George Greenough’s papers – a window into the worlds of 19th-century science, wealth, and empire

By Kurt M Jameson, on 28 October 2022

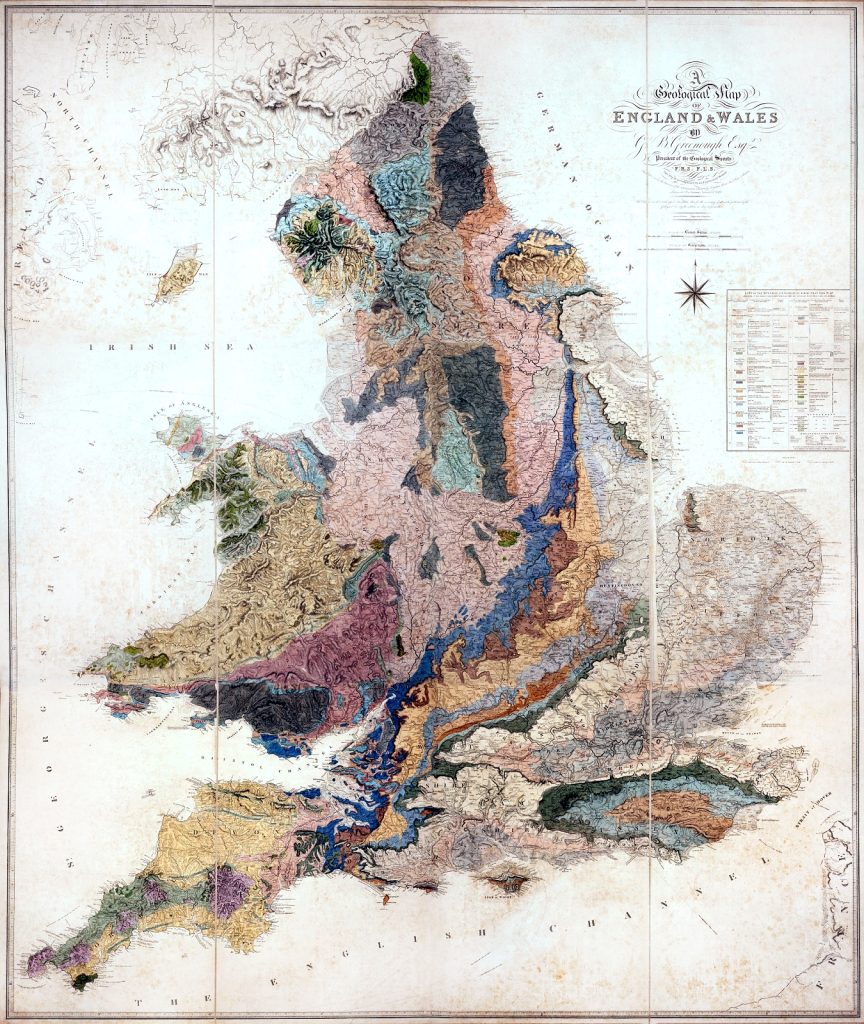

George Bellas Greenough inherited a fortune at the age of 16 and, as a rich man in his 20s, decided to devote his life to the study of geology. He is best-known for his Geological Map of England and Wales, published in 1820, which used new data and an innovative colouring system to highlight deposits of different types of rocks and minerals. He later became a controversial figure due to his clashes with William Smith, another geologist who had also made a very similar geological map at almost exactly the same time.

Greenough’s Geological Map of England and Wales, published in 1820 by the Geological Society. An original copy of his 2nd edition, published in 1839, is held at UCL Special Collections (GREENOUGH/A/2/1).

In the title of Simon Winchester’s book The Map that Changed the World (2001), he is referring to the map created by Smith. Winchester claims that Greenough plagiarised Smith’s map, and that Greenough was an elitist snob who blocked Smith’s entry to the Geological Society due to his class background. However, others have since argued that the creation of Greenough’s map was in reality more nuanced.

Portrait of Greenough by Maxim Gauci, mid-19th century. Held at the National Portrait Gallery.

Regardless of whether or not Greenough plagiarised Smith’s work, these maps were ground-breaking in the way that they displayed the minerals and resources that were lying under the ground. This was an exciting development not only for those with an interest in geology or the study of fossils, but also to those who stood to benefit financially. At the time, raw materials were in high demand in order to fuel the industrial revolution. In Simon Winchester’s words: “Landowners realized that they possibly had beneath their lawns, meadows and forests huge seams of coal that could make them rich beyond their dreams.”

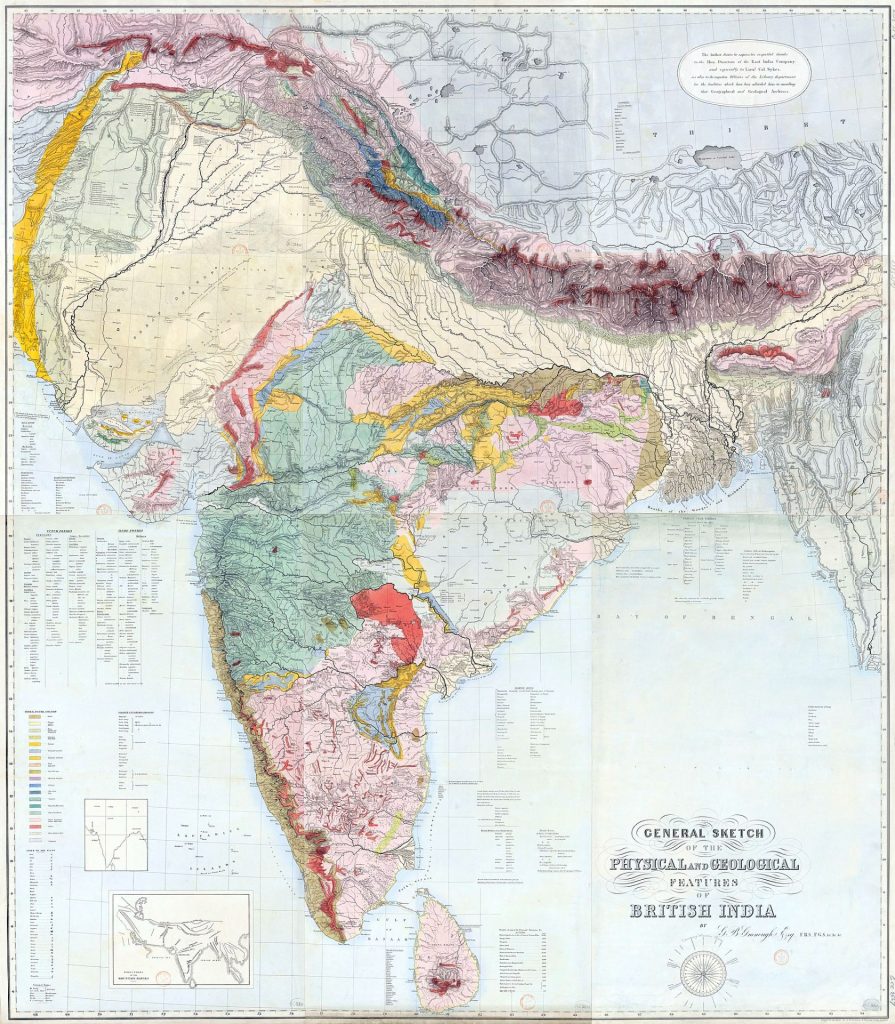

This was also a time of a growing British Empire, which may explain why Greenough’s other major publication was a comprehensive geological map of ‘British India’, in 1855. Greenough produced this map with the help of the East India Company, but never visited the Indian subcontinent himself. Some of Greenough’s papers hint at the potential advantages for nations of having more accurate geological information. The following passage is from a draft letter of 1810 which appears to have been drafted or translated by Greenough for Jacques Louis, Comte de Bournon, regarding a collection of minerals that had recently been bought by the British Museum:

“The collection of the late Mr. Greville, celebrated throughout Europe, is now the property of Great Britain, a country the commerce manufactures & territorial revenue of which are intimately connected with the state of its mines & this acquisition has been made at a time when mineralogy engages a more than ordinary share of public attention.” (GREENOUGH/B/4/R/12)

Greenough’s General Sketch of the Physical and Geological Features of British India, published in 1855. An original copy is held at UCL Special Collections (GREENOUGH/A/3/1).

UCL Special Collections holds a substantial collection of George Greenough’s papers. These papers include original copies and fragments of his own geological maps, his notes on various geological topics and debates, and his notes on other sciences. His diaries from his many expeditions through Europe include descriptions and sketches of the surrounding geology, as well as his observations on the local culture and politics. In one of these diaries he describes his escape from Sicily in 1803, as the French had invaded the Italian peninsula from the north (GREENOUGH/B/2/1/1).

A considerable amount of these papers consist of Greenough’s private correspondence. These letters read like a ‘who’s who’ of the elite scientific community in 19th-century Britain, and include letters from Michael Faraday, Francis Beaufort, Marc Isambard Brunel, and John Herschel. Being from this time period Greenough’s correspondence is almost entirely with other men, although there are some letters from women. In one letter Sarah Frembly appealed to Greenough to use his influence with the Admiralty, as her husband John had been shipwrecked and dismissed from the Royal Navy, leaving her family destitute (GREENOUGH/B/4/F/14).

In later life Greenough also focussed on the field of geography, serving as the President of the Royal Geographical Society from 1839 to 1841. This likely explains why he was in possession of a leaflet for a rescue mission for Franklin’s lost expedition to find the ‘Northwest Passage’ through the Canadian Arctic (GREENOUGH/B/3/5/1), and of prospectuses for the construction of a ‘Grand Georama’ in London (GREENOUGH/B/1/10).

The Greenough papers arrived at UCL in two separate deposits, the second deposit of which (‘Part B’) is newly-catalogued. The catalogue for the Greenough papers can be browsed via the UCL Archives online catalogue: https://archives.ucl.ac.uk/CalmView/. The Greenough papers will be of particular interest for any researchers of the history of geology, but may also prove useful for research into other aspects of 19th-century Britain.

To make an appointment to view any of the papers in the Greenough collection, please contact us at spec.coll@ucl.ac.uk.

Close

Close