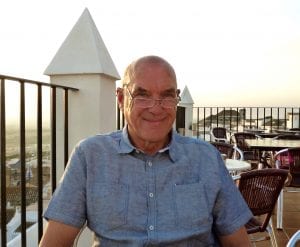

Gone but not forgotten: Fred Bearman, Preservation Librarian

By ucylgmf, on 27 January 2017

The moving piece below was written jointly by Fred’s partner, Fred himself, and Tabitha Tuckett, and has been made available for us to share here, along with the image.

Fred Bearman (13 December 1949 – 11 December 2016)

Fred Bearman was a leading educator in rare books and archives who, in a remarkable career that spanned half a century, inspired generations of conservators, librarians, archivists, students and members of the public in the UK, across Europe, in the USA and beyond.

Born in 1949 in Essex, he began his career at the age of 16 as a trainee conservator at the Public Record Office in London (now The National Archives). Taking courses on day-release at Camberwell College Of Arts and the London College Of Printing, in addition to the in-house training programme, he soon became Senior Conservator. He was to work there for 26 years, for many of which he supervised the central London conservation studio, focusing on the conservation needs of The National Archives’ pre-1800 books.

Fred’s work involved some of the UK’s most iconic manuscripts: he was part of the team that rebound Captain Bligh’s log-book from HMS Bounty, not to mention the conservation of Magna Carta, and he was presented to HRH Queen Elizabeth II in recognition of his work on the Domesday Book for its 900th anniversary. He also began, at The National Archives, to demonstrate the skills as a leader and communicator that were to distinguish his later career: he devised a new conservation-training programme, and set up a survey of historic book-bindings and book-structures, the result of which was the establishment of a handling and preservation policy for The National Archives.

From 1990 Fred acted as Preservation Advisor to the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC. There he conserved the Folger’s renowned collection of Shakespeare’s first folios (all 92 of them), and catalogued many of the library’s fine bindings, work that culminated in his co-curating a significant exhibition and co-authoring its catalogue.

In 1992 he moved to the USA full-time as Head of Conservation and Collections Care at Columbia University Libraries, New York, where he took responsibility for conservation across all twenty-nine of the University’s libraries, and was also involved in a major conservation project of early bibles and the historic Hussite Gradual Hussitussite graduat Chelsea Theological Seminary, NY, as well as acting as consultant for Christie’s and many other organisations.

Returning to the UK in 1997, Fred Bearman became Director Of Conservation at Camberwell College Of Arts. As Course Director for BA and MA courses, his authoritative but warm and encouraging teaching style inspired a new generation of book conservators in the UK, as it had earlier at The National Archives and in the USA. He was to maintain his links with fresh intakes of Camberwell conservation students for the rest of his career.

It was during this period that Fred established the preservation programme for the library of the Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai, Egypt, the world’s oldest continuously operating library, work that Nicholas Pickwoad subsequently took on. Fred was also engaged as a preservation adviser to several EU-funded projects, including at Mekerere University Library and Archive Collections in Kampala, Uganda. There, in addition to giving advice, he provided on-site training for staff. Back in the UK, Fred maintained a serious commitment to supporting training in the profession, and became Assessor for the Professional Accreditation for Conservator-Restorers (PACR) of Icon, the Institute of Conservation.

He also maintained his work at the bench. From 2004 until 2006, he worked as Rare-Book Conservator in the Book & Paper Conservation Studio, Dundee University Library, treating material of great international significance that came into the studio from libraries, archives and private collections across the UK. Fred also worked with book conservator Lizzy Neville at her Kentish Town studio, acted as consultant on the Iveagh Bequest at English Heritage’s Kenwood House in London and for the library of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, and worked as Head Of Conservation at Shepherds in London, one of the oldest bookbinding companies in England.

In 2007 Fred moved to University College London as Preservation Librarian across the University’s many libraries. These included one of the foremost university collections of rare books, manuscripts and archives in the south of England, and Fred spent the rest of his life researching, teaching and writing on these historic collections, while managing the Library Services’ preservation and conservation needs. The latter included the move of over 600,000 rare items into temporary storage at The National Archives to facilitate building plans. This project illustrated Fred’s prodigious gifts as a natural leader and communicator: only he could have persuaded over 100 volunteers that wrapping seemingly endless quantities of books in archival paper – a requirement of the move – was both important and a privilege. And he did so with such fascinating insights into the unique historical collections being wrapped, and took such an interest in everyone working on the project, that it inspired career decisions and a love of rare books in many of those volunteers. It was while at UCL, close to his 65th birthday, that he was diagnosed with the cancer from which he died in December 2016.

Fred Bearman was both a naturally gifted public speaker and a superb teacher, having the ability to turn any apparently stuffy or arcane field into an exciting and accessible subject, whether lecturing for the National Archives in Washington, USA and the Bibliographical Society of the UK, or teaching early-profession conservation students at West Dean College and guiding undergraduates at UCL in their first ever encounter with a medieval book. His own outstanding achievements, combined with his refusal to be restricted by his dyslexia and partial deafness, inspired confidence in students and colleagues dealing with their own adversities.

Sometimes Fred compared teaching to performing. Indeed, in his youth he showed a remarkable ability as a performer of early dance, ranging with ease from the medieval period to the eighteenth century. As a young man he worked as a dancer for Nonesuch Dance Group and the Renaissance Dance Company, both associated with the early-music revival of the 1970s, and helped run workshops in early dance for schoolchildren in some of the most challenging inner-city schools under the auspices of the former Inner London Education Authority.

His skill in linking the historical context in which books were made with a professional’s understanding of their physical construction, together with having the courage to ask deceptively simple but entirely new questions, led to ground-breaking publications such as those on girdle books and chemise bindings, and on laced overbands and stationery bindings. He had a keen sense of wit, but also a remarkably down-to-earth ability to hit the proverbial scholarly nail on the head.

Fred had a great love of Classical music, stretching from Bach to the Romantics and beyond, with a particular passion for Beethoven. He was a keen gastronome, an ardent museum-goer, and a staunch socialist and trade unionist. His warmth and generosity in encouraging those around him to fulfil their own talents, while reminding them to enjoy every minute of it, will be sorely missed. He is survived by his partner of four decades, the modern-art historian and preeminent scholar of Abstract Expressionism, Dr. David Anfam.

Close

Close