Incest in Nature

By Alexandra Bridarolli, on 20 December 2018

This is the third segment in a series on incest; you can go back and read the previous segments on incest in ancient Egypt and incest in the Hapsburg family.

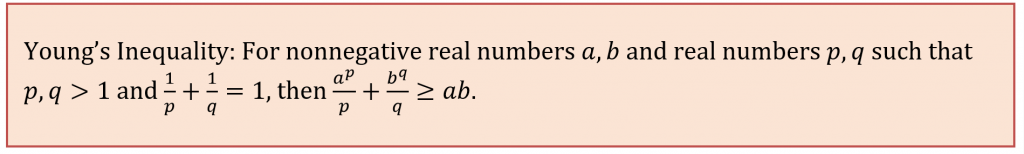

Firstly, did you know that despite the earliest forms of life emerging around 3.8 billion years ago, sex has only existed for 1.2 billion years? Before that, asexual reproduction was the only form of reproduction to evolve. When you think about it, this is the most extreme type of incest, reproducing yourself with …yourself, cloning yourself. Nowadays, most mammals tend to not engage in inbreeding. If they do, we have seen that incest can lead to depression inbreeding with offspring experiencing health problems. For this reason, scientists used to think that Nature might have weeded out incestuous behaviour through natural selection.

However, recent studies have actually shown that incestuous behaviour has not completely disappeared and that it is more common than generally thought. Some species are asexual or still breed with themselves in situations where there is no advantage to sex; others commit incest where there is no penalty to inbreeding. And guess where those incestuous species are mostly found? Islands and mountaintops. In these isolated places, it is difficult to find someone who does not fit somewhere in your family tree.

Incestuous species

- Mongoose

Mongoose live in close-knit groups with a median size of 18 adults. Each group has both male and female dominant members, who do most of the breeding and reproducing—those on the periphery only reproduce occasionally. Most group members remain with their group for their entire lives. This close-knit living arrangement has led to a high incidence of incest. A study has found that 64% of newborn pups were the result of mating between members of the same natal group (Nichols, 2014). Father/daughter incest was documented eight times over the course of the study run over 16 years; no mating attempts between mother/son were reported. The researchers point out that females tend to have short lives and generally die before their sons are old enough to mate with them.

Yellow mongoose, Cynictis penicillata

- Whiptail lizards

This one is with no doubt my favourite.

Some women might have dreamed of a world with no men. Whiptail lizards have done it. Females whiptail lizards are able to clone themselves. And this is not the only species with this capability. There are actually quite a few, 80 groups to be precise, which include amphibians, reptiles, and even fish. But the specificity of these female lizards is that though they don’t need to have sex to survive, they still display mating behaviours, meaning that females sometimes mount other females. Scientists think this behaviour is hormonally driven; high progesterone levels may cause females to mount others. But they probably don’t just bump cloacal regions for fun. Studies have shown that females who are mounted by another female are more fertile than those who go it alone, likely because the mounting behaviour promotes ovulation (Wade, 2013).

Mating behaviour among whiptail lizards: female lizard mounting another female.

- Spotted salamanders

Among spotted salamanders, DNA analysis shows inbreeding at the level of first cousins, on average. Despite having hundreds of possible mates to choose from, females tended to fertilize their eggs with sperm from related males.

Spotted salamander

Interestingly, in some cases, the natural selection mentioned earlier seems to contradict other studies showing that for some animal or insects, inbreeding within first cousins or brother/sister gives better chance of survival to the offspring. Inbred ambrosia beetles, for example, fared no worse than outbred insects, and the eggs produced by brother-sister pairs are likelier to hatch than the eggs of unrelated pairs (Andersen 2012). Similarly, another study has found that for at least one fish species, fathers from brother-sister couples spent more time, on average, defending their caves and that both parents tended to pay more attention to their kids than unrelated couples.” How to explain this? The ecologist who supervised the study reports, “Couples which are full siblings are more cooperative in brood care. … [T]he males and females stay with the offspring for several weeks and guard them—they defend them—and there’s less aggression between full siblings.”

Stay tuned for next and final segment in a series on incest. We will talking about the practice of incest in modern societies: Modernization or cultural maintenance?

References

Andersen, H., Jordal, B., Kambestad, M., & Kirkendall, L. (2012). Improbable but true: The invasive inbreeding ambrosia beetle Xylosandrus morigerus has generalist genotypes. Ecology and Evolution, 2(1), 247-257.

Nichols, H., Cant, M., Hoffman, J., & Sanderson, J. (2014). Evidence for frequent incest in a cooperatively breeding mammal. Biology Letters, 10(12), 20140898.

Wade, J., Huang, J., & Crewst, D. (1993). Hormonal Control of Sex Differences in the Brain, Behavior and Accessory Sex Structures of Whiptail Lizards ( Cnemidophorus Species. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 5(1), 81-93.

Close

Close