Colours of Ancient Egypt – Introduction

By Anna Pokorska, on 18 August 2018

When viewing exhibitions of objects from ancient Egypt (or any ancient civilisation for that matter) we are used to seeing the beige and grey appearance of bare stone. Indeed, we have come to appreciate the simplicity and purity of ancient sculptures, reliefs and carvings, perpetuated by the numerous plaster casts made and distributed both for research or as works of art in their own right (case in point – the Plaster Court at the Victoria and Albert Museum).

However, this is quite far from the truth. In fact, colour was not only common but of great symbolic importance in Egypt. This is hardly surprising as we use colour to communicate every day even in the modern era (with the most obvious and striking example of the traffic light system, or the wearing of black in many cultures to signal mourning). Although some traditional meanings will have changed over the centuries and varied between cultures, the principle still remains and is widely studied and exploited in a fascinating way in such fields as psychology, marketing and advertising. But I digress…

Let us return to ancient Egypt. To date, many attempts have been made to restore the original colours of artefacts. One such example is the virtual restoration of the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York where experts have a created a colour projection to be overlaid on top of the damaged hieroglyphs. An article on the whole project, called Color the Temple, can be read here.

Some people object to these types of intervention, sceptical of how well they recreate and represent the work of the artist, especially if little physical evidence of the original colours in a particular artefact exists. And indeed, we must always be careful when it comes to any type of restoration to take it only for what it is – someone else’s idea of what the object would have originally looked like (often dependent on the restorer’s skill). Although they might still have a way to go, I personally find these virtual restoration techniques intriguing and full of potential. They certainly help my imagination and understanding of the ancient Egyptian civilisation.

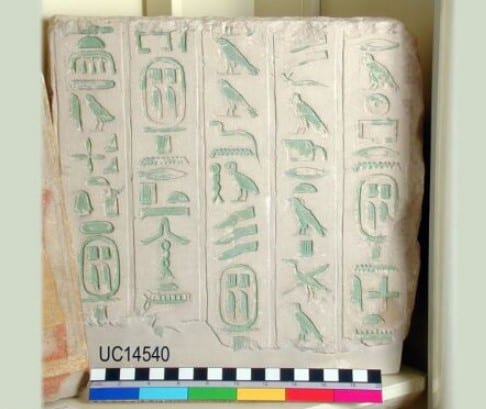

But we can find authentic and undamaged examples of colour even in the Petrie Museum collection. One of the first objects one sees when entering the main exhibition is a limestone wall block fragment from the pyramid of King Pepy I at Saqqara, its beautiful hieroglyphs tinted in green (below).

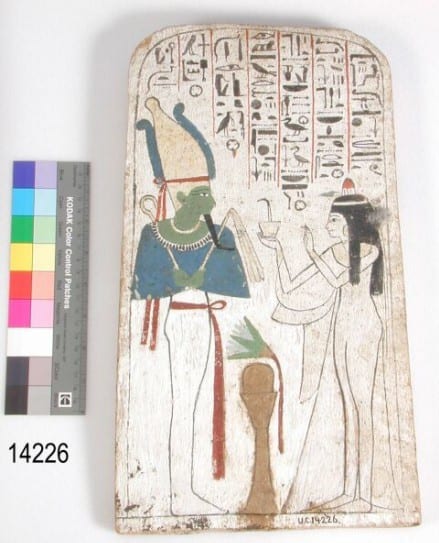

Painted wooden stela of Neskhons, wife of the High Priest of Amun Pinedjem (II) making an offering to Osiris. (Petrie Museum, UC14226)

Painted wooden stela of Neskhons, wife of the High Priest of Amun Pinedjem (II) making an offering to Osiris. (Petrie Museum, UC14226)

While on the other side of the display is a painted, rather than carved, wooden stela of Neskhons, wife of the High Priest of Amun Pinedjem (II) making an offering to Osiris (above).

Egyptian artists would have had at their disposal mostly pigments made from grinding common (as well as some not-so-common) minerals and earths. Hidden away in the Petrie Museum storage is a drawer full of exactly those kinds of pigments (below).

The yellowed typed note reads:

‘The pigments used by the ancient Egyptians for their paintings have been analysed and are mostly made from naturally occurring minerals, finely ground, or from natural substances.

Black – some form of carbon, usually soot.

Blue – originally azurite, a blue carbonate of copper found locally. From the IVth Dynasty on artificial frit was used composed of a crystalline compound of silica, copper and calcium.

Brown – generally ochre, a natural oxide of iron.

Green – powdered malachite (a natural ore of copper), and an artificial frit analogous to the blue frit described above.

Pink – an oxide of iron.

Red – red ochre, a natural oxide of iron.

White – either calcium carbonate (whiting) or calcium sulphate (gypsum).

Yellow – yellow ochre, an oxide of iron and less often orpiment a natural sulphide of arsenic.

The pigments were pounded in to a fine powder, mixed with water to which a little size, gum or albumen was added to make the whole adhesive.’

Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), this subject is too broad and interesting to fit into a single blog post and I’ve decided to explore it further, perhaps expanding beyond Egypt and the ancient times. We shall see where this journey takes me, but I hope you will join me as I investigate individual colours in my future posts.

2 Responses to “Colours of Ancient Egypt – Introduction”

- 1

-

2

Colours of Ancient Egypt – Red | UCL Researchers in Museums wrote on 4 December 2018:

[…] is the third post in the Colours of Ancient Egypt series; here you can read the introduction, and here all about the colour […]

Close

Close

[…] Colours of Ancient Egypt – Introduction […]