Movement Taster – Blockages in the system: health research in postwar Britain

By Kevin Guyan, on 19 May 2014

By Kevin Guyan and Ruth Blackburn

This taster is from a larger presentation, Blockages in the system: health research in postwar Britain, which forms part of the Student Engagers’ Movement event taking place at UCL on Friday 23 May. What follows is a sample of the interdisciplinary work by PhD students Kevin Guyan, Department of History, and Ruth Blackburn, Department of Primary Care and Population Health, linking their interests in 20th century British history and health sciences. Movement will also relate these ideas to objects from UCL Collections as well as giving attendees an audiovisual experience of travelling on a London Routemaster bus.

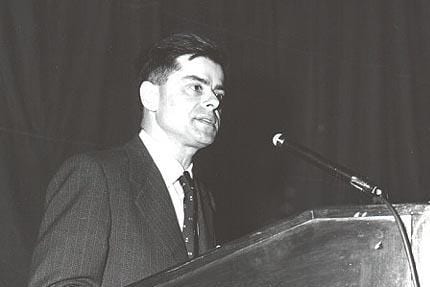

The links between good physical health and exercise have only relatively recently been established. In the postwar decades there was particular interest in investigating heart disease: an increasingly common ailment with causes that were poorly understood at the time. Jerry Morris (1910-2009), Emeritus Professor of Public Health at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and commonly referred to as the father of exercise epidemiology, was the first to establish proof that the frequency and severity of heart disease was reduced among workers who did more active jobs.

He made this discovery in the late 1940s by conducting an innovative and efficient ‘experiment’ that studied the behaviour and indicators of physical health in several thousand London Transport employees; particularly focusing on health differences between bus drivers and conductors. The selection of the two study groups was critical for the success of the experiment. This is because the bus drivers and conductors were very similar groups of people in most respects (e.g. age, socio-economic status and diet) but differed in terms of the amount of physical activity that was undertaken whilst at work.

By studying differences in the rates of cardiovascular disease between these two groups the ‘bus men study’ showed that the additional physical activity that bus conductors undertook whilst at work was associated with a 50 per cent reduction in heart disease. This finding was the first real evidence to demonstrate that being more active brought substantial health benefits and highlighted the importance of exercise as a public health intervention.

It is now time to position Jerry Morris’s study within the wider context of postwar London, showing that his research on the health of London transport workers was a product of its time and is an interesting example of broader changes in how ‘experts’ were understanding and explaining human action and behaviour.

The decades following the Second World War experienced a widening of ‘expert knowledge’, particularly within fields linked to the physical and social health and well-being of citizens. The esteem of qualities associated with experts also underwent a shift: moving from the predominance of highbrow cultures (for example, the humanities) to also include masters of science, skill and technology. This period was witness to the rise of the scientific and technical expert.

The belief that experts were striving for a ‘New Jerusalem’, a utopian ideal removed from the realities of postwar austerity, often distract discussions of British planning. However, there was undoubtedly a political dimension to these projects, reflecting the politics of the Left, Fabianism and the Labour Party. It is not coincidental that Morris was a Socialist and championed the need for state intervention to improve the welfare of the population throughout his life’s research. In his work, the line between science and politics is often blurred – expressing the view that positivist forms of science work in tandem with socialist principles. In this political vision of a New Britain, the rational and modern nation would require the successful management of health and disease. Morris and his expert knowledge of epidemiology would therefore position him as a central figure in this imagined future.

This interest in the political led to what is arguably the most interesting development in his work: his definition of the individual. Morris did not focus on moral deviancy or communities positioned on the edge of society; nor, in his ‘bus men study’, was his primary focus the influences of class or social situation. Instead, his chief research interests were individual actions and ways of living, removed from their social and economic contexts.

By moving the focus of one’s likelihood to encounter disease away from social class or community and instead considering the activities that individuals perform, although throughout his life’s work Morris was deeply interested in how socioeconomic factors affect the activities people perform, the ‘bus men study’ differed from the approach of scientists before him. Importantly, the fluid nature of modern life was also acknowledged and the need to view subjects as ‘changing people’ operating in changing social environments. As experts grew more willing to challenge the influences of social class and instead consider the complex effects of social and biological relations, ‘ways of living’ emerged as a primary factor in the study of health and disease. The offshoot of this finding was groundbreaking: a call for the reform of everyday lifestyles. With this conclusion, Morris’s ‘bus men study’ should not only be viewed as a key text in epidemiology but also as part of a wider shift in 20th century Britain over the role of scientific expertise and definitions of the individual.

Close

Close