Our first UCL Special Collections Visiting Fellow, Adrian Chapman (Florida State University London Centre), writes below about the research that arose from his fellowship with us during the summer of 2019, working on our Small Press Collections.

Consider the following elements. R. D. Laing, a radical Scottish psychiatrist who lived from 1927 to 1989. A Neolithic stone circle. A flying saucer. And The Rolling Stones.

What could they possibly have in common? There doesn’t seem much, or indeed anything at all, that links them.

But they’re all brought together on a front cover of International Times, a London-based underground press publication. The 59th issue of IT (as the paper was known), is from July 4th, 1969.

Let’s try to make sense of these apparently unrelated elements. Here they are on the cover:

Cover, International Times no 59, 4-17 July 1969 (image courtesy of UCL Special Collections)

The photo of hippies and gowned pagans at Stonehenge referred readers back to the Summer Solstice, a couple of weeks before the issue’s publication. The image reveals an abiding underground interest in the ancient and esoteric. In IT this preoccupation is represented by the writing of John Michel (someone who in his later years wrote a column for The Oldie in which he raged against decimalized currency and other supposed horrors of the contemporary world).

R. D. Laing’s name is on the lower level of the UFO but is difficult to read. A close-up of the saucer will be easier on your eyes:

Cover detail, International Times no 59, 4-17 July 1969 (image courtesy of UCL Special Collections)

You can also read the following words, looping out of the saucer to the right of the craft: ‘Coming to the park? Saturday 5th July. See page 23. See you there.’ No further details are given (or required). IT could safely assume its readership needed nothing more. The reference is to a free concert (in Hyde Park) headlined by The Rolling Stones. At the gig, Mick Jagger read an extract of Shelley’s poem ‘Adonais’ (his elegy for Keats) in remembrance of the recently deceased Stones’ founding member Brian Jones. Inside IT 59 is an interview with Jagger. Music, of course, was central to the underground scene.

I came across this issue of IT when poring over UCL’s excellent collection of underground publications from the 1960s and 1970s. As the college’s 2019 Special Collections Research Fellow, I began work in the Special Collections room by searching for evidence of R. D. Laing’s place in the underground or ‘counter-culture.’ That meant carefully sorting through box after box of old newspapers and magazines: painstaking work. When I delicately removed a yellowing and flaky newspaper and saw a flying saucer with Laing’s name on it, I was intrigued.

You may not be familiar with Laing. In the 1960s and 70s, he was a public intellectual and celebrity, the most well-known therapist in the world: the Mick Jagger of psychiatry. His books were on the shelves of students, hippies and radicals on both sides of the Atlantic. Born in Glasgow, where he studied Medicine, he moved to London in 1956 to train in psychoanalysis. He went on to become a widely selling Penguin author. His The Divided Self (1960) impressed Jean-Paul Sartre so much that the French philosopher remarked that existentialism had found its Freud. Laing’s later books, The Politics of Experience (1967) and Knots (1970), sold particularly well.

His work critiqued psychiatry for treating patients, especially schizophrenics, as objects or bundles of symptoms rather than people in need of companionship. He called for greater acceptance of one’s own and others’ eccentricities. Society had become dull and unadventurous, he believed, requiring increasing conformity. He promoted experimental lifestyles, alternative education and consciousness expansion.

These views placed him at the heart of the counter-culture, which rejected much of what passed for convention and sought (in the words of Jim Morrison) to ‘Break on through to the other side.’ Laing’s celebrity extended across Europe and over to the United States. In Autumn 1972, he toured the US college lecture circuit and addressed packed-out auditoriums on a gruelling coast-to-coast tour.

As I delved deeper into UCL’s underground press holdings, I found more about Laing in the 1960s and 70s papers and magazines. There were features, interviews and advertisements for books and events. Laing and his colleagues can be found quite frequently in the main UK underground publications: IT, Oz, Friends (later Frendz) and Ink.

These publications reflected, and helped form, a youth culture opposed to mainstream values. I found a remarkably wide range of topics—drugs, police corruption, housing, sex and sexuality, racism, ecology, food and music. Politics and international affairs, too. Plus material on flying saucers, the occult, ancient archaeology and mental health. It’s difficult to conceive of a periodical today having such a surprisingly broad range. Laing was part of the curious mish-mash of ideas, groups and interests that constituted the UK underground in the 1960s and at the start of the 70s.

Long before Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, underground publications brought people together and spread news beyond the mainstream. International Times was the UK underground’s first, and longest lasting, regular publication, beginning in 1966 and running up until 1974 (and on and off since then all the way up to the present). To people working on the paper, it was known as IT, and the IT logo was enough on issue 59 to identify the publication for readers. Along with the logo on the cover, there’s the IT girl (as she was known). She was intended as a playful reference to the paper’s title. Who better to use as an emblem than Clara Bow, the silent movie actress and original ‘It Girl’ who starred in a 1927 movie entitled It? Either through accident or design, though, the woman who ended up on the cover was not Bow but Theda Bara, another silent movie queen, renowned for her vampish roles.

In 1966, on the paper’s very first front cover, three questions appeared beneath the IT logo and the IT girl: ‘Who us? What us? Why us?’ The questions opened a mood of self-examination, not only about the nature of the paper but also about the nature of the UK underground, that would preoccupy the paper throughout its often-fractious history.

But the magazine’s 59th issue gave an answer to quite what IT was. If you look again at the image of the flying saucer, you’ll see a cigar-shaped form out of which come zig-zags looking like radio signals. What, we might ask, is the saucer broadcasting? Two words emerge: ‘INSANITY TIMES.’ We can also find ‘Midsummer Madness Issue’ written on the side of the saucer’s upper level. The issue is principally concerned with mental illness.

What could that possibly have to do with a UFO? And why would underground magazines be interested at all in flying saucers? In the age of Apollo and the USA-USSR space race, underground publications cared little for the superpowers’ rocket missions. But there was a sustained preoccupation—albeit one not shared by everyone identifying with the underground—with flying saucers.

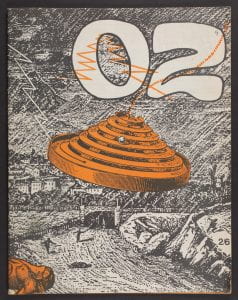

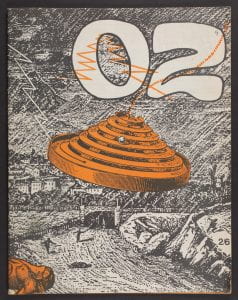

At Oz magazine, alongside IT the leading organ of the London underground, interest in UFOs came from the Australian psychedelic artist, Martin Sharp. He edited Oz 9 (February 1968) and put a saucer on the cover:

Cover, Oz no 9, February 1968 (©Martin Sharp Trust)

In the magazine, Sharp also included a six-page UFO supplement. One page before it comes a full-page, very psychedelic Sharp illustration. And there is a Laing connection here. The illustration is based on a sentence of Laing’s (from his prose poem The Bird of Paradise): ‘If I could turn you on, if I could drive you out of your wretched mind, if I could tell you I would let you know.’

Oz no 9, p.13 February 1968 (©Martin Sharp Trust)

This artwork takes the reader deep into inner space. Writing in his 1967 text, The Politics of Experience, a book that became a campus bestseller, Laing maintained that voyaging into inner space, even to the extent of psychosis (which, he believed, could be a natural healing process) could for some people be a route out of mental ill-being and into lives of greater freedom and authenticity.

For sure, there were people in the underground who believed in aliens (and government cover ups). But we can also read ‘underground UFOs’ as metaphors for the exploration of inner space. Hallucinogenic drugs provided a way of voyaging through this terrain. But so too did Laing’s idea of a ‘mad voyage’, an exploration of one’s self to the point of madness, ending (hopefully) in a ‘re-birth.’ It makes sense, then, that Laing’s name is on the IT 59 saucer.

But although the issue gives us Laing ‘on the same page’ or the same ‘wavelength’ as flying saucers, Stonehenge and The Rolling Stones, we should not assume that Laing himself shared such fascinations. While he was a source of inspiration to rock musicians (as I’ve explored in an article for the Wellcome Collection), as a classically trained pianist, he probably preferred Bach to The Stones. I have no idea what he thought of stone circles, but to my knowledge he had no interest whatsoever in UFOs.

Inside IT 59 there is an interview with him, and seven photographs of the doctor along with one of him and his interviewer, Felix Scorpio. Deemed worthy of eight photos, we can assume that Laing was someone IT readers very much wanted to see. I found myself most curious about the photo introducing the interview.

Elegant in a white shirt and black tie, and with his hair carefully combed, Laing looks back over his left shoulder at Scorpio, long-haired and wearing a casual jacket. Laing has two fingers of one hand on a sheet of paper while he writes with his other hand. You can see that he is very much the ‘straight’ doctor in his consulting room with a patient.

Photo of RD Laing, International Times no 59, July 4-19 1969 (image courtesy of UCL Special Collections)

We can assume that the photo was ‘staged.’ But it’s interesting to think of what the image ‘says.’ Let’s imagine what Laing might be writing, then. While he avoided diagnostic categories and tended not to write prescriptions, the picture makes me think that here the doctor is scribbling diagnostic notes or perhaps scratching out a prescription. In the context of IT and its preoccupation with its own nature, plus its reflexive concern with the underground’s character, perhaps the good doctor is making notes to help him diagnose the underground. Or perhaps he’s writing a prescription to improve its health.

The interview itself is one that could never have appeared in a mainstream publication. It contains too much swearing, for one thing. And Scorpio moves between the stance of a conventional interviewer and the position of a former patient reflecting upon his breakdown and hospitalisation. He smoked pot in the hospital toilets and this greatly improved his condition, he tells Laing, who avers that cannabis and that psychedelics have their place in mental illness treatment.

‘Insanity Times’ contains more about mental illness. The longest article is about Georg Groddeck (1896-1934), a Swiss-German doctor who wrote The Book of the It and strongly influenced Sigmund Freud. Groddeck argued that a mysterious force, ‘It’, forges our mental and physical condition. Given IT’s self-reflexive stance, it was very much in the paper’s character to devote significant space to an examination of someone who wrote a text entitled The Book of the It. The long article makes use of quotations from Laing (and others including Nietzsche, Kahlil Gibran and Jimi Hendrix) to help IT readers make sense of Groddeck’s work.

Two more pieces in the issue show the influence of Laing. An article about a new mutual support group, People Not Psychiatry, presents mentally disturbed people in a very Laingian fashion as members of the resistance against conformity. There’s also a first-person account of breakdown by someone writing under the name of ‘Alan.’ An introduction to the article tells us that although he’s now able to ‘cope’, Alan had not been able to fully carry out his ‘trip.’ Madness as a trip: very countercultural and very Laingian.

That Laing was the counterculture’s favourite psychiatrist is not news. But my close examination of the underground press has allowed me to investigate key historical sources and start addressing Laing’s place in the underground in detail. Sorting through dusty and fragile copies of IT in the UCL Special Collections room, how fortunate I was to come across number 59 from June 1969. The issue provides strong graphic and verbal evidence of how Laing was taken up by the UK underground.

This article comes out of a research fellowship at UCL Special Collections. Thanks to the staff at UCL Special Collections for their aid in finding materials in the Small Press collection.

Thanks also to the Martin Sharp Trust for permission to use images from Oz magazine.

If you would like to discuss the article, do get in touch. E-mail: anchapman@fsu.edu; Twitter: @dradrianchapman

Close

Close

Politics and social policy, especially 19th and 20th century reform movements

Politics and social policy, especially 19th and 20th century reform movements