This guest blog post was written by Isobel Goodman, who spent six months volunteering at UCL Special Collections as part of the Liberating the Collections project.

Tasked with researching pre-1750 women writers, as part of UCL’s Liberating the Collections project, I was struck by the varied ways in which women engaged with print culture in this period. Unsurprisingly, recognised names such as Margaret Cavendish, Mary Wortley Montagu and Aphra Behn occur frequently in the catalogues, but the research also revealed several other women writers whose non-aristocratic status and lesser-known writings provided a fascinating insight into the processes at work.

*****

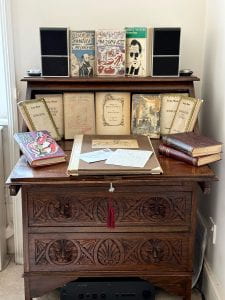

Mrs James’s Vindication of the Church of England in an answer to a pamphlet entituled A New test of the Church of England’s loyalty. (London, 1687) [UCL Special Collections Huguenot Library JB 17 HAL]

The political writings of author-printer

Elinor James (1644-1719) were regularly published even before she inherited her husband’s printing business in 1710. Renowned for her petitions to the king and parliament, James’ work benefitted from ready access to a printing press: not only could her concerns be published promptly in response to new debates (hence avoiding any appearance of pre-meditated attack on the petitionee), but also in large quantities for maximum impact. Extant documents indicate that she penned at least 90 pamphlets and broadsides during her career, although the ephemeral nature of these items could disguise a much greater number. UCL holds

a copy of

Mrs James’ Vindication of the Church of England (1687), in which she defends James II’s ‘Declaration of Indulgence’ against criticism in another pamphlet published anonymously weeks earlier. Robustly countering the anti-Catholic stance of the earlier publication, James concludes “GOD Save the KING”!

Portrait of Elinor James, c.1700 ©Wikimedia Commons

The fast, cheap, ephemeral nature of pamphlet production suggests that James sought neither literary renown nor fortune from her writing. However, the conspicuous inclusion of her name in her publications, often in the title itself, demands recognition as both author and printer. Indeed, a portrait she gifted to Sion College in 1711, notably depicts James holding a lavishly bound book whilst a copy of her Vindication of the Church of England rests nearby.

*****

Poems upon several occasions. By the late Mrs Leapor, of Brackley in Northamptonshire. The second and last volume. (London, 1751) [UCL Special Collections Strong Room E 221 L2]

In the absence of owning a press, less-wealthy eighteenth century authors could fund the third-party publication of their writing through subscription i.e. half of the book price paid in advance by readers and the other half on receipt, in return for their names being listed in the publication itself. Kitchen maid,

Mary Leapor (1722-46), was an unlikely candidate for a published poet, yet she successfully funded printing in this way – no doubt aided by subscribers’ curiosity of her situation. Rector’s daughter, Bridget Freemantle, and Leapor’s employers and their relations (the Jennens and Blencowes) also provided useful connections.

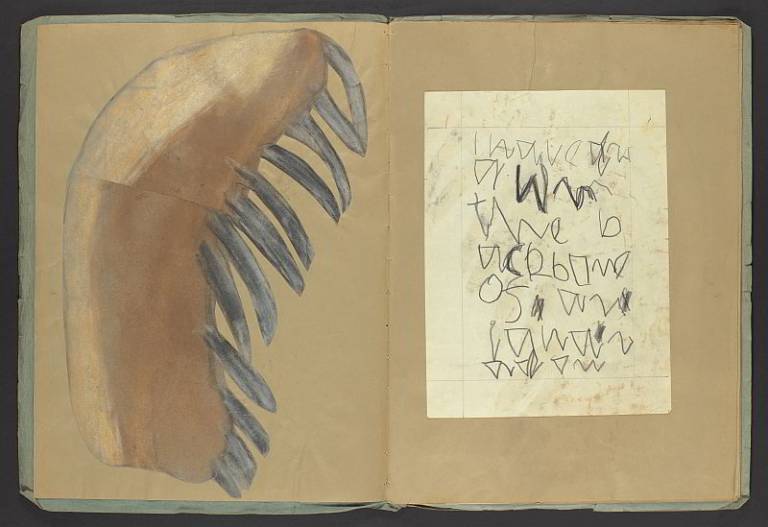

Rear flyleaf of Poems upon several occasions. By the late Mrs Leapor, of Brackley in Northamptonshire. The second and last volume. (London, 1751) [UCL Special Collections Strong Room E 221 L2]

Following Leapor’s premature death, two years before her book appeared in print to positive reviews, novelist Samuel Richardson published a posthumous second volume of Leapor’s manuscripts (1751), of which UCL holds

a copy. While less successful in attracting subscribers, the text’s woodcuts still suggest a reasonable budget. Leapor was certainly well-known during this period: an anthology ‘by eminent ladies’, published in 1755, devoted more pages to her than any other writer. Indeed, UCL’s text previously belonged to Jeremy Bentham and includes his annotations of ‘Mrs Grey’s memories of Mary Leapor’, indicating a prestigious readership of both sexes. Bentham reports that Mrs Grey introduced Leapor to Bridget Freemantle, who subsequently provided her “with pens, ink & paper & a bureau, book case & likewise books, before which she had scarcely an opportunity of coming at any books, or the means of procuring them”.

*****

In contrast, the corpus of poems, prose, petitions, biography and translations penned by Lucy Hutchinson (1620-81) remained deliberately unpublished during her lifetime. She is perhaps best known for her Memoirs of her husband, John Hutchinson – a signatory of Charles I’s death warrant who died in prison following the Restoration – which she compiled for their children between 1665 and 1671.

Lucy Hutchinson by Samuel Freeman, stipple engraving, circa 1825-1850

NPG D19953 ©National Portrait Gallery

The Memoirs’ posthumous publication in 1806, by Hutchinson’s great-great-grandson, raises questions about the control authors ultimately had over their work. The private account was intended as “a naked undrest narrative, speaking the simple truth of him”, confirmed by careful, personal revisions of the original manuscript. Yet the heavily edited (although well-received) first publication was swiftly followed by two further editions before 1810. UCL special collections hold five four copies, ranging in date from 1808 to 1904. The original editor promoted the text to female readers as having “all the interest of a novel”, and the book’s moralistic account of the civil war impacted both historiography and popular opinion, despite no evident intent by Hutchinson to do either.

*****

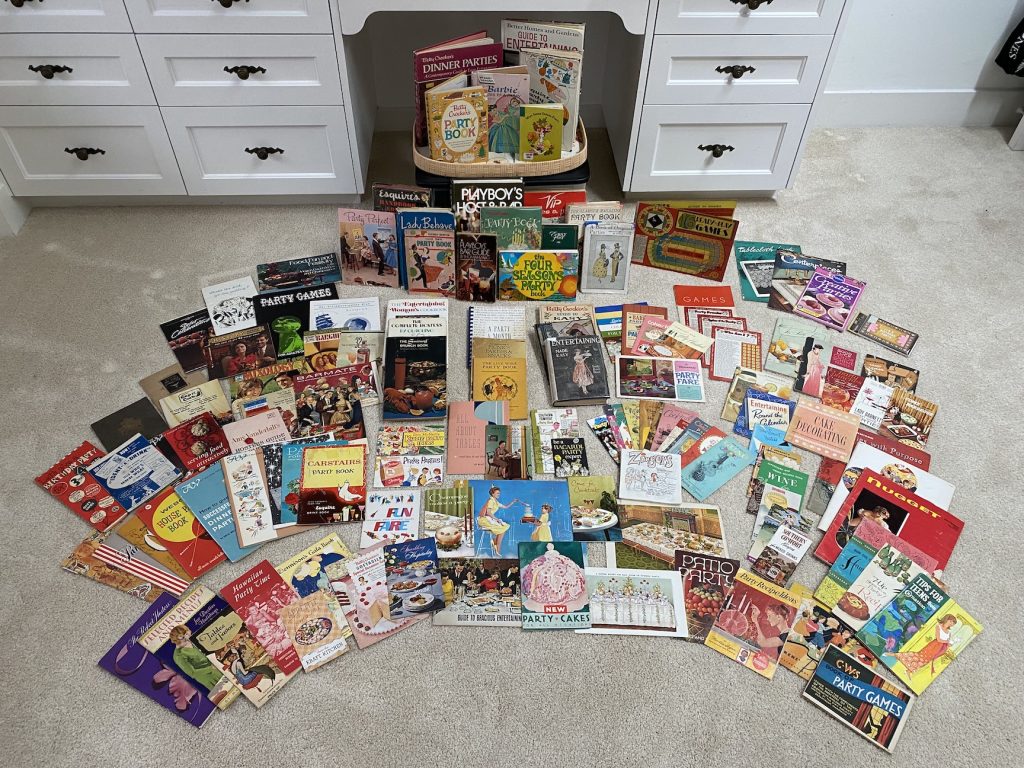

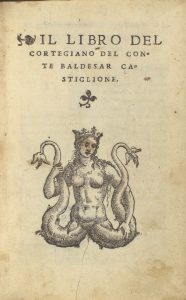

An apology for the conduct of Mrs Teresia Constantia Phillips (London, 1748) [UCL Special Collections OGDEN MUI (1)/1]

The

scandalous memoirs published in 1748-9 by

Teresia Constantia Phillips (1709-65) were perhaps originally penned more for blackmailing former lovers than for book sales! In a self-promoting sales tactic, the imprint claims, “Such extraordinary care has been taken to intimidate the Booksellers, in order to stifle this Work, that Mrs. Phillips is obliged to publish it herself, and only at her House in Craig’s Court, Charing Cross; and to prevent Imposition, each book will be signed with her own hand”. Yet, in reality, the removal of pre-publication censorship during the 18

th century had freed publication of such material in Britain. Trade publishers, such as Mary Cooper, who would assign their own name to an imprint and sell publications anonymously on behalf of the publisher and copyright holder, further enabled publishers to print controversial works without risk to their reputation.

Portrait of Teresia Constantia Philips, in An apology for the conduct of Mrs Teresia Constantia Phillips (London, 1748) [UCL Special Collections OGDEN MUI (1)/1]

*****

Whether for money, renown, or politics, the women represented in UCL’s special collections employed authorship for their own purpose – albeit with varying control over the resulting publications. Literacy was expanding during the 17th and 18th centuries, as was the print market following the lifting of restrictions on printer numbers in 1695. Combined with women’s evident interest in matters beyond the household (despite being unable to fully participate or vote in them) the processes were in place for them to reach a wider audience than ever before, through the medium of print.

By Isobel Goodman

Bibliography

Primary sources

Hutchinson, Lucy. Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson. London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Roes and Orme by T. Bensley, 1810.

James, Elinor. Mrs James’s Vindication of the Church of England, in an Answer to a Pamphlet entituled, A New Test of the Church of England’s Loyalty. London: Printed for me, Elinor James, 1687.

Leapor, Mary. Poems upon Several Occasions. The second and last volume. London: Printed and sold by J. Roberts, 1751.

Muilman, Teresia Constantia. An Apology for the Conduct of Mrs Teresia Constantia Phillips. London: Printed for the Author, and sold at her house in Craig’s-Court, Charing Cross, 1748-1749.

Secondary sources

Brown, Susan, Clements, Patricia, Grundy, Isobel. “Elinor James: Writing,” Orlando: Women’s Writing in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the Present, last accessed 03/08/2021. http://orlando.cambridge.org.ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/protected/svPeople?formname=r&people_tab=2&person_id=jameel&crumbtrail=on&dt_end_cal=AD&dt_end_day=27&dt_end_month=06&dt_end_year=2021&dt_start_cal=BC&dt_start_year=0612&dts_historical=0612–+BC%3A2021-07-12&dts_lives=0612–+BC%3A2021-07-12&dts_monarchs=0612–+BC%3A2021-07-12&heading=h&name_entry=Leapor%2C+Mary&subform=1&submit_type=J

Greene, Richard. Mary Leapor: A Study in Eighteenth-Century Women’s Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Hutchinson, Lucy. Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Mayer, Robert. “Lucy Hutchinson: A Life of Writing,” The Seventeenth Century, Vol. 22(2) (2007): 313.

McDowell, Paula McDowell. “Introductory note” in Elinor James. The Early Modern Englishwoman: A Facsimile Library of Essential Works, Printed Writings, 1641-1700: Series II, Part Three, Volume 11. Ed. Paula McDowell. London: Routledge, 2017.

Plaskitt, Emma. “Phillips [married name Muilman], Teresia Constantia (1709-1765],” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-22170

Treadwell, Michael. “London Trade Publishers 1675-1750.” The Library Series 6, Vol. IV, No. 2 (1982)” 99-134.

Close

Close