by Gemma Angel

by Gemma Angel

In preparation for our upcoming exhibition, Foreign Bodies, several members of the engagement team went to visit UCL Pathology Collections, to have a look at a collection of foreign objects removed from the human body. We soon encountered a number of other specimens which resonated with the exhibition theme in various ways: From a liver infected with syphilis, to a ruptured oesophagus and the sword swallower’s sword that caused the fatal injury; to a feotus inadvertently discovered during a hysterectomy, which was performed to extract a large tumour on the uterus.

The UCL Pathology Collections comprise over 6,000 specimens dating back to around 1850, many of which have been absorbed from other London medical institutions over the past 25 years, and these are currently in the process of being re-catalogued and conserved. It is a fascinating, not to mention an educationally invaluable collection – not least because it contains many specimens that demonstrate gross clinical manifestations of diseases which are now very rare in the Western world. Some of these diseases, such as syphilis, are unfortunately making a comeback, so it seems more important than ever that medical students are able to recognise the clinical signs of these infections. Pathology collections are a highly valuable medical teaching resource; particularly since these kinds of collections are now unlikely to be expanded in the wake of the 2004 Human Tissue Act.

As with many historical pathology collections, UCL possesses its share of medical anomalies or curiosities. Fragments of preserved skin belonging to a tattooed man certainly seem to fall into the category of the anatomically curious – there is certainly nothing pathological about this specimen. One of the biggest surprises I encountered during my visit to the collections, was the revelation that the female reproductive anatomy can, and occasionally does, grow teeth.

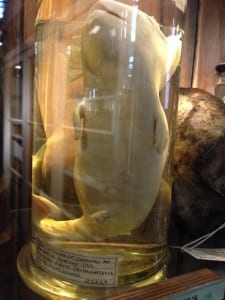

Dermoid cyst (cystic teratoma) with fully developed

tooth and hair. UCL Pathology Collections.

The specimen shown here (right) is a dermoid cyst, or cystic teratoma, which has formed inside an ovary. When I first came across it, I experienced a strong visceral reaction: I didn’t have to be a medical student to recognise that this tooth, entwined in long hair drifting in the liquid-filled vitrine, was out of place – so much so, that the sight of it provoked an immediate and simultaneous sense of revulsion and fascination. The term teratoma is derived from the Greek, tera, meaning monster, and literally means “monstrous growth”; it was easy for me to see how such biological anomalies could become the stuff of nightmares. Despite the ominous name, however, ovarian teratomas are usually benign, and arise from totipotent stem cells which are capable of developing into any type of body cell. One 1941 pathology text describes these tumours as follows:

Dermoid cysts are usually globular in shape and dull white in color. They contain structures associated with epidermal tissues, such as hair, teeth, bone, sebaceous material resembling fat … The following is a partial list of tissues which have been found in dermoids: Skin and its derivatives, sebaceous glands, hair, sweat glands, and bone, especially the maxillae containing teeth. Up to 300 teeth have been found in one cyst … Long bones, digits, fingernails, and skull have been found. Brain tissue and its derivatives, intestinal loops, thyroid tissue, eyes, salivary glands, may occasionally be found. Even rudimentary fetuses have been described, such as a pelvis with hairy pubes and a vulva and clitoris. Brains with ventricles, spinal cords and a few complete extremities, have been observed. [1]

Although teratomas can develop in almost any part of the body – including the brain, neck, bladder, and the testes in men – being confronted with a toothy tumour in the female reproductive organs brought to mind mythic archetypes of the sexually devouring and deadly woman. I was immediately struck by the parallels between this specimen and the image of the vagina dentata. I am not the first to make such an observation,[2] and whilst I am not suggesting that there is any explanatory relationship to be found between the biological phenomena and the myths, it is certainly an intriguing association. The toothed vagina appears in the creation myths and folk stories of many cultures, from Native America, Russia and Japan (amongst the Ainu), to India, Samoa and New Zealand. [3] Funk and Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology and Legend records this entry concerning vagina dentata:

The toothed vagina motif, so prominent in North American Indian mythology, is also found in the Chaco and the Guianas. The first men in the world were unable to have sexual relationships with their wives until the culture hero broke the teeth of the women’s vaginas (Chaco). According to the Waspishiana and Taruma Indians the first woman had a carnivorous fish inside her vagina. [4]

Many 19th and 20th century European interpretations linked the motif to Freudian concepts of castration anxiety, in which young males are said to experience an unconscious fear of castration upon seeing female genitalia. Whilst a Freudian analysis is undoubtedly culturally and historically specific, many vagina dentata legends explicitly articulate male fears of castration in the act of normal sexual intercourse, and warn of the necessity of removing the teeth from women’s vaginas, in order to transform her into a nonthreatening and marriageable sexual partner. A particularly telling collection of stories comes from India, in which the ferocious sexual appetites of beautiful young women are tamed and ‘made safe’ to men through the violent breaking of the teeth hidden inside their vaginas. [5]

Māori wood carving of the goddess Hine-nui-te-pō and Māui.

Photograph by Charles Augustus Lloyd, c.1880s-1912.

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

The toothed vagina motif is not exclusively associated with male fears of the ‘castrating female’, however. In some traditions, the terrible power of the vagina dentata lies principally not in fears of the sexual act, but in its associations with death. The Māori legend of Māui and Hine-nui-te-pō is particularly interesting in this respect. Hine-nui-te-pō was the goddess of death and gatekeeper of the underworld, whom the trickster demigod Māui sought to kill in order to win immortality for humankind. When Māui asks his father what his ancestress Hine-nui-te-pō is like, he responds by pointing to the icy mountains beneath the fiery clouds of sunset. He explains:

What you see there is Hine-nui, flashing where the sky meets the earth. Her body is like a woman’s, but the pupils of her eyes are greenstone and her hair is kelp. Her mouth is that of a barracuda, and in the place where men enter her she has sharp teeth of obsidian and greenstone. [6]

Undeterred by his father’s grave warnings, Māui sets off on his quest with a gathering of bird companions. He proposes to kill Hine-nui-te-pō by entering her vagina and exiting through her mouth whilst she is sleeping, thus reversing the natural passage into life via birth. Māui finds the great goddess sleeping “with her legs apart” such that they can clearly see “those flints that were set between her thighs”, and he transforms himself into a caterpillar in order to crawl through her body. But his bird companions are so struck by the absurdity of his actions, that they laugh out loud and wake Hine-nui-te-pō from her slumber. Angry at Māui’s impiety, she crushes him with the obsidian teeth in her vagina; thus Māui becomes the first man to die and seals the fate of all humankind, who were ever after destined to die and be welcomed into the underworld by Hine-nui-te-pō. In this version of the myth, the vagina dentata appears as an inverse manifestation of the generative, life-giving powers of woman, which Māui attempts to subvert – he endeavours to overcome the forces of life and death, and therefore “by the way of rebirth he met his end.” [7]

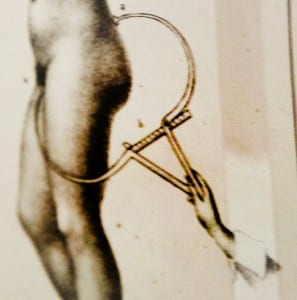

X ray of a dermoid cyst, showing a cluster of teeth in the pelvic cavity.

The mythical theme of the vagina-with-teeth can in most cases be read as an attempt to render the potentially dangerous sexuality of women nonthreatening to patriarchal power, through heroic acts of “pulling the teeth”. Some authors have even suggested a correspondence between this mythic construct and practices of clitoridectomy and ‘female circumcision’ in some cultures. [8] Whilst there can be little correlation between ancient stories and the observation of biological phenomena such as dermoid cysts, the removal of these peculiar tumours and their retention in pathology collections nevertheless reminds us of the remarkable complexity and diversity of human understandings of the body, and their wider cultural significance. For those readers interested in the practical removal of teratomas such as those discussed here, a demonstration of the surgical procedure can be viewed in this educational film (contains scenes of graphic live surgery).

References:

[1] Harry Sturgeon Cross and Robert James Crossen: Diseases of Women, St. Louis (1941), p.685.

[2] See, for example, Bruce Jackson: ‘Vagina Dentata and Cystic Teratoma’, in The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 84 No. 333 (July-Sept 1971), pp.341-342. Available on JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/539812

[3] Verrier Elwin: ‘The Vagina Dentata Legend’, in British Journal of Medical Psychology, (1943) Vol. 19, pp. 439-453.

[4] Maria Leach (ed): Funk and Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore Mythology and Legend, Volume 2 J-Z (1950), p.1152.

[5] Verrier Elwin: ‘The Vagina Dentata Legend’, in British Journal of Medical Psychology, (1943), Vol. 19, pp.439-453. A particularly illustrative example of one of these stories is recounted by Elwin on pp.439-440:

There was a Baiga girl who looked so fierce and angry, as if there was magic in her, that for all her beauty, no one dared to marry her. But she was full of passion and longed for men. She had many lovers, but – though she did not know it – she had three teeth in her vagina, and whenever she went to a man she cut his penis into three pieces. After a time she grew so beautiful that the landlord of the village determined to marry her on the condition that she allowed four of his servants to have intercourse with her first. To this she agreed, and the landlord first sent a Brahmin to her – and he lost his penis. Then he sent a Gond, but the Gond said, “I am only a poor man and I am too shy to do this while you are looking at me.” He covered the girl’s face with a cloth. The two other servants, a Baiga and an Agaria, crept quietly into the room. The Gond held the girl down, and the Baiga thrust his flint into her vagina and knocked out one of the teeth. The Agaria inserted his tongs and pulled out the other two. The girl wept with the pain, but she was consoled when the landlord came in and said he would now marry her immediately.

[6] Antony Alpers: Maori Myths and Tribal Legends, Pearson Education, New Zealand (1964), p.67.

[7] Ibid, p.70.

[8] See for example, Jill Raitt: ‘The “Vagina Dentata” and the “Immaculatus Uterus Divini Fontis”‘, in Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 48 No. 3 (Sept. 1980), pp.415-431. Available on JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1462869

[analytics-counter]

Filed under Foreign Bodies Exhibition, Gemma Angel, Museum Collections, Museum Trail, UCL Collections, UCL Exhibitions

Tags: castration anxiety, Hine-nui-te-pō and Māui, Māori myths, mythology, ovarian dermoid cysts, pathology, reproductive anatomy, Sigmund Freud, surgery, teratomas, tumours, UCL Pathology Collections, vagina dentata

15 Comments »

Last Saturday I was engaging at the Grant Museum of Zoology where I started talking with two visitors about the history of science. As a Victorian historian, my doctoral research specifically looks at the historyof Victorian medicine and its relationship to women and the articulation of the healthy female body. There couldn’t be a better setting to discuss those themes than the Grant Museum- the only remaining zoological university collection in London, which houses a dizzying array of zoological specimens dating back to the early nineteenth-century. The museum’s founder, Robert Edmond Grant, is particularly known for his influence on the young Charles Darwin, when the latter studied under him at Edinburgh University.

Last Saturday I was engaging at the Grant Museum of Zoology where I started talking with two visitors about the history of science. As a Victorian historian, my doctoral research specifically looks at the historyof Victorian medicine and its relationship to women and the articulation of the healthy female body. There couldn’t be a better setting to discuss those themes than the Grant Museum- the only remaining zoological university collection in London, which houses a dizzying array of zoological specimens dating back to the early nineteenth-century. The museum’s founder, Robert Edmond Grant, is particularly known for his influence on the young Charles Darwin, when the latter studied under him at Edinburgh University.

Close

Close