Galton Laboratory Records

By Sarah Pipkin, on 7 September 2023

Leah Johnston, Cataloguing Archivist (Records), shares details of the Galton Laboratory archive.

Content warning: This blog includes details of records and objects that relate to racist, ableist and classist beliefs. The ideas within this material do not reflect the current views of UCL.

The Galton Laboratory Records form a collection of archives recording parts of the laboratory’s history, from its creation in 1904, up to the late 1990s. Much of the material was donated to UCL Special Collections in 2011, with some smaller accessions added since then. Over the past year the collection has been fully catalogued and is now all available to view online.

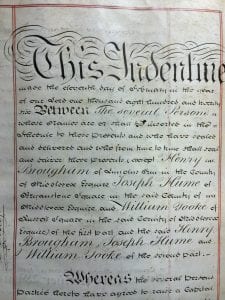

The origins of the Galton Laboratory at UCL can be traced back to 1904 when Francis Galton established the Eugenics Record Office in Gower Street, Bloomsbury. Although the laboratory was not officially part of the university at that time, a connection was formed with Galton endowing UCL with an annual £500 Fellowship of National Eugenics. In 1906 Professor Karl Pearson took over Directorship of the Eugenics Record Office, while still informally working alongside Galton. After Galton’s death in 1911, the residue of his estate was bequeathed to the university, under the condition that it was used to establish a Chair of Eugenics, whose role would be to direct research into ‘those causes under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations either physically or morally’.

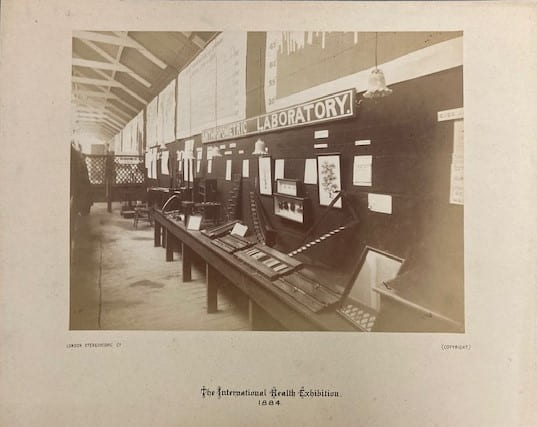

GALTON LABORATORY/4/1/8 – Photograph of the Anthropometric Laboratory, South Kensington, 1884.

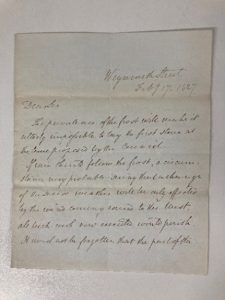

This early history of the laboratory is recorded in a series of administrative papers within the collection. Included is early correspondence between Galton, Pearson and P J Hartog (the then Academic Registrar), regarding their proposed scheme for a laboratory at the university, plus copies of Galton’s will and related planning for the establishment of a Chair of Eugenics. While these files include high level planning, other papers record more practical decisions, such as plans for the proposed new building. Below is an estimate for blinds to be supplied by James Shoolbred & Co. Ltd, including a small sample of green cloth.

GALTON LABORATORY/1/6/3 – Estimate for blinds from James Shoolbred and Co., including a sample of fabric, 1921.

Other series include papers accumulated by the laboratory, records of laboratory publications (such as the Annals of Eugenics, The Treasury of Human Inheritance and Eugenics Laboratory Memoirs), and research working papers.

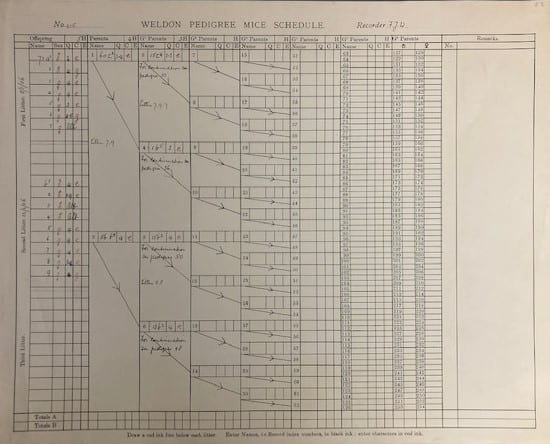

GALTON LABORATORY/2/3/3 – Weldon pedigree mice schedule, 1905-1906.

The remaining series consist of photographs, artwork, audio-visual material, and objects.

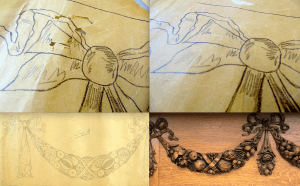

Artwork in the collection includes portraits of individuals connected either to Galton, or to the laboratory, alongside early watercolours of scientific specimens and samples. It appears from related annotations that they were either displayed in the laboratory or were used in their publications.

GALTON LABORATORY/4/2/6 – Watercolour illustrations of human eyes, 1915.

A series of photographs are similarly varied and were also used in publications, displayed in the laboratory, or kept as reference material. Included below is an image of Francis Galton seated on his porch, with his servant standing behind him and holding his pet Pekingese puppy.

GALTON LABORATORY/4/1/19 – Photograph of Francis Galton seated on his porch, with his servant Alfred Gifi, who is holding Galton’s Pekingese puppy, Wee Ling, c.1910.

This is contrasted against a more recent addition to the collection, which is one of three photographs showing women working in the laboratory in the early 1900s.

GALTON LABORATORY/4/1/17 – Women working in laboratory, early 20th century.

Alongside other UCL Library and Culture collections, the Galton Laboratory Records help to form a fuller record of the history of the laboratory and in turn, its legacy at UCL. If you would like to further explore the collection it can now be viewed on our online archives catalogue and by typing ‘Galton Laboratory Records’ into the search bar.

To make an appointment to view the records, or for any queries regarding the collection or the catalogue, please contact us at spec.coll@ucl.ac.uk.

Close

Close