‘Writing the Law’ Launches at Lambeth Palace Library

By Arendse I Lund, on 12 June 2019

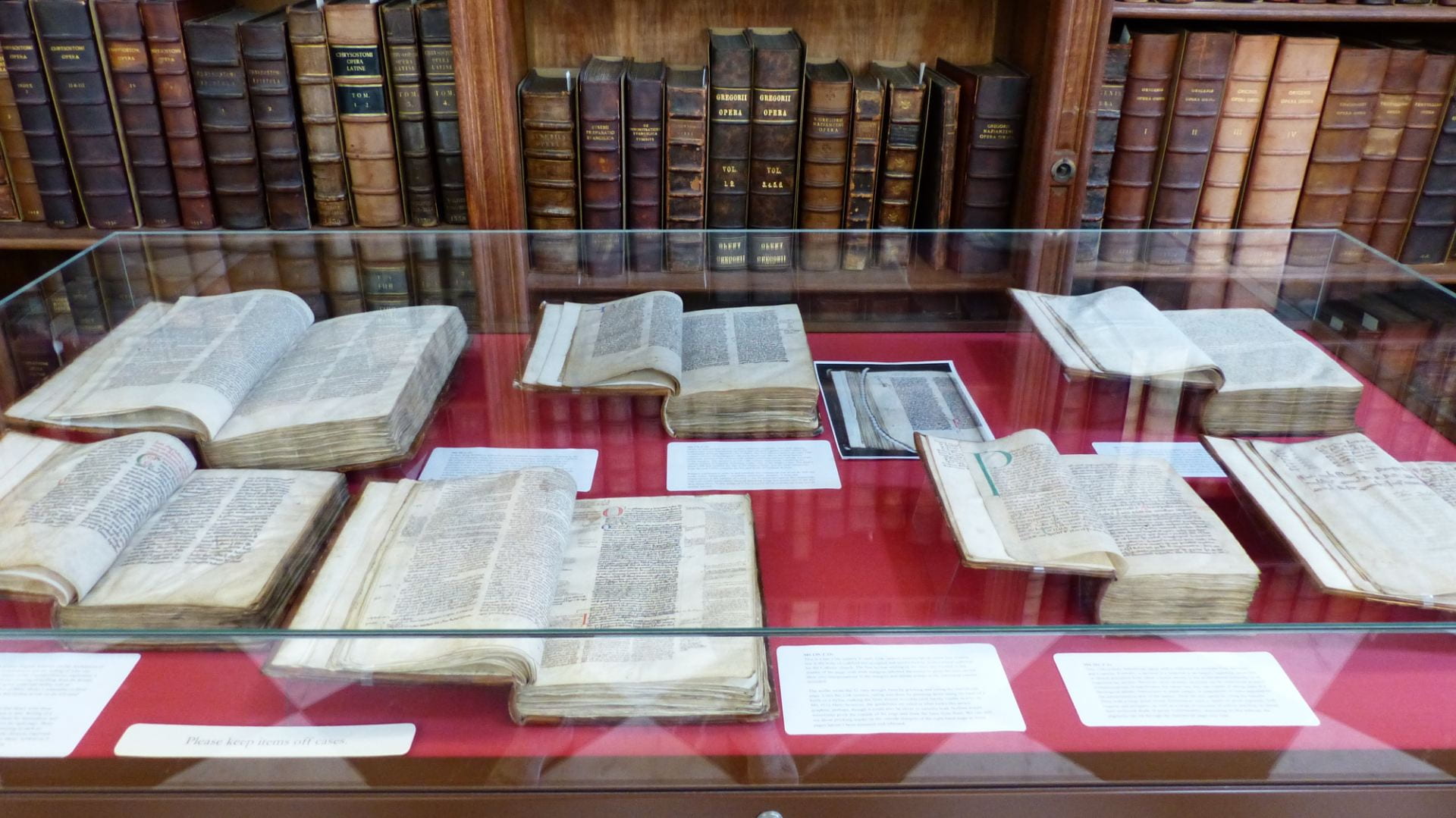

This week, I launched “Writing the Law: Lambeth’s Legal Manuscript Collection,” an exhibition of medieval legal manuscripts I curated for Lambeth Palace Library. The exhibition was supported by the London Arts & Humanities Partnership and stems from my research in the UCL English Department.

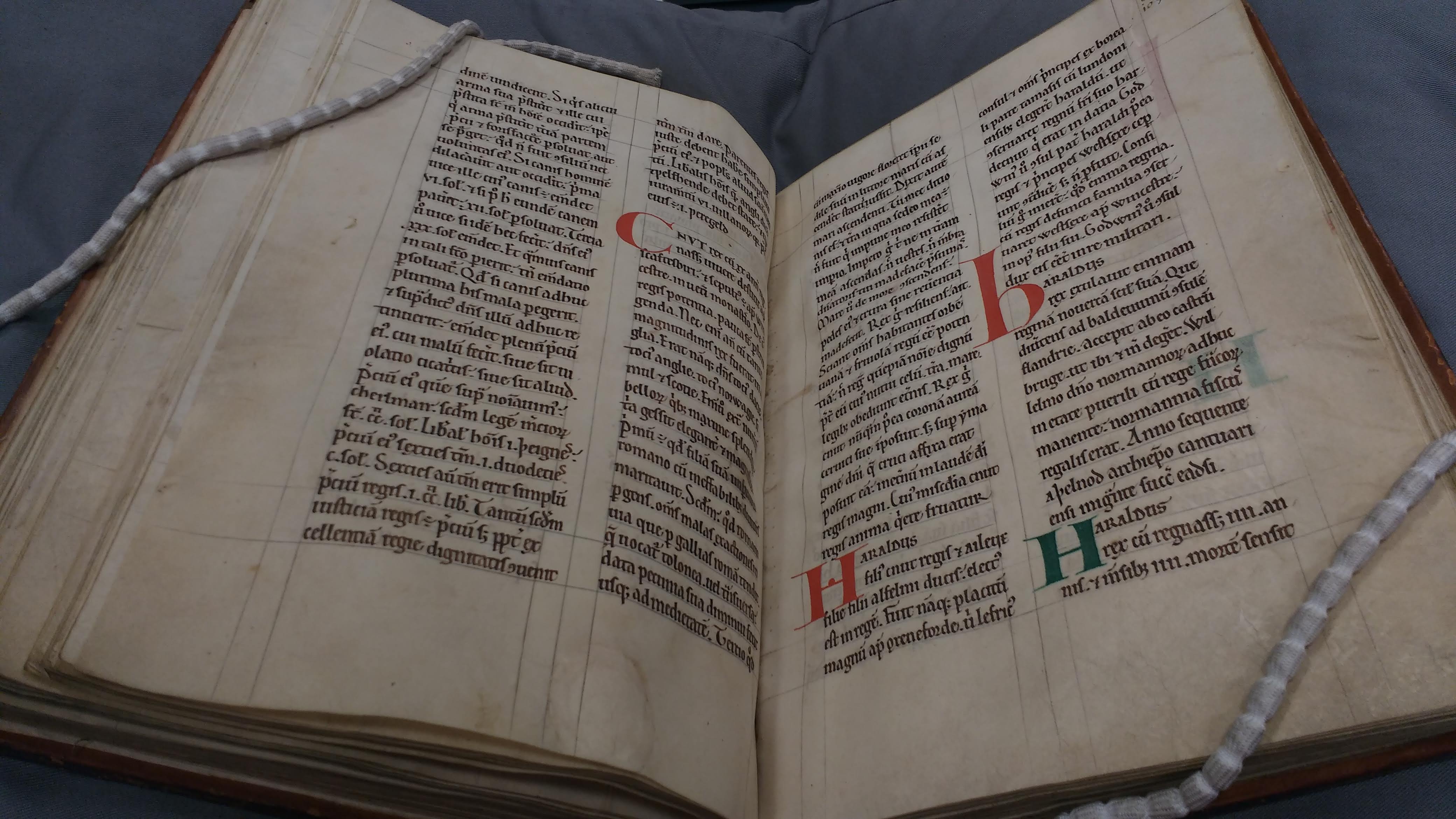

“Writing the Law: Lambeth’s Legal Manuscript Collection” is on display at Lambeth Palace Library (Image: Camille Koutoulakis)

Lambeth Palace was founded in the Middle Ages as the seat of the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the many centuries since then, each Archbishop added to the library’s holdings, either through explicit collections and purchases of manuscripts and books, or by leaving their own books and papers for posterity. The manuscripts on display as part of the exhibition entered into the Lambeth Palace Library collection at different times and thanks to the collecting interest of different archbishops. But they all shed light on how law was produced, written down, and evolved throughout the Middle Ages.

This exhibition comes out of my doctoral research on medieval law — specifically how rulers used law as a type of propaganda to increase perceptions of their own authority. Lambeth has generously given me the space to explore this topic in their collections and I thought I’d take a few paragraphs to write about some of the perhaps less obvious manuscripts on display and what they tell us about medieval law.

When we think of law, we often think of things that we consider strictly legal documents: legal treatises, or wills, land grants, maybe writs forbidding someone to act in a certain way. There are certainly many of these types of manuscripts on display. One of the highlights is a 13th-century copy of Lombard law, listing the amount of compensation you’d need to pay if you injured someone. Another highlight is a 14th-century copy of the Magna Carta. But we also have to take into account the many documents that shed light on the social and cultural history behind legal change.

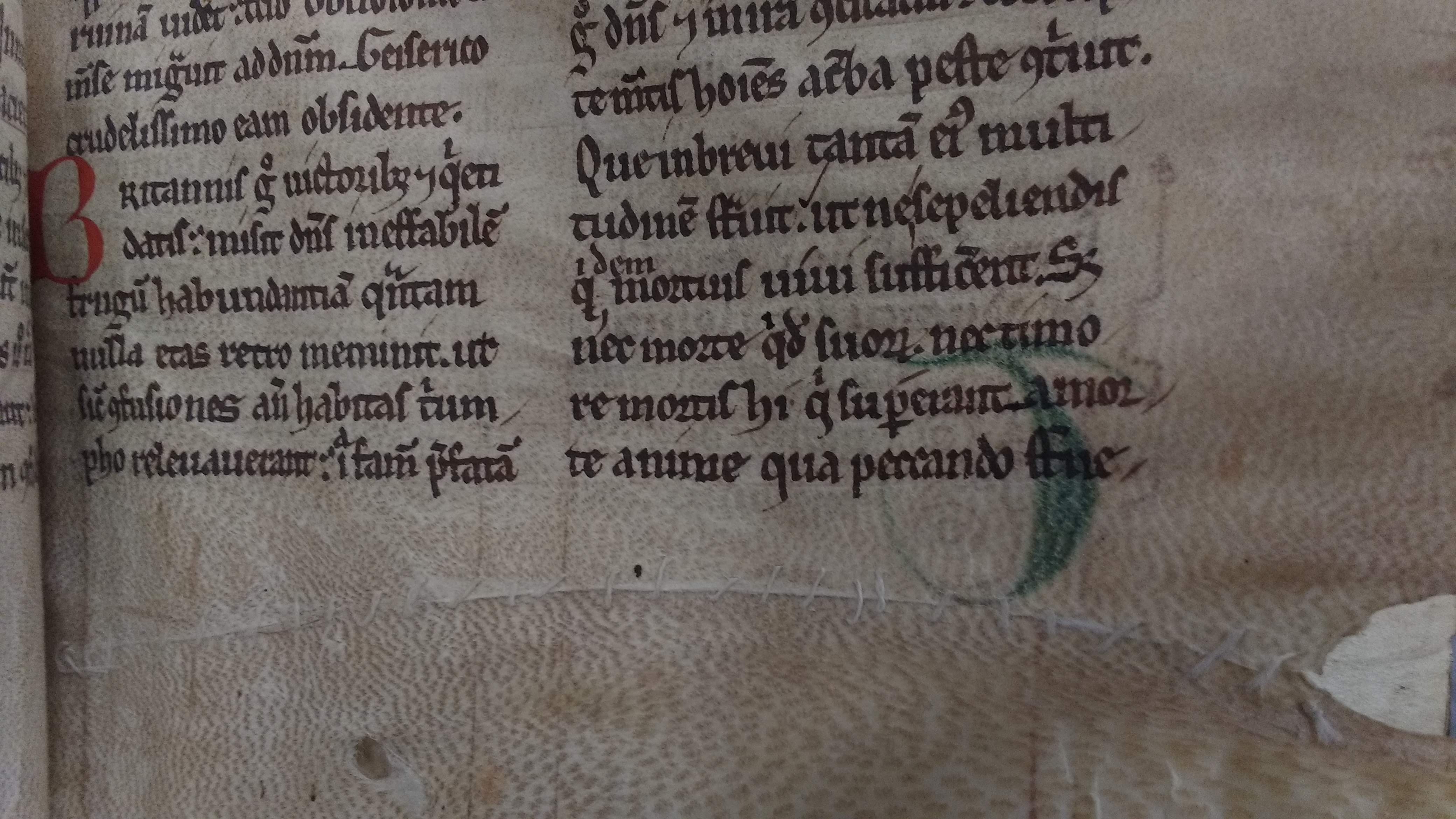

Two of Lambeth Palace Library’s early versions of Henry of Huntingdon’s ‘History of the English’ (Historia Anglorum) are on display. Henry of Huntington was a 12th-century historian and the archdeacon of Huntingdon. His greatest accomplishment was the writing of what was supposed to be a single book on the history of the English but which spiraled out into multiple volumes detailing the lives and reigns of the English kings. One of the Lambeth Palace Library versions contains heavy reader annotations and marginalia. These are in many ways entirely different from the more formal types of commentary provided by the glosses to the canon law displayed nearby; and yet, these sorts of reader interactions with the text give us modern historians an understanding of how law was interpreted by its contemporaries.

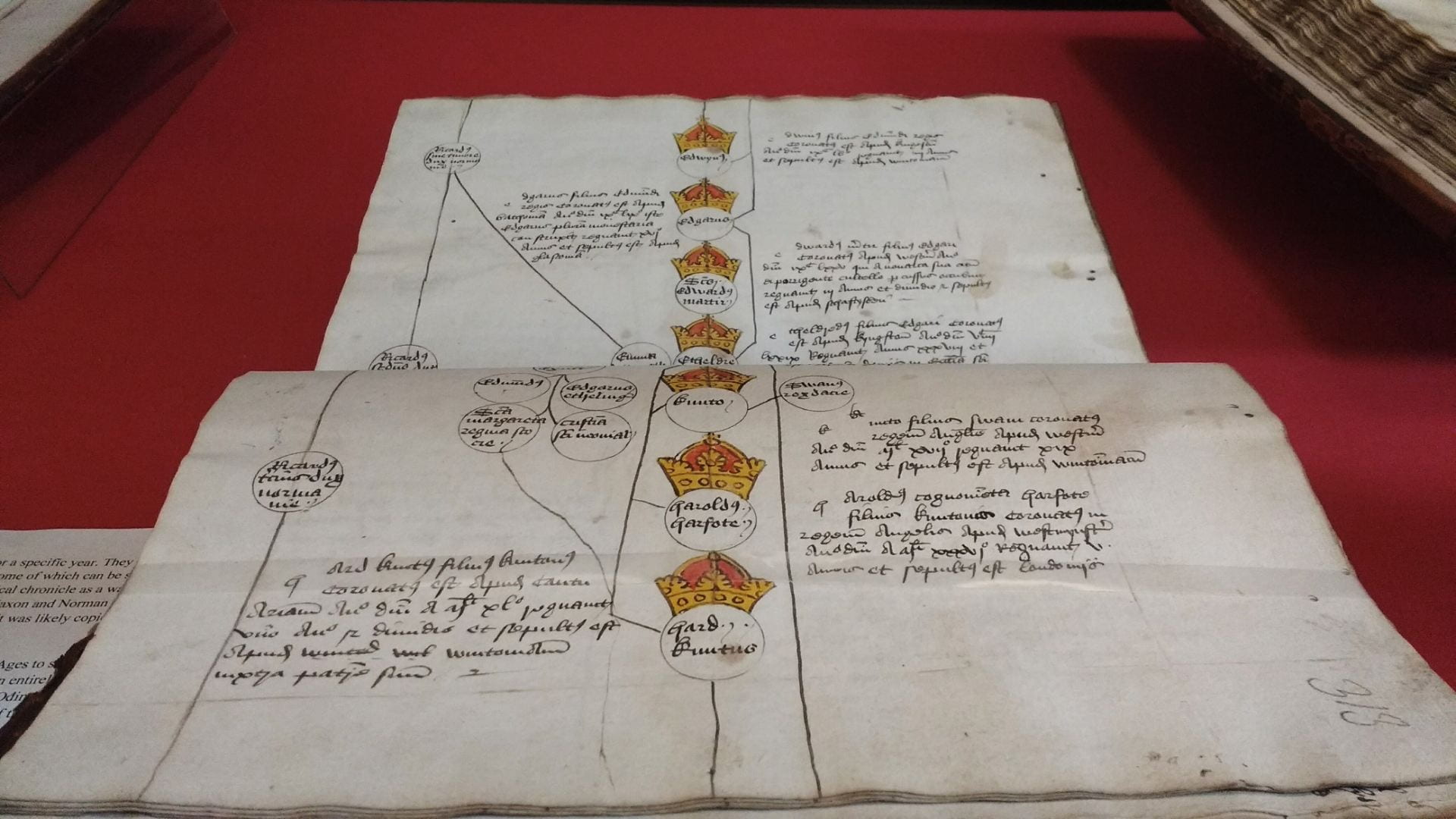

This Year Book [Lambeth Palace Library MS 270, f. 313r] includes a genealogical chronicle as a way of emphasizing Henry V’s descent from both Anglo-Saxon and Norman royal dynasties, in addition to prominent Biblical figures (Image: Arendse Lund)

Since my research interests lie with royal propaganda, one of the stars on display is a royal family tree. It lists the genealogy of all the kings of England, which some inventive scribe has managed to connect altogether. The genealogy starts with Irad, the Biblical son of Cain, and winds its way through famous figures, eventually getting to the Anglo-Saxon kings, including Alfred the Great, and then continuing past the Conquest, ending with King Henry V. There are approximately 40 roll chronicles of this type that survive from the later Middle Ages, many held by the British Library. Royal descent, traced through these frequently-invented blood relationships, was a powerful tool used to legitimize the succession of power and promote dynastic identities. But, one of the first things you’ll notice looking at the genealogy that on display at Lambeth Palace Library, is that it is very much a hefty manuscript and not a roll. But we can tell that it was likely copied from one of these rolls because a confused scribe has turned the manuscript sideways to draw in the family tree, in an attempt to mimic the roll form and try to maximize space. So, in following the scribe’s efforts, I too have displayed the manuscript sideways.

Although I could happily go on to describe each manuscript on display, I better stop there. I would like to end by issuing a huge thank you to Lambeth Palace Library for being generous with their space, and in particular, Dr Rachel Cosgrave, Senior Archivist, and Giles Mandelbrote, Librarian and Archivist, for their support.

You can go see “Writing the Law: Lambeth’s Legal Manuscript Collection” at Lambeth Palace Library this summer. Although generally closed to the public, you can view the exhibition during the Open Days; the next one is 5 July.

Close

Close