By Stacy Hackner

By Stacy Hackner

Some respected individuals (supervisors, mentors, parents) have advised me to not get distracted by the primrose paths that crop up during a PhD. These primrose paths are always deliciously exciting, offering opportunities to study wonderful new topics that one can justify as marginally related to one’s thesis and therefore potentially of use. Of all the primrose paths I’ve followed, I never expected the most relevant one to be about astronauts.

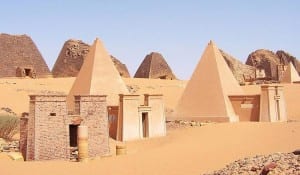

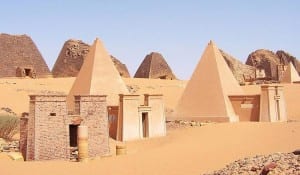

Sudanese pyramids. (Wikimedia commons.)

My thesis explores ancient Nubia, the region that is now northern Sudan, from roughly 3000 years ago to medieval times. Unlike their contemporaries, the Egyptians, the Nubians didn’t have a system of writing until the Meroitic period (300 BCE-400 CE), a time of Egyptianizing influence. They built small pyramids and imported Egyptian goods, attesting to the influence of their famous northern neighbors. In the absence of writing (and even in the presence of texts, as humans tend to play with the truth), archaeologists try to build a picture of the ancient society using physical evidence, including human remains. Fortunately, the dry climate and sandy soil usually result in excellent bone preservation, allowing me to identify differences in bone shape. But wait – let me back up a little.

We aren’t entirely sure how bone works. There are two types of cell responsible for bone maintenance – osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Osteoblasts build bone, and osteoclasts take it away. The body is highly responsive to changes in activity, and bone is constantly updating itself accordingly. The general principle is that your body thinks what’s happening now will happen forever. Think about when you’re running a race: it’s hard to start because your body’s been used to standing still and needs some time to amp up your heart rate and muscle contractions. When you finish the race, your heart keeps pounding for a minute or two because it hasn’t quite got the signal to stop running yet. Bone works in a similar way. In response to physical stress, bone will accumulate more osteoblasts to strengthen itself. Each step makes tiny microfractures, which tells the bone “Come on, I’m breakin’ here! Give me more strength!” and the osteoblasts pile on. In the absence of activity – during periods of prolonged sitting or lying down – the osteoclasts come in to take away unnecessary bone. “You’re not using this one, right? Then we can send the calcium somewhere else.” The thing is, scientists don’t know all the signals involved in this process. We know what happens, but not the channels of communication. I like to imagine bone cells having little conversations with each other, but clearly it’s all on a neurochemical level we haven’t yet discovered.

The concept of bone building in necessary areas is keenly presented in studies of elite athletes. In a study by Haapsalo et al (1998) of young female tennis players, the players gained significant bone mineral content in the bones of their dominant (forehand and serving) arm. When the authors looked at a control sample (girls who did not play tennis), there was minimal or no difference between their arms; there was also minimal difference between the nondominant arms of the tennis players and the controls.

Another study, by Shaw & Stock (2009), examined differences between university athletes who competed in either hockey or long-distance running. They found significant differences in the actual shape of the tibia (shin bone) due to the physical stress of these activities. The tibias of the long-distance runners were more elongated front to back while the tibias of the hockey players were more even side-to-side, showing a distinct difference in the direction of activity in these sports. Clearly, osteoclasts were being sent to the bone locations these athletes needed them most: for runners, the front, and for hockey players, the sides. It is important to point out that many of the studies investigating activity and bone growth look at adolescents, since their bones develop until the end of puberty. After that, it seems to take a lot more effort to alter bone shape and density.

Her bones are losing mineral content by the minute! (Wikimedia commons.)

And what about the other side of the cycle? The osteoclasts? That’s where the astronauts (and cosmonauts) come in. The constant pounding of our feet against the floor keeps our bones as strong and dense as they need to be for everyday use. In zero gravity, though, there’s no pounding, just the occasional soft push off the wall of the space station. The osteoblasts don’t have any stress to react to, and the osteoclasts assume the extra bone is useless, so it starts to be resorbed. It helps that astronauts are some of the most-studied individuals on our planet (and definitely the most studied off the planet!). During spaceflight, urine calcium output is found to increase, indicating that bone is being sapped of minerals, and post-spaceflight bone scans reveal a condition called “spaceflight osteoporosis”, similar to the osteoporosis experienced on earth – but the bone density is only lost from the legs, feet, and hips, all weight-bearing regions, including an 8% loss in four months (compared to 1% loss per year for earth-bound sufferers of osteoporosis). The upper body and head generally remain unaffected (unless one of the astronauts was a tennis player, of course). One study found that after a “long-duration” spaceflight of 4-6 months, it took up to three years for astronauts to recover the bone density they’d lost in space (Sibonga et al, 2007). It makes one really appreciate gravity.

So how do I apply this to ancient populations? The data from astronauts indicates that most of the density lost is from trabecular bone, from the internal core, rather than from the outside. This means that even if ancient bones have lost density due to age, either before death or after burial, it’s likely to have happened from the inside out and thus the external shape should remain intact. This gives me more confidence in figuring out what kinds of activities they performed during adolescence, which in most cultures was when young people started to take up adult cultural roles. I hope to compare the shape of the bones of Nubians to those of athletes and to other populations whose activities are known in order to draw a better picture of their society.

Sources

For an amusing (but factual) look at the craziness that is astronaut and cosmonaut research, check out Mary Roach’s “Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void” (Norton & Co, 2010).

Haapasalo, H, P Kannus, H Sievänen, M Pasanen, K Uusi-Rasi, A Heinonen, P Oja, and I Vuori. 1998. Effect of long-term unilateral activity on bone mineral density of female junior tennis players. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 13/2, 310-319.

Shaw, CN and JT Stock. 2009. Intensity, Repetitiveness, and Directionality of Habitual Adolescent Mobility Patterns Influence the Tibial Diaphysis Morphology of Athletes. AJPA 140, 149-159.

Sibonga, JD, HJ Evans, HG Sung, ER Spector, TF Lang, VS Oganov, AV Baulkin, LC Shackelford, and AD LeBlanc. 2007. Recovery of spaceflight-induced bone loss: bone mineral density after long-duration missions as fitted with an exponential function. Bone 41, 973-978.

Close

Close