By Hannah Wills

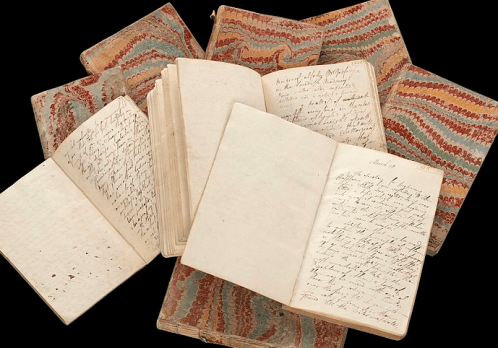

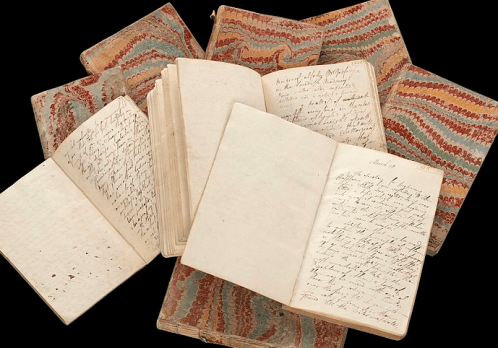

Earlier this summer, I gave a talk with some of the other engagers at our ‘Materials & Objects’ event at the UCL Art Museum. In preparing for the event, we were all challenged to think about the objects, materials, and physical ‘stuff’ that we work with on a daily basis. As I’ve written about before, my research focuses on the notebooks and diaries of a late eighteenth-century physician and natural philosopher, Charles Blagden (1748-1820), who served as secretary to the Royal Society. One of the things I’m interested in is how Blagden used his notebooks and diaries to keep track of his day-to-day activities, as well as the business of one of London’s major learned societies. Record keeping and note taking was a central part of Blagden’s life, and it’s owing to his impressive record keeping habit that there’s one material I handle in my research more than any other: eighteenth-century paper.

A selection of Blagden’s many notebooks, held at the Wellcome Library. (Image credit: Charles Blagden, L0068242 Lectures on chemistry, Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images, MSS 1219 – MSS1227. CC BY 4.0)

When I began preparing my talk for ‘Materials & Objects’, I started to think about how I might bring paper, a relatively mundane material, to life. My initial reading on the craft of papermaking told me that despite it being a 2000-year old process, making paper by hand has changed relatively little between then and now.[i] Out of curiosity, I decided to do an experiment, and to see if I could replicate some of the processes of eighteenth-century papermaking at home, in my kitchen.

The first stage in the papermaking process is to select the material from which the paper is going to be made. In the eighteenth century, this would typically have been cotton and linen rags. Towards the end of the century, shortages of rags, in part caused by an increased use of paper for printing, meant that makers began to experiment with other materials. In 1801, the very first book printed on recycled paper was published in London—that is, paper that had been printed on once before already.[ii]

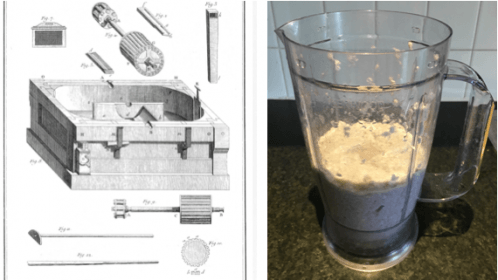

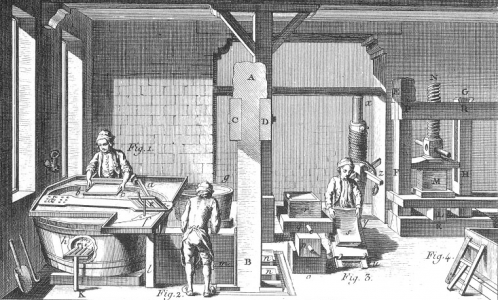

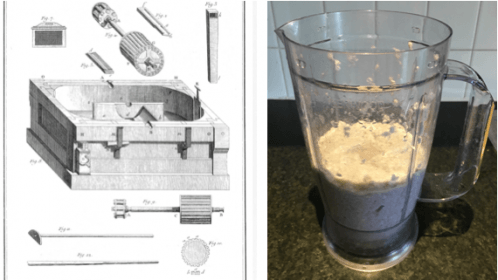

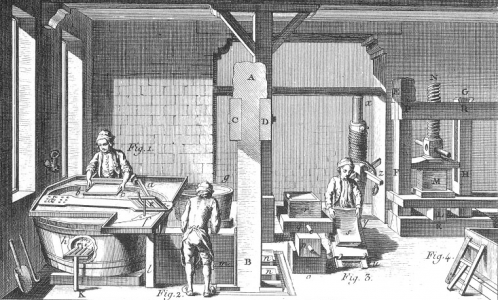

Having selected the material, the next step is to break it down, making it into a pulp. When papermaking was first introduced in Europe in the twelfth century, rags were wetted, pressed into balls, and then left to ferment. After this, the rags were macerated in large water-powered stamping mills.[iii] In the eighteenth century, a beating engine, or a Hollander, was used to tear up the material, creating a wet pulp by circulating rags around a large tub with a cylinder fitted with cutting bars (see below).[iv] For my purposes, I found a kitchen blender worked well to break up scraps of used paper from my recycling bin at home, ready to make into new blank sheets.

(Left) Eighteenth-century illustration of a beating engine, from Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 5, Paris, 1767. (Right) A kitchen blender achieves roughly the same effect, breaking up old used paper soaked in water to create a pulp. (Image credits: Left “Papermaking. Plate VIII” The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Abigail Wendler Bainbridge. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2013. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Right Hannah Wills)

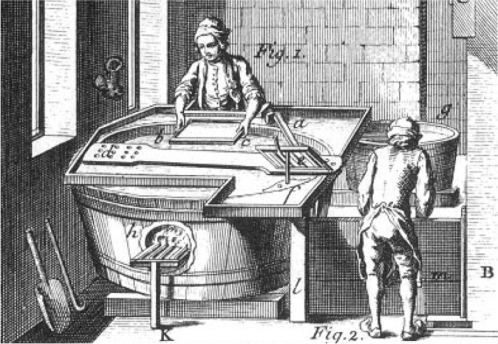

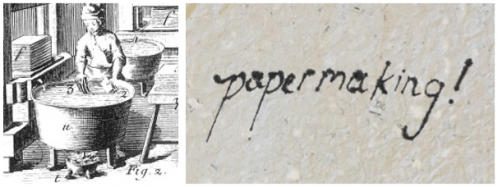

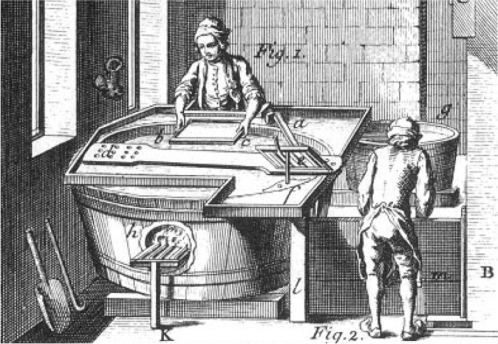

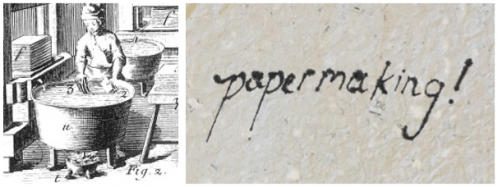

Having been broken down, the liquid pulp mixture is then transferred to a container. In the eighteenth century, someone known as the ‘vatman’ would have stood over this container and dipped a mould into the solution at a near-perpendicular angle. Turning the mould face upwards in the solution before lifting it out horizontally, the vatman would have pulled out the mould to find an even covering of macerated fibres assembled across its surface. It is these fibres that would later form the finished sheet of paper.[v]

An eighteenth-century vatman dipping the mould into the vat. (Image credit: Detail “Papermaking. Plate X” The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The moulds used in papermaking determine several features of the finished sheets of paper, including shape, texture and appearance. The type of mould first used in European papermaking was known as a ‘laid’ mould. This mould typically featured wires laced horizontally into vertical wooden ribs, meaning that when the mould was pulled out of the vat, the pulp would lie heavier on either size of the wooden ribs, giving vertical dark patches and the characteristic markings of ‘laid’ paper.[vi]

A laid mould, with vertical wooden ribs and horizontal wires. A design and marker’s name are visible sewn into the mould, and will leave what is known as the ‘watermark’ on individual sheets of paper. (Image credit: Laid mold and deckle, Denmark – Robert C. Williams Paper Museum, CC0 1.0)

Characteristic ‘link and chain’ pattern found on laid paper, left by the ribs and wires. This piece is a modern imitation of antique laid paper. (Image credit: Hannah Wills)

In mid-eighteenth century Britain, a new type of mould became widely used, developed by the Whatman papermakers based in Kent. This mould was known as a ‘wove’ mould, and had a much smoother surface, consisting of a fine brass screening that was woven like cloth. These moulds imparted a more uniform and fabric-like texture to individual sheets.[vii]

A wove mould, featuring two large watermark designs. Between the watermarks the smooth surface of the woven screening is visible, which leaves the paper with a fabric-like textured appearance, without the prominent horizontal and vertical lines of laid paper. (Image credit: Wove mould made by J. Brewer, London, England – Robert C. Williams Paper Museum, CC0 1.0)

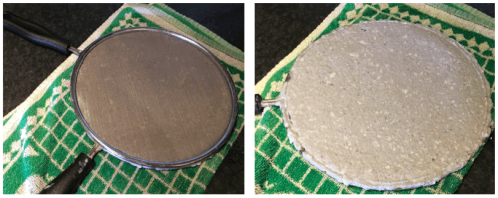

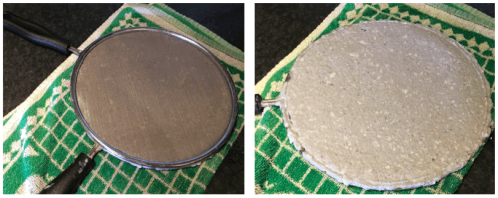

For my own papermaking, I chose to dip a piece of fine sieve-like material into my makeshift vat, aiming to replicate partially the texture and appearance of a ‘wove’ mould. The implement I chose for this was a small kitchen pan splatter guard, made up of fine mesh that when pulled out of the vat would hold a layer of fibres on its surface.

My chosen mould, a kitchen pan splatter guard, made from fine sieve-like material. (Image credit: Hannah Wills)

Dipping the mould into the vat and removing slowly, fibres are left on the surface of the mould. (Image credit: Hannah Wills)

After the mould was pulled from the vat, the eighteenth-century vatman would pass it on to a coucher who would remove the sheet from the mould, before pressing it between felts to remove the water.[viii]

On the left, the vatman pulls the mould from the vat, before passing it to the coucher on the right hand side of the image, who removes the sheet from the mould before pressing a number of sheets at the same time in a large press. (Image credit: “Papermaking. Plate X” The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

In order to remove my sheet of paper from the mould, I placed another sieve-material implement over the top of the fibres and pressed down with a sponge. With a tea towel placed underneath, this worked to remove much of the water without the need for a proper press. Pulling the top piece of sieve away from the bottom, I was left with a drier surface of fibres, which could be carefully lifted off the mould, and set aside to dry.

(Left) Pressing the sheet of fibres between two splatter guards. (Right) After the top guard is removed, the pressed sheet of paper is revealed. The circular shape is due to the shape of the mould. (Image credits: Both Hannah Wills)

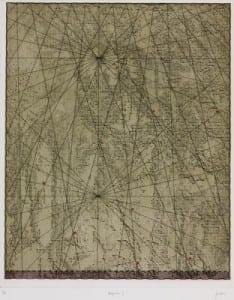

At this point in the eighteenth-century process, sheets were ‘sized’—dipped into a gelatinous substance made from animal hides that made the sheet stronger and water resistant.[ix] After my sheets had been left to one side to dry for a few hours, I decided to experiment by writing on them. I had not applied size to any of my sheets, so found that when I wrote on them the ink spread out, giving a sort of blotting paper effect.

(Left) After pressing, the sheets are dipped into large tub containing size. This step is important if the paper is to have a slightly waterproof quality that enables it to be written on without the ink spreading. (Right) Writing with ink on untreated sheets results in the ink spreading out across the paper. (Image credits: Left “Papermaking. Plate XI” The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Right Hannah Wills)

After having size applied, sheets in an eighteenth-century papermill would have undergone a number of finishing stages. These included polishing and surfacing, processes that gave the paper a more uniform appearance.[x] With my own sheets of paper, I found passing a warm iron over the surface achieved a similar effect, removing some of the creases and wrinkles that had appeared during drying.

My finished sheet of paper, trimmed down into a small square ready for use. (Image credit: Hannah Wills)

It is after these final finishing and drying processes that sheets of paper are ready to be packaged up and sent to the stationer’s.

Replicating historic crafts and processes is not new within the discipline of history. One of my favourite examples is a paper that was published in 1995, in which the historian Heinz Otto Sibum recreated the experiments of the scientist James Prescott Joule (1818-1889) in determining the mechanical equivalent of heat. By trying to recreate the experiment from Joule’s notes, Sibum revealed that Joule made frequent use of the bodily skills he developed while working in the brewing industry, such as the ability to measure temperatures remarkably accurately by using only his elbow.[xi] Often, attempting to replicate an experiment or craft will reveal just how much it relies upon implicit bodily skills, or tacit knowledge, the kinds of ‘knacks’ that are not written down but are simply known to those who perform an activity regularly.

In attempting to replicate the craft of eighteenth-century papermaking, I really only approximated the process, making substitutions for equipment and improvising a number of techniques, particularly when it came to removing my delicate wet sheets of paper from the mould. I think the biggest lesson I learnt was to have a greater appreciation of the material, and just how many skills and processes went into crafting each sheet of paper in the eighteenth century. Characteristics of individual sheets such as colour, texture and markings had not caught my attention in the archives previously, but I now find them fascinating for what they can reveal about the nature of the fibres used, the construction of the paper mould, and the processes followed by each individual papermaker.

References:

[i] Dard Hunter, Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft (New York: Dover, 1978), 178.

[ii] Ibid., 309-33.

[iii] Ibid., 153-55.

[iv] Theresa Fairbanks and Scott Wilcox, Papermaking and the Art of Watercolour in Eighteenth-Century Britain: Paul Sandby and the Whatman Paper Mills (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art in association with Yale University Press, 2006), 68.

[v] Hunter, Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, 177.

[vi] Ibid., 114-23.

[vii] Ibid., 125-27. See also Fairbanks and Wilcox, Papermaking and the Art of Watercolour in Eighteenth-Century Britain: Paul Sandby and the Whatman Paper Mills.

[viii] Papermaking and the Art of Watercolour in Eighteenth-Century Britain: Paul Sandby and the Whatman Paper Mills, 71.

[ix] Hunter, Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, 194.

[x] Ibid., 196-99.

[xi] Heinz Otto Sibum, “Reworking the Mechanical Value of Heat,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 26, no. 1 (1995): 73-106.

Close

Close