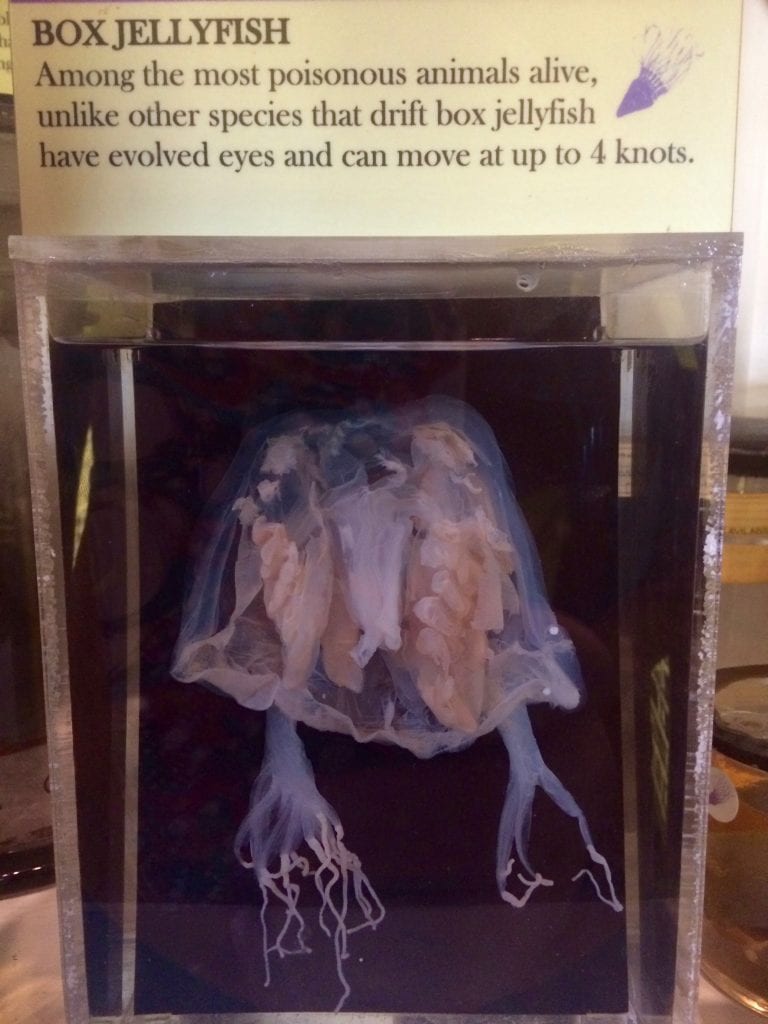

This week it’s time for another of my favourite objects from the UCL museums, today from the collections of the Grant Museum of Zoology. Displayed in a case near the front of the museum is a collection of extraordinary objects. At first glance, these objects appear somewhat otherworldly; their lightly transparent and almost twinkling surfaces captured my attention from my very first visit. They are, of course, the Grant Museum’s collection of glass models of invertebrates, a collection that includes jellyfish, sea anemones, gastropods, and sea cucumbers, produced at the end of the nineteenth century by the Blaschkas, a renowned family of Czech jewellers.

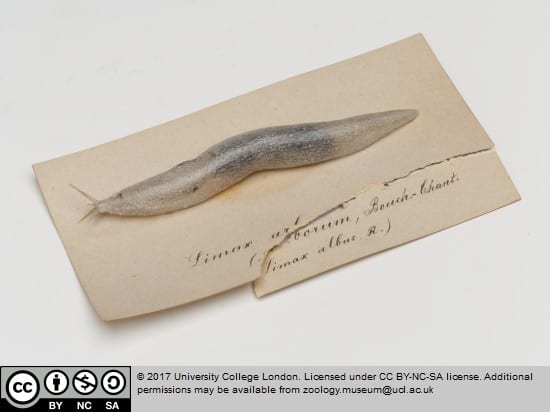

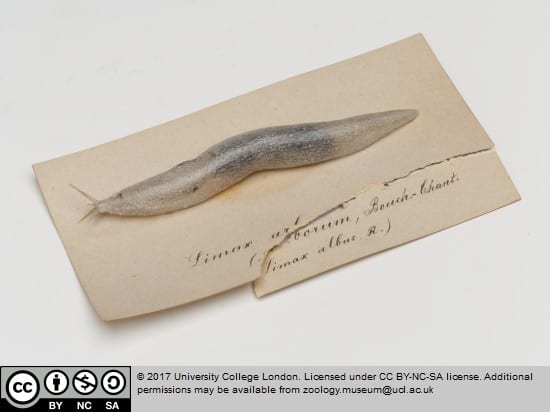

Limax arborum (tree slug). Blaschka glass model of a white slug, (P202). Image credit: Grant Museum.

Actinia equina (beadlet anemone). Blaschka model of a beadlet anemone. Red/orange body with white beadlets. The tentacles are transparent. On a black wooden base, under a glass dome, (C373). Image credit: Grant Museum.

The Blaschka family

The models in the museum’s collection were produced by Leopold and his son Rudolph Blaschka in the late 1800s, and may have been ordered by E. Ray Lankester during his time at UCL as professor of zoology.[i] Leopold Blaschka was born in 1822 in Northern Bohemia (today part of Czechia), in Aicha, a village known for its glasswork and decorative crafts.[ii] The Blaschka family specialised in producing jewellery using a range of materials, including glass, metal, and semi-precious stones. During his career, Leopold developed an interest in natural history, and began producing and selling models of invertebrates in the mid-1860s. The models were created using glass, wire, glue and paint, and occasionally incorporated parts of once-living creatures, including snail shells (see below).[iii] Today, Blaschka invertebrate models can be found in museums all over the world. The Harvard Museum of Natural History also holds a collection of glass flowers created by the Blaschkas, commissioned by the university in 1890.[iv]

Arianta arbustorum (copse snail). Blaschka glass model, (P196). Image credit: Grant Museum.

Why make specimens out of glass?

Passing the collection of models for the first time, a visitor to the Grant Museum could be forgiven for mistaking these models for specimens that were once alive. In light of the museum’s other displays, which feature real animals preserved using a variety of methods, one might wonder why artificial specimens, such as the Blaschka models, should be on display in a museum of natural history. While some creatures, such as mammals, birds, and fish, are easily preserved using methods of taxidermy, flowers and the softer bodies of invertebrates pose specific challenges in terms of their preservation. Putting these specimens into alcohol causes them to lose their shape and colour.[v] By creating models out of glass and other materials, it is possible to depict the vibrant colours and forms of the original specimens, allowing these creatures to be preserved and studied.

Art, Science, and ‘Jokes of Nature’

Former student engager Niall Sreenan has mused on the nature of the Blaschka models as artificial creations that occupy an ambiguous realm between nature and art.[vi] As a historian of science, I am fascinated by this interplay, particularly as it relates to the practice of natural history and the display of specimens. The relationship between art, nature, and science held great significance to the practice of natural history in sixteenth and seventeenth-century Europe. As the historian Paula Findlen has noted, collectors of natural specimens in the Early Modern period were fascinated by the idea that Nature, as a creative force who produced all the objects and creatures in the world, sported or played in her work by producing ‘jokes of nature’.[vii] Such ‘jokes of nature’ incorporated instances where natural objects appeared to ‘mimic’ human artifice, as seen in unusual fossils, geometric crystals, or in stones which appeared to have pictures implanted within them.[viii] ‘Jokes of nature’ were connected to science through the idea that man might match nature using art. Artificial creations and human imitations of natural forms were thought to mimic these jokes in a way that was central to natural philosophers’ understanding of the world.[ix]

Though produced over a century later, the Blaschka glass models call to mind this ambiguous division between human artifice and natural object. As models of difficult-to-preserve specimens, they allow visitors to understand what these creatures look like. On the other hand, they draw attention to human ingenuity and skill in the way they artfully capture the look of organic specimens.

Sea cucumber (female). Blaschka glass model in a cylindrical specimen jar, (S73). Image credit: Grant Museum.

The end of a craft

In 1895, Leopold Blaschka died. When his son retired in 1938 with no apprentices left at the firm, the Blaschka family business closed.[x] The skills used to produce the models died with the Blaschka family, and their work has not been repeated since.[xi] The models in the Grant Museum stand as a remarkable testament to unique craftsmanship and skills now lost.

Though models are no longer produced using the techniques once used by the Blaschka family, the relationship between art and natural history continues to fascinate contemporary artists. Grant Museum Manager Jack Ashby has recently written about the ways in which artists explore and reference the methods of natural history, and the treatment of both living and preserved animal specimens on display.[xii] Exploring the intersection of natural history and art, whether in the creation of model specimens or in the interrogation of the practices of natural history, can prompt us to question the ways in which natural and man-made objects are encountered in museums, and the way we understand an object’s (and our own) relationship with the natural world.

References

[i] ‘Blaschka Glass Model Invertebrates’, UCL Grant Museum, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/culture/grant-museum-zoology/blaschka-glass-models-invertebrates [Accessed 23 April 2018].

[ii] ‘Blaschka Models’, National Museums Scotland, https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/natural-world/blaschka-models/ [Accessed 23 April 2018].

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] ‘Blaschka Models’, National Museums Scotland, https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/natural-world/blaschka-models/ [Accessed 23 April 2018].

[vi] Niall Sreenan, ‘”Strange Creatures” – Reflections – Part One’, 25 June 2015, https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/researchers-in-museums/2015/06/25/strange-creatures-reflections-part-one/ [Accessed 23 April 2018].

[vii] Paula Findlen, “Jokes of Nature and Jokes of Knowledge: The Playfulness of Scientific Discourse in Early Modern Europe,” Renaissance Quarterly 43, no. 2 (1990): 292-96.

[viii] Ibid., 297-98.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] ‘Blaschka Models’, National Museums Scotland, https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/natural-world/blaschka-models/ [Accessed 23 April 2018].

[xi] ‘Blaschka Glass Model Invertebrates’, UCL Grant Museum, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/culture/grant-museum-zoology/blaschka-glass-models-invertebrates [Accessed 23 April 2018].

[xii] Jack Ashby, ‘When Art Recreates the Workings of Natural History it can Stimulate Curiosity and Emotion’, 19 April 2018, https://natsca.blog/2018/04/19/when-art-recreates-the-workings-of-natural-history-it-can-stimulate-curiosity-and-emotion/ [Accessed 23 April 2018].

Close

Close