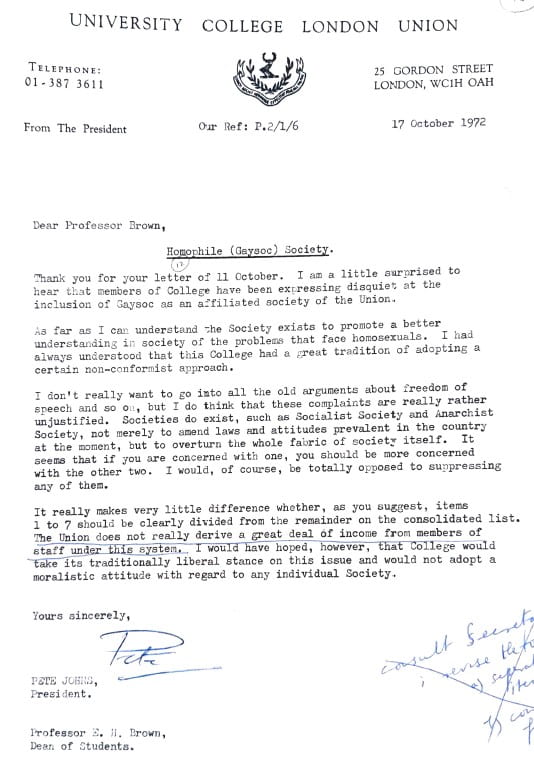

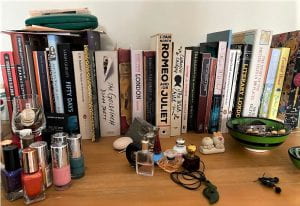

Here I’m speaking from experience. The adjacent image shows my own collection – books in the ‘Chalet School’ Series by Elinor M. Brent-Dyer, originally published between 1925 and 1970. If you click to enlarge the photo, you’ll see these books have a variety of different histories. Some of them I bought new, as recently republished books. Some of them came from scouring second-hand book shops, or visiting sales at public libraries (a great source of pre-loved books!). More relevantly for this time of lockdown and self-isolation, some came from purchasing used books through sites like Amazon, eBay, and the more specialist AbeBooks.

Here I’m speaking from experience. The adjacent image shows my own collection – books in the ‘Chalet School’ Series by Elinor M. Brent-Dyer, originally published between 1925 and 1970. If you click to enlarge the photo, you’ll see these books have a variety of different histories. Some of them I bought new, as recently republished books. Some of them came from scouring second-hand book shops, or visiting sales at public libraries (a great source of pre-loved books!). More relevantly for this time of lockdown and self-isolation, some came from purchasing used books through sites like Amazon, eBay, and the more specialist AbeBooks.

If my focus had been just on collecting first editions, then I could easily have been spending hundreds of pounds at a time to build this collection. Instead, my focus has always been on ‘completing’ it – that is, owning every title in the series – which often meant spending only a couple of pounds on a cheaply made paperback. But it has also meant finding undervalued hardbacks, with or without the dustjackets, which has always given me a nerdy thrill. And it has meant connecting online with other people who collect the series, swapping titles that I’ve doubled up on with titles that they don’t need.

What happens next

Putting the Prize to one side for the moment, what happens next to your collection is up to you. If you are like me, then the size of your collection will be limited by the size of your bedroom, flat or house. My Chalet School collection still resides with my parents, as I have less living space as an adult than I did as a teen, and I have to have a strict one-in-one-out policy with new book purchases (well, strictish).

But you may also find that, as time goes on, you have fewer limits, and your hobby grows into a passion. In contrast to the smaller collections I’ve discussed above, here’s one from UCL Special Collections’ Project Conservator, Laurent Cruveillier. His intent was to create a collection of cookbooks signed by their authors, and over 25 years he has put together a collection of over 500 books, from the 19th century to today. His collection is vast enough to include a sub-collection, of recipe booklets produced by American food and appliance companies.

But you may also find that, as time goes on, you have fewer limits, and your hobby grows into a passion. In contrast to the smaller collections I’ve discussed above, here’s one from UCL Special Collections’ Project Conservator, Laurent Cruveillier. His intent was to create a collection of cookbooks signed by their authors, and over 25 years he has put together a collection of over 500 books, from the 19th century to today. His collection is vast enough to include a sub-collection, of recipe booklets produced by American food and appliance companies.

Ultimately, you need to decide for yourself what it is about book collecting that you find fulfilling. Whether it’s the hunt for a title your collection is ‘missing’, the chance to connect with other people who share your interests, or simply owning books that you find special, book collecting should bring you joy.

Applying for the Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize

If you’ve got this far, you’re excited about book collecting, and you’re a student studying for a degree at a London-based university, you should absolutely consider entering the Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize. In brief:

- Applications are due by May 25, 2020

- The winner will receive £600, an allowance of £300 to purchase a book for UCL Special Collections (in collaboration with library staff), and the opportunity to give a talk on and/or display of their collection as part of the UCL Special Collections events programme.

- Applicants must fill in the Application Cover Sheet, appending an essay of not more than 500 words on their collection, a list of items in their collection, and a list of five items to add to their collection. More details on the requirements are listed in the cover sheet.

For more information on the Prize, including more information on how to enter and who qualifies for entry, please visit our website.

Further Reading:

With thanks to Laurent Cruveillier, Vicky Price and my parents for providing images of their own collections!

Close

Close