Myths in the Museum: The Iron-Eater and the Ostrich Egg

By Jen Datiles, on 4 July 2019

This is the fourth segment in the Myths in the Museum series; you can go back and read about the horseshoe crab, the dugong and mermaid, and the narwhal and unicorn.

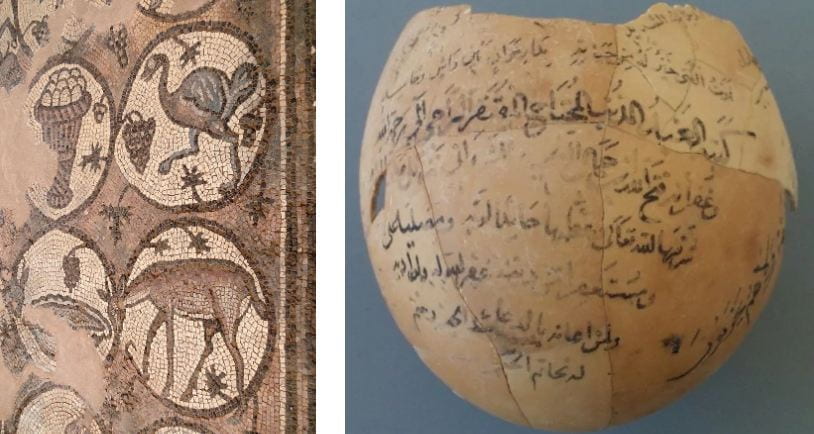

The now-extinct Arabian ostrich, depicted in The Book of Animals, 1335. [Source: The Book of Animals of al-Jahiz, Syria]

The UCL Grant Museum of Zoology is currently undergoing a significant restructuring of its displays. The Grant Museum is the last of London’s university natural history museums and has amassed a fascinating collection — but only a fraction is on display. From a set of warthog and domesticated pig skulls now placed over the entranceway as part of the expanded comparative anatomy section, to a lost set of dodo bones found in a drawer in 2011, to the world’s rarest skeleton, the extinct quagga (think zebra with fewer stripes), the museum’s collection is vast. In the newly reorganised avian section, some exceptionally large bird eggs are neatly lined up like a mini hall of fame. And the largest (non-extinct) egg of all, of course, belongs to that famous 9-foot-tall marvel with legs strong enough to kill a lion in one blow, the OG kickstarter, the Ostrich.

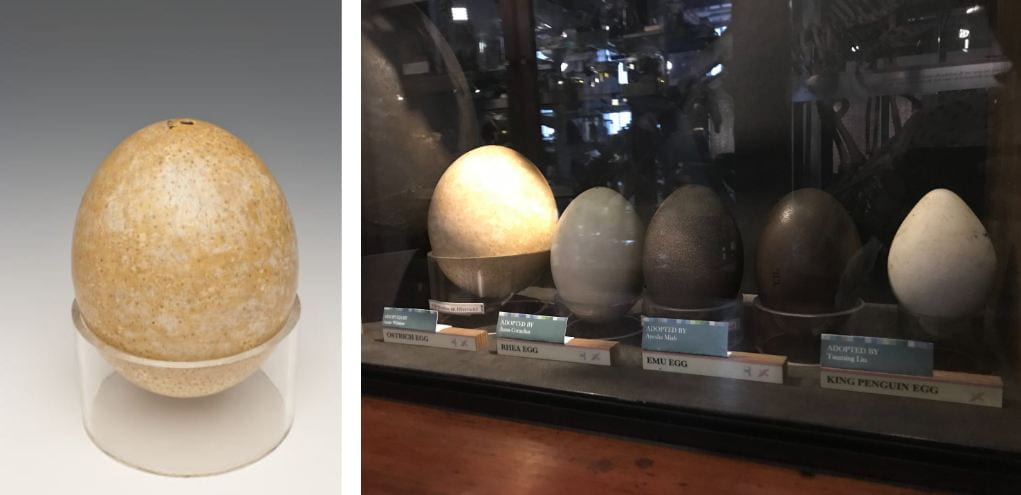

At the Grant Museum of Zoology, you can compare the pale-coloured ostrich egg with other large birds’ eggs. The photo on the left shows the individual ostrich egg; the photo on the right shows the museum’s display, with the now-extinct elephant egg dwarfing the rest, and the ostrich egg next to it. [Left: UCL Grant Museum, Y134; Right: image by Jen Datiles]

Left: A mosaic floor in the Byzantine Church of Petra, Jordan [Photo: Bernard Gagnon]; Right: A 15th-century ostrich egg with Arabic writing, describing the soul’s journey from death to life [Copyright University of Leeds. Source: Nature, 2002]

Ostrich eggs remained both spiritually and practically significant in the Greek and Roman worlds, where they were offered to deities and hung in temples as decorations or used as lamps. This association of ostrich eggs with sacred spaces carried over into Muslim and Christian practices. The ostrich, according to popular belief in the 2ndcentury BCE, the ostrich had the ability to make its eggs hatch by staring at them intensely rather than brooding, a trait that added to their significance as early Christian symbols of not only new life and rebirth, but also of single-mindedness, concentration, and determination. Pliny the Elder wrote on the ostrich’s mythical ability to eat iron and glass, which earned the bird a reputation as an iron-eater, and symbolized strength through resistance and hardship. In medieval and early modern Europe, the ostrich egg also came to symbolize the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary.

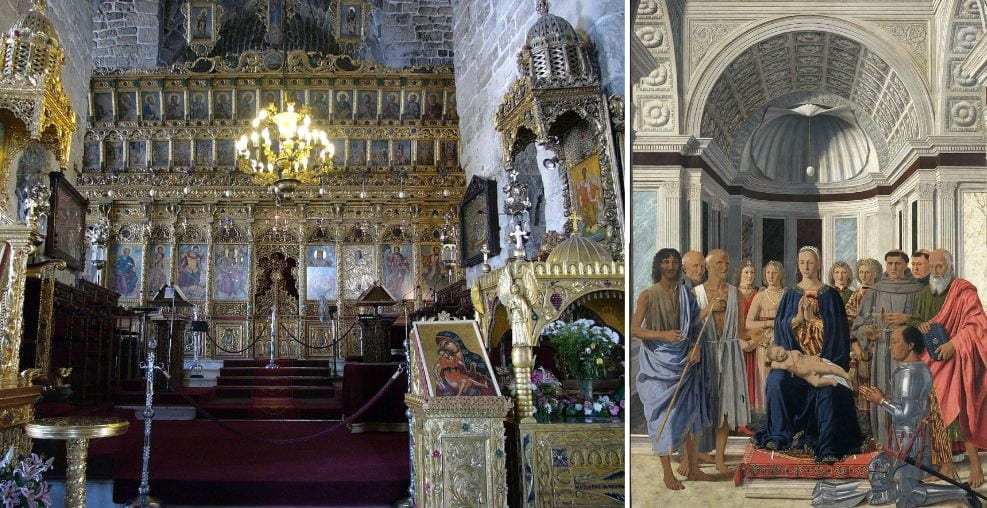

Left: Ostrich eggs add both symbolism and splendor to the interior of the Lazarus Church in Cyprus. [Photo: Hannes Grobe/BHV]; Right: Piero della Francesca’s Brera Madona c. 1472, an altarpiece known for its pendant egg detail. [Source: Wiki Commons]

In the secular luxury trade of the 16-17th centuries, ostrich eggs became a subject of particular fascination for metalsmiths. Last week I oohed and ahhed my way through the famously fantastic Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany. Amongst all the royal treasures of gems, ivory, gold, and crystal, a wall of the Grünes Gewölb (Historic Green Vault) was devoted to some seriously decorated ostrich eggs. These specimens had been fashioned with gilt-silver into figurines, goblets, and drinking vessels that once adorned the feast tables and halls of Saxon princes. Talk about egg-cellent conversation pieces!

Left: Three ostriches, fashioned from eggs mounted in gilt-silver. Elias Geyer, c. 1595, in the Grünes Gewölbe, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden [Source: SKDresden Online Collection]; Right: An ostrich egg standing cup, c. 1570, from the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Note the horseshoe in the ostrich’s beak — a reference to its mythical ability to eat iron [Source: Wiki Commons].

Ostrich eggs may also have use in modern medical research. Like all birds, ostriches pass on bacteria- and virus-fighting antibodies to their offspring through their yolk. Considering one ostrich egg contains as much yolk as about 24 chicken eggs, and one ostrich female can lay 50-100 eggs per year, a team of Japanese researchers have identified ostrich eggs as a promising source for developing drugs. Last October, they announced the commercial development of an ostrich antibody for dengue fever. The research is open to speculation, and still years away from clinical trials and regulatory approval, but our fascination large eggs continues!

Further reading:

Green, N. (2006) Ostrich Eggs and Peacock Feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam, Al-Masāq,18:1, 27-78, DOI: 10.1080/09503110500222328

Close

Close