December begins today, and with it we welcome you to Advent Definitions.

Each day this month, UCL Special Collections will be tweeting a festive word, together with a historical definition from our Rare English Dictionaries Collection.

Linked to the tweets will be regular blogposts highlighting aspects of the department’s work with UCL’s treasure of archives, rare books and records.

To get you into the spirit, we start with a traditional food around Michaelmas time: the poor goose:

‘Goose’, in: R 221 DICTIONARIES SHERIDAN 1800: Sheridan, Sheridan’s pronouncing and spelling dictionary (London, 1800)

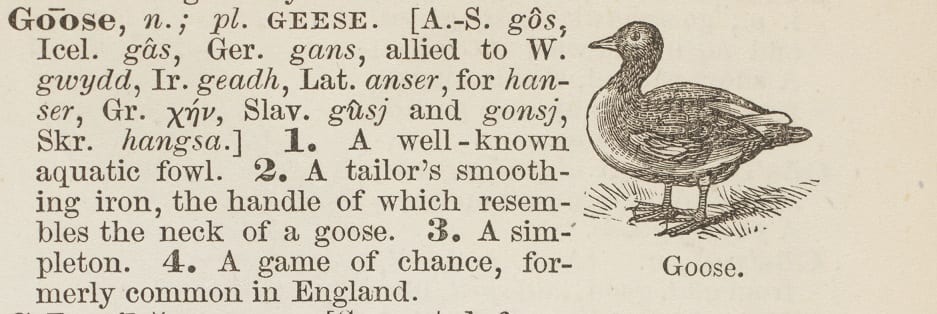

But while the goose might have suffered from a reputation for foolishness in 1800 and having its name used as a general term of abuse in 1869, there were other more respectful applications of the word:

‘Goose’, in: R 221 DICTIONARIES WEBSTER 1869: Webster, The people’s dictionary of the English language (London, [1869?])

And this is the kind of comparison for which the Rare English Dictionaries Collection was put together. When I started as Rare-Books Librarian at UCL, I was immediately interested in a small collection of English-language dictionaries gathered by my predecessor. I had worked in the past as a lexicographer for the

Oxford English Dictionary, and knew how helpful former dictionaries could be for researchers tackling the challenges of tracing English usage through time.

As my colleagues and I worked through various other collections of books at UCL, I came across more and more English dictionaries, mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries. Individually these books were not as significant as treasures we already kept in some of our more famous named collections, such as the Ogden Collection with its strength in language and communication. But gradually it became clear that, put together and used as a single resource, the less prized dictionaries could enable research that simply wouldn’t be possible using single editions of titles we already held, so the Rare English Dictionaries Collection was formed.

Most of the dictionaries in the Rare English Dictionaries Collection were published as ordinary household or student reference books, often intended to help with spelling or pronunciation. The title of Webster’s famous dictionary (which was to run into many editions over generations) indicates this: The people’s dictionary of the English language.

As a consequence, it is rare for copies in multiple editions to have survived, but in our collection, you can trace the appearance or disappearance of individual words across 50 or even 100 years of publication of dictionaries by lexicographers such as Bailey, Ash, Dyche or Entick. Former definitions would often simply be reprinted in later editions until the point was reached when the discrepancy between the old definition and current usage of the time became too stark. Being able to trace this in our collection gives C21st readers invaluable insight into how the language has changed.

Forming a usable collection takes a lot more than picking appealing books and putting them together. Our Conservation team, with the help of our invaluable volunteers from UCL and elsewhere alongside our placement students from Camberwell College of Arts, surveyed and cleaned the books. Our long-serving rare-books cataloguer Bill Lehm catalogued the collection before retiring after many years of wonderful work in UCL Library Services. I worked with academic staff to integrate the collection into UCL students’ curriculum, and we now hold regular classes with the collection for MA students studying English language.

For the Advent Definitions project, I would like to thank two student volunteers – undergraduate Odile Panette and MA student Christopher Fripp – who researched and read selected dictionaries to produce a shortlist of their favourite dictionary entries related to advent, Christmas or the holiday season. Finally Steve Wright, head of our Enquiries Team, photographed the entries you will see in our tweets, and Helen Biggs has managed the process of bringing you your daily word.

We hope you enjoy your daily advent definitions. To find out more about the dictionaries available, browse our catalogue by the shelfmark R 221 DICTIONARIES. And if you need convincing of the extraordinary power of keeping such material together in a classified collection, or just want a good library drama for the holidays (admittedly more 20th-century than, I hope, our 21st-century approach), try Stephen Poliakoff’s 3-part BBC drama, Shooting the past. (Viewers from UCL or other subscribing institutions can view this on Box Of Broadcasts.

For more daily advent-inspired definitions from our Rare English Dictionaries collection, follow @UCLSpecColl on Twitter.

Contributed by Tabitha Tuckett, Rare Books Librarian

Close

Close

The stories include ‘Battle of Frogs and Mice’, a short animal epic ascribed to Homer in the ancient world and ‘The Three Caskets’ which was used in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. The book also contains a couple of firsts: the first appearance of a Norwegian folk tale ‘The History of Asim and Asgard’ and the first publication of Scott’s poem ‘The Bonnets of Bonny Dundee’ (Hahn, 2015, p. 127). In addition, there are writings by the prolific author of adult and children’s stories Maria Edgeworth (1768 – 1849) who also wrote the well-known education treatise

The stories include ‘Battle of Frogs and Mice’, a short animal epic ascribed to Homer in the ancient world and ‘The Three Caskets’ which was used in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. The book also contains a couple of firsts: the first appearance of a Norwegian folk tale ‘The History of Asim and Asgard’ and the first publication of Scott’s poem ‘The Bonnets of Bonny Dundee’ (Hahn, 2015, p. 127). In addition, there are writings by the prolific author of adult and children’s stories Maria Edgeworth (1768 – 1849) who also wrote the well-known education treatise