Tattoos That Repel Venomous Creatures! The Tragic Tale of Prince Giolo

By Gemma Angel, on 27 May 2013

by Gemma Angel

by Gemma Angel

The tattooed body has been an object of spectacle and a source of fascination in Europe for at least 4 hundred years. Tattooed natives captured by European explorers were transported to Europe and put on display as curiosities or ‘sights’ from as early as the middle of the 16th century. In 1566, a tattooed Inuit woman and her child were kidnapped by French sailors and put on display in a tavern in Antwerp, The Netherlands. 10 years later, the sometime pirate and seaman Martin Frobisher returned to England from his voyage to Baffin Island in northeastern Canada with a native man whom he had abducted; this unfortunate individual caused such a stir in London, that Frobisher returned from his second voyage to the region with 3 more Inuit captives, who drew equally fascinated crowds when he landed in Bristol. Sadly, all 3 of his human cargo died shortly after their arrival on British shores, succumbing to common European illnesses against which they had no natural immunity.

A similar fate befell the Miangas islander named Jeoly, who became popularly known as ‘Prince Giolo’ when he arrived in England in 1691. Perhaps the most famous of all the tattooed ‘curiosities’ exhibited in Britain, Jeoly was purchased as a slave by the buccaneer-adventurer William Dampier in Mindanao, the Philippines, in 1690. Having failed in his ambitions to discover unexploited spice and gold wealth in the Spice Islands, Dampier returned to England broke, with only his diaries and his ‘Painted Prince’ to show for travels. On his arrival home, Dampier sold Jeoly on to business interests, and later published his journals under the title A New Voyage Around the World, in 1697. In these diaries, Dampier describes Jeoly’s elaborate tattoos in some detail:

He was painted all down the Breast, between his Shoulders behind; on his Thighs (mostly) before; and the Form of several broad Rings, or Bracelets around his Arms and Legs. I cannot liken the Drawings to any Figure of Animals, or the like; but they were very curious, full of great variety of Lines, Flourishes, Chequered-Work, &c. keeping a very graceful Proportion, and appearing very artificial, even to Wonder, especially that upon and between his Shoulder-blades […] I understood that the Painting was done in the same manner, as the Jerusalem Cross is made in Mens Arms, by pricking the Skin, and rubbing in a Pigment. [1]

Playbill advertising ‘Prince Giolo’ in London, 1692.

Etching by John Savage.

Image courtesy of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Australia.

Jeoly was put on display ‘as a sight’ at the Blue Boar’s Head Inn in Fleet Street in June 1692. A number of copies of the playbill advertising his public appearances survive (pictured above). The original advertisement includes a detailed etching of Jeoly by John Savage, showing the tattoos over the front of his body, arms and legs, which resemble traditional Micronesian tattoos of the Caroline and Palau Islands. [2] As well as this striking image, a somewhat embellished story of his life was printed beneath the illustration. Interestingly, this accompanying text ascribes potent protective and healing powers to Jeoly’s tattoos, claiming that his people believed them to be a defense against ‘venomous creatures’:

The Paint it self is so durable, that nothing can wash it off, or deface the beauty of it: It is prepared from the Juice of a certain Herb or Plant, peculiar to that Country, which they esteem infallible to preserve humane Bodies from the deadly poison or hurt of any venomous Creatures whatsoever.

Whilst tattooing was considered to possess magical, protective and medicinal properties in many cultures, it is more than likely that the stories claiming that Jeoly’s tattoos repelled venomous creatures were dreamed up by his exhibitors, rather than having any genuine basis in his own native belief system. Dampier himself remarked upon the ‘Romantick stories’ which circulated in England about Jeoly’s origins, openly ridiculing the marketing campaign:

In the little printed Relation that was made of him when he was shown for a Sight in England, there was a romantick Story of a beautiful Sister of his a Slave with them at Mindanao; and of the Sultan’s falling in Love with her; but they were Stories indeed. They reported also that this Paint was of such Virtue, that Serpents, and venomous Creatures would flee from him, for which reason, I suppose, they represented so many Serpents scampering about in the printed Picture that was made of him. But I never knew of any Paint of such Virtue: and as for Jeoly, I have seen him as much afraid of Snakes, Scorpions, or Centapees, as my self. [3]

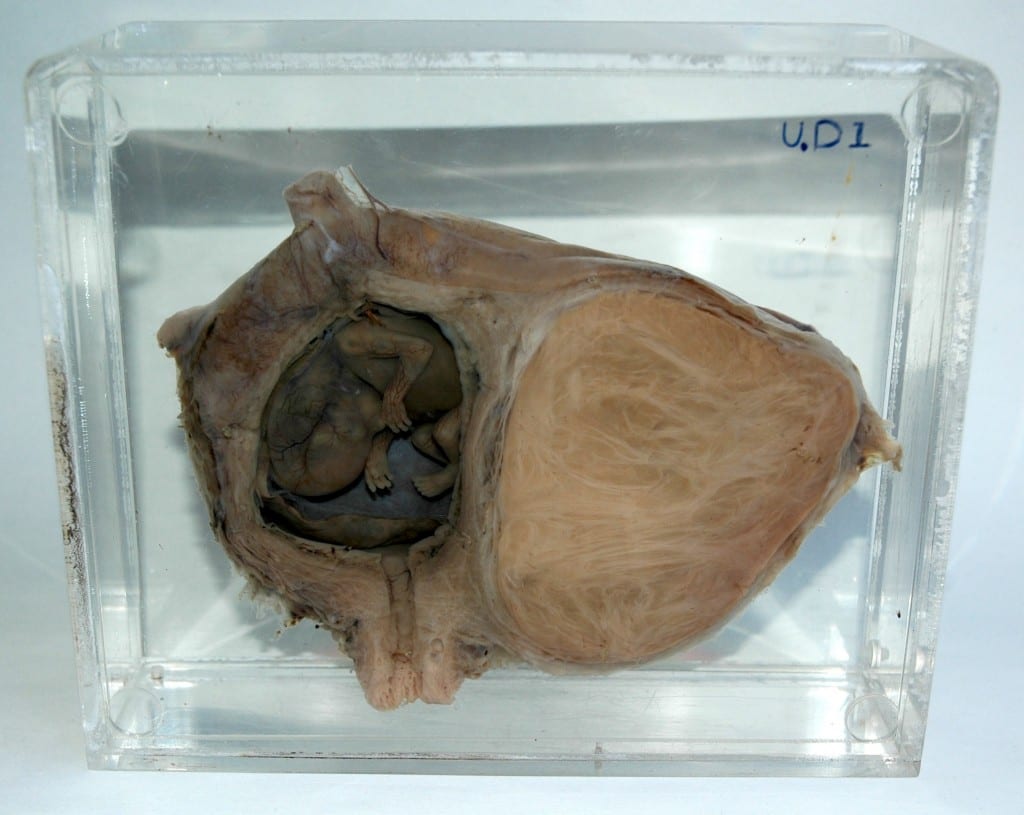

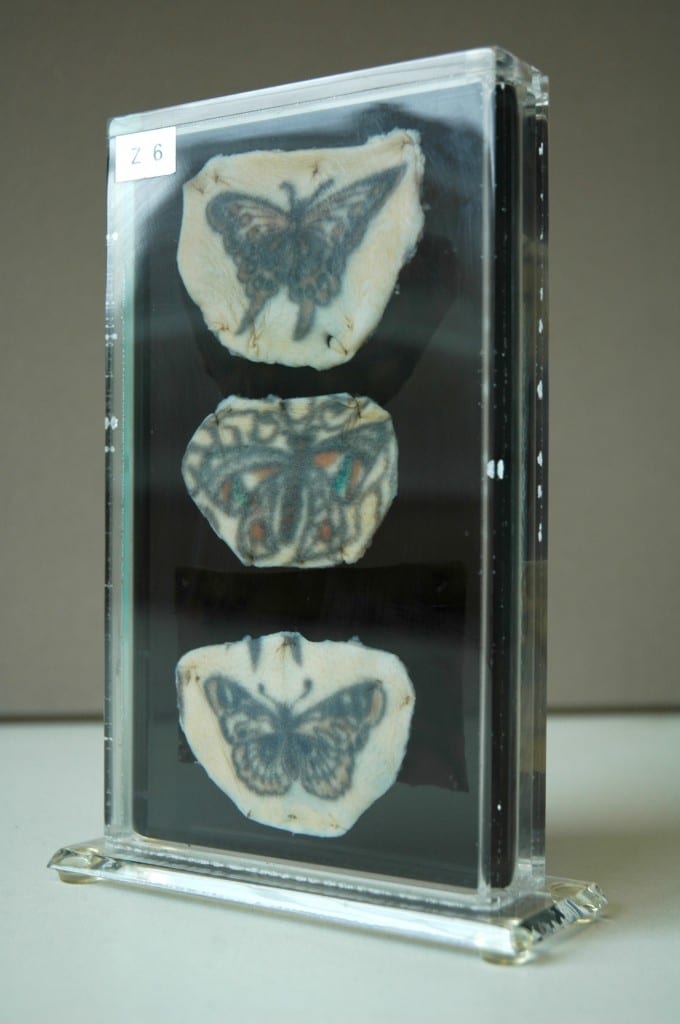

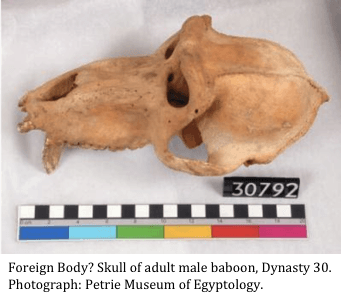

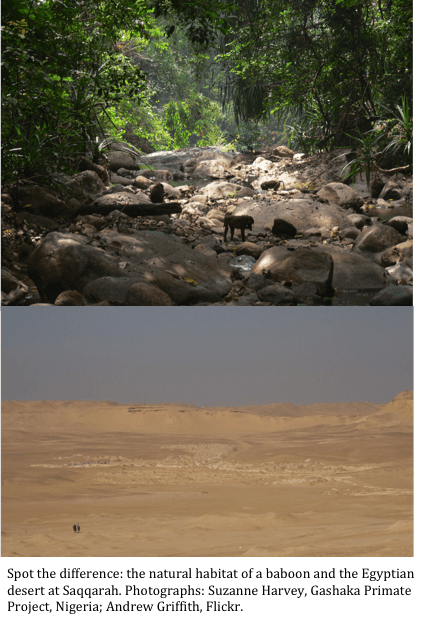

In the lower foreground of the illustration, a variety of reptiles and scorpions can be seen fleeing from Jeoly’s feet, his tattoos apparently acting as some kind of aposematic deterrent. Tragically however, Jeoly’s tattoos could not protect him from the foreign infections that he was exposed to in England; he died of smallpox in Oxford sometime in 1693. Although his grave is not marked, and his name does not appear in the Parish register, Jeoly is thought to be buried in St Ebbe’s Churchyard. After his death, a fragment of his tattooed skin was removed and preserved for the Anatomy School collections at Oxford University by the surgeon Theophilius Poynter. This skin fragment was recorded in a list of ‘Anatomical Rarities’ in the Appendix of John Pointer’s 4 volume catalogue for his Musaeum Pointerianum, the cabinet of curiosities he left to St. John’s College Oxford in 1740. [4] Although the skin did not survive, having been lost by the early 20th century, this appears to be the first documented instance of the collection and preservation of tattooed human skin as an anatomical curiosity in England.

Jeoly’s tragic story of enslavement, forced re-location to Europe, public exhibition for profit, fatal illness, and the preservation of his tattooed skin for display as an anatomical rarity, speaks of the foreign body on multiple levels. From the 16th century onwards, the tattooed body of the native became a powerful symbol of foreignness, that could reliably draw curious European crowds and turn a profit for unscrupulous entrepreneurs; but the consequences for displaced foreigners like Frobisher’s Inuits and Dampier’s ‘Painted Prince’ were grave indeed. Exposed to invisible and deadly foreign bodies such as measles and smallpox, they died far from home, unable to fight off common European illnesses against which they had no natural defences.

References:

[1] William Dampier, A New Voyage Around the World, ed. N. M. Penzer (London: Adam & Charles Black), 1937, p. 344.

[2] See Tricia Allen, “European Explorers and Marquesan Tattooing: The Wildest Island Style” in D.E. Hardy (ed) Tattootime Volume V: Art from the Heart, (1991) pp. 86-101; also Kotondo Hasebe, “The Tattooing of the Western Micronesians” in The Journal of the Anthropological Society of Tokyo Vol. XLIII No.s 483-494 (1928), pp. 129-152 (in Japanese).

[3] Dampier, A New Voyage Around the World, p.346.

[4] Geraldine Barnes “Curiosity, Wonder and William Dampier’s Painted Prince“, Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2006), p. 32 & 43.

[analytics-counter]

Close

Close