Social Media Rants from the Past

By Erika Delbecque, on 5 July 2019

This blog post was written by Patricia Jager, an MA student at the Institute of Archaeology who is currently volunteering with UCL Special Collections. She is compiling a list of our 1914-18 collection, with the aim of making this uncatalogued material available for teaching, events and research.

Today we have become used to annoyed social media posts popping up on our feeds from friends, family and random people we once met on holiday. They cover a wide range of political issues and pet peeves that can be funny, inspiring or infuriating depending on which side of the issue you are on. From the perspective of future archaeologists and cultural heritage managers, the internet offers an unprecedented window into current issues on a global level.

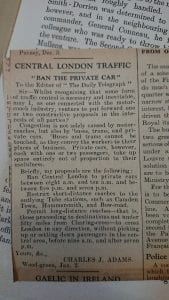

However, venting one’s frustration on media platforms does not seem to be an entirely contemporary concept. While listing ‘The British campaign in France and Flanders 1914’ by Arthur Conan Doyle from the 1914-18 collection at UCL Special Collections, I stumbled across a newspaper cut-out from January 5th, 1931 that one of the previous owners must have left behind. While this excerpt was doubtlessly chosen for the main article, it accidentally helped some letters to the editor survive.

However, venting one’s frustration on media platforms does not seem to be an entirely contemporary concept. While listing ‘The British campaign in France and Flanders 1914’ by Arthur Conan Doyle from the 1914-18 collection at UCL Special Collections, I stumbled across a newspaper cut-out from January 5th, 1931 that one of the previous owners must have left behind. While this excerpt was doubtlessly chosen for the main article, it accidentally helped some letters to the editor survive.

They caught my eye because one of them regarded Central London traffic, which apparently was already horrible more than 80 years ago. When comparing the original letter to most of the digital commentary I encounter on social media every day, I was struck by its polite tone that is definitely a thing of the past. If one would use such a comparison to infer the difference between past and current populations, one would believe that our manners had progressively deteriorated over time.

The actual difference between past and modern, however, might be the result of biases. The internet allows us all to act simultaneously as authors and publishers of our written work. Letters to the editor, on the other hand, are selected by the newspaper agency and must abide by certain standards. Anyone, no matter their background, social status or level of education can leave commentary on social media platforms meaning a true variety of opinions are represented and available to future historians. However, how all this data could be archived, catalogued and studied is a question that cannot yet be fully answered, and I doubt that most of us consider what researchers might think about the opinions we share online in a hundred years’ time.

Probably, Charles J. Adams, the author of the letter I found by sheer accident would never have imagined his work published in a completely new medium nearly a hundred years later, especially because it seems like no politician ever read or implemented his sensible proposal. Consequently, letters to the editor and social media rants have at least one thing in common: they are being perpetually ignored by those in charge.

Close

Close