Louis Arnaud Reid: Philosopher, Educator, Artist

By Kurt Jameson, on 11 December 2019

One of my first tasks as a project archivist at UCL has been to catalogue the papers of the philosopher and educator Louis Arnaud Reid. Reid became the first Professor of Philosophy at the Institute of Education, and was a strong advocate of the importance of art in education. He retired in 1962, but continued writing and teaching as an emeritus professor right up until his death in 1986 at the age of 90. These papers were donated by his widow Molly.

The first thing that strikes you about the papers of Louis Arnaud Reid is the sheer volume of work. We have his drafts of 48 articles, papers, and books that he wrote. Draft after draft is typed, annotated with notes, and immaculately Tippexed. Here is someone who must have sat at his typewriter for hours on end, day after day. And this went on for decades – Reid published his first article in 1922, and his final book was published in 1986.

This photo of Reid was probably taken around 1940 or 1950. Despite looking very serious here, his correspondence hints at someone who was warm and affectionate. Below is an extract of a letter he wrote to a friend to ask for help in editing one of his books. He finished the letter by signing off:

“I know you’re enormously busy, and am really sorry to make it worse. I do wish we could meet sometimes. If it would save your time I could come to Cambridge; but I think it would probably have to be by train.

‘Thanking you in anticipation’ (as they say)

and very much love (as I say!)

Louis”

As for Reid’s contribution to the fields of philosophy, education and art – his colleague Tony Dyson summarised his work in an article shortly before Reid’s death:

“What is perhaps most remarkable about Louis Arnaud Reid’s life’s work is its consistency: he was writing about feeling and knowledge in the 1920s – and this is still his major preoccupation. The fact that his ideas have been assimilated and frequently employed – consciously or otherwise – by other apologists for the arts is clear evidence of the effectiveness of his mission. He has provided us with a formidable armoury in defence of the arts in education and, in so doing, he has ‘made philosophy live’ for very, very many, far beyond the immediate circle of his students and colleagues.”

Article in ‘Alumnis, The Review of the Institute of Education Society’ (1985)

Reid’s friend and peer Harold Osborne has also written that Reid was “clear that the central purpose of education should be the enrichment and development of the personality as a whole, and this must include the enhancement and honing of that power of direct apprehension which can never be wholly accommodated within verbal propositions” (quoted in Reid’s obituary in The Journal of Art & Design Education, written by Sheila Paine).

Amongst his papers, Reid has also retained material from his seminars at the IOE. Reid’s teaching methods with students are demonstrated here in his typed seminar questions for his students, and students’ written reports from each seminar group discussion have also been kept. His love of art is also clear from two sketchbooks which include Reid’s sketches in watercolour, crayon, and pencil, including the picture below:

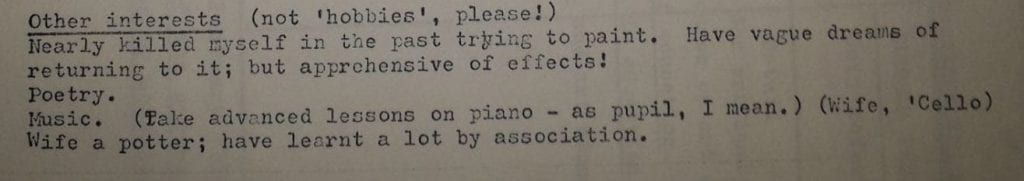

However, his self-written bio for the department at the IOE includes the note:

“Nearly killed myself in the past trying to paint. Have vague dreams of returning to it; but apprehensive of effects!”

Overall, between the many typed drafts of articles and book chapters, the notes from his taught seminars at the IOE, and Reid’s own handwritten notes, there is likely to be much of interest here to a researcher of the philosophy of art and education, and how the two should be combined.

Update

After writing this blog, I later catalogued a small, additional amount of ‘oversize’ material that had been included in Reid’s papers and stored separately, and its content was a little unexpected. It consisted mainly of photographs and pupils’ schoolwork from the Romford County High School for Girls, dating from 1907 to about 1946. Louis Arnaud Reid was never a teacher or a pupil at this school, and would have been only 12 years old in 1907. How, then, did he come to possess this material?

Romford County High School for Girls was founded in 1906 by Frances Bardsley. The school today is known as The Frances Bardsley Academy for Girls, and its website provides some background on her, along with some photographs:

https://fbaok.co.uk/history-of-frances-bardsley/

Frances Bardsley graduated from London University in 1895 and then trained to be a teacher at the Cambridge Training College. At this time, when women had very limited opportunities, it would have been quite rare for a woman to achieve this level of academic education, and to pursue this career path.

Looking through these papers, you get a sense of the activities carried out at the school, under Bardsley’s time there. Decorated ‘Form Book’ folders contain colourful drawings and paintings, poems, and short stories which are often annotated with sketches, all created by the pupils. Programmes of school events reveal festival days at the school, which included activities such as drama, tableaux, choir singing, ‘moving pictures’, recitations, written articles, band performances, cooking, drawing, flower pressing, and dress making. Prizes were given in each category, and guests were sometimes invited, for example Elizabeth Hughes (Bardsley’s former mentor at the Cambridge Training College) and Sophia Bryant (the first woman in Britain to earn a science doctorate).

It seems fairly clear that these papers once belonged to Frances Bardsley. It is not at all clear how they came to be in Louis Arnaud Reid’s possession, however he may have acquired and kept them due to the way they vividly demonstrate how art, poetry, drama, music, and fun can be used in education. Frances Bardlsey lived until 1952 (aged 80), at which point Reid had already been teaching at the IOE for five years, so it is possible that the two met at some point to discuss their ideas and experiences regarding education and the arts.

The catalogue for Louis Arnaud Reid’s papers (including the material from the Romford County High School for Girls) can be viewed online here.

Close

Close