It will not be lost upon anybody that visits the Grant Museum of Zoology or the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology at UCL that these are places of death. Both are a kind of necropolis, containing preserved remains. The remains of the biologically dead, in the former; in the latter, the preserved remains – biological and cultural – of the long deceased people of ancient North African civilisations, many of which are themselves vessels or tokens designed to smooth the passage of the dead to another, immaterial realm.

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

The morbid nature of these museums and the objects they house would not be lost on the 20th Century German philosopher Theodor Adorno. The word “museum” derives from the Greek mouseion, meaning “seat of the muses”, a fact which emphasises the supposedly inspirational nature of these cultural institutions. But for Adorno, the creativity-inspiring significance of the museum had in contemporary Western society been eclipsed by its material and cultural function. In his essay “Valéry Proust Museum”, Adorno dwells upon the macabre nature of the museum, and the art gallery. The German term museal (“museum-like), he tells us, is a suggestively pejorative one used to describe the character of certain artefacts: objects to which the observer or museum-goer ‘no longer has a vital relationship and which are in the process of dying’. We come close to this in the English language when, by saying something or someone “belongs in a museum”, we describe people, technologies, institutions, or ideas that have far exceeded their sell-by date and have become decrepit.

Adorno’s observation is literally true in many cases. Walk through the atria of the Science Museum in South Kensington and you will see installed behind glass a host of superannuated but undeniably contemporary artefacts – Bakelite telephones, Atari computers, horsehair toothbrushes, and so forth. We are being told: by virtue of being useless, these objects are displayed in this museum. Or perhaps: by installing these objects in a museum, these objects should now be considered obsolete (even if they are still technically useful).

The same could be said about art. Once installed in a museum or gallery, a painting, print, or sculpture becomes a commodity whose value is defined primarily by its capacity to create profit – for the museum, the artist, the collector, or the dealer. The life of that artwork – its social, spiritual, philosophical, aesthetic value outside that of commerce or “cultural capital” – has been destroyed by the same process of display operative in the Science Museum, which by selecting and displaying objects consigns them to the grave. Art is on display because it is monetarily valuable; being in a museum ascribes monetary value to art. Forget the muses, Adorno says: ‘Museum and mausoleum are connected by more than phonetic association. Museums are like the family sepulchres of works of art. They testify to the neutralisation of culture.’

This conception of the museum as mausoleum can illuminate two apparently divergent kinds of museum display, both of which can be understood to drain the life from the objects they seek to exhibit. First, any attempt to place works of art in so-called “authentic”, historical settings is not only a shabby form of nostalgia. Such a move, in a desperate attempt to claw back an irretrievable cultural tradition, reduces to a form of historical citation the artwork it seeks to celebrate. This can lead only to melancholy. For such a purely referential and reverential effort to recuperate the past will always fail, leaving us to lament uselessly the passing of historical time. We resign ourselves to the fact that the historical context that gave life to the artwork is lost to us; and that, therefore, the artwork is itself dead.

The seemingly contrasting practice of deliberately wrenching art from its historical and aesthetic context – such as in the contemporary fashion for “white cube” galleries – can be understood as equally unsatisfactory and inauthentic, since this form of exhibition strips art of its history altogether. Historical nostalgia might at lead us, at least, to a despairing and therefore critical conception of the impossibility of grasping the life of art in undistorted historical context. Decontextualisation wears inauthenticity as a badge of honour. The false trappings of tradition and the over-serious officiousness of the desire for authenticity of which it is symptomatic squeezes the life from art entirely. Willing dilettantism denies us the opportunity of understanding the historical nature of art — however incomplete that understanding might be.

This double bind is a useful way of understanding the objects we see in the Grant Museum in UCL. Adorno’s analysis in “Valery Proust Museum” is aimed at art and art museums primarily. But reading in this way, for example, the literally dead animals in a museum of zoology can illuminate how, through being displayed, they have become museal. How does one display a dead animal? In a mock-up of its original habitat – a tawdry and macabre mirror of the attempt to display art in “authentic” context? Or should we simply display it in a glass box, stripped of context – continuing the violent logic of ecological, geographical displacement that resulted in that animal’s death and preservation?

A taxidermic preservation of an African Elephant Shrew, The Grant Museum (Z2789)

The former, at least, by offering us a glimpse into the original habitat of a species might offer us an unintended critique of how in British museums of zoology many of the species on display are relics of a violent colonial past: animals whose death and passage to Britain was made possible by an imperial infrastructure of scientists, surgeons, and interested amateurs, scattered across British dominions. However, even the act of preservation itself is a false kind of de-contextualisation. While the skeletons, preserved, and stuffed species that line the walls of the Grant Museum were intended first for scientific education and research, as a spectacle they take on a distinctly melancholy aspect. This is especially true for the display of extinct species; thylacine parts, dodo bones, a quagga skeleton: these are embodiments of a desire to preserve what is dead, to recuperate – through entirely artificial means – what is irretrievably lost.

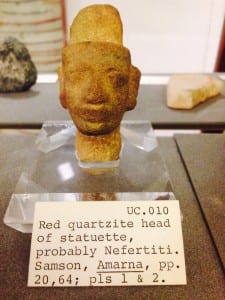

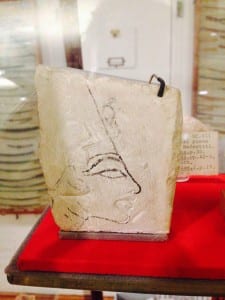

Could we not apply a similar logic to the objects in the Petrie Museum? How do we display the remains of a dead civilisation, and in what way a do we render them historically or immediately lifeless? The set of Fayum mummy portraits housed in this museum pose a suggestive example of just such a problem. Excavated by Flinders Petrie in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, these strikingly naturalist portraits were ‘part of the funerary equipment needed for entry into the afterlife’ for elite members of the Fayum people who lived in Egypt under Roman rule. Such information, we might think, animates these portraits; they are a record of the funerary practices of an ancient people, bringing to life the death-rituals of the past. However, the manner in which these portraits are displayed now and were displayed originally suggests something else.

Mummy Portrait, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology (UC19611)

Today, these panels sit alongside each other in a row: a set of faces painted in Greco-Roman style lined up in sequence, like the photo album of an ancient family. And Petrie himself first displayed these as if they were European art portraits, set upon the walls of a London room in 1889. Crucially, these two forms of display are made possible by the fact that these portraits are torn out from their funerary and material contexts. Each portrait was literally cut from the mummy to which they belonged. These portraits exist in a museum only by virtue of an act of violent de-contextualisation, which no amount of historical or cultural context can reverse or palliate. What was alive for the dead in the past, has been exhumed for the living today and in turn made museal.

Adorno’s reflections on “the museal” raise important questions about how we display objects in museums, the forms of contextualisation and de-contextualisation to which we submit these objects, and the historical and cultural forces their display reflects. It also mirrors long-running debates in the Humanities about how we should interpret all forms of cultural production. Rita Felski puts it this way: ‘Critics […] find themselves zigzagging between dichotomies of text versus context, word versus world, internalist versus externalist explanations of works of art.’ Scholars in the humanities simply do not agree about whether we should stick primarily to interpreting the objects themselves, or whether we need to focus on the social, political, linguistic, and historical contexts that gave rise to those objects.

This essay will not attempt to resolve these problems, but instead has attempted to draw attention to the way in which objects in a museum are involved in a seemingly irresolvable tension. What is easy to ignore, however, is how visitors to museums themselves respond to objects in ways that go beyond the pinched contestations of academic critique. Over four years of engaging with visitors across UCL’s three public museums, I have seen people respond the museum collections in ways that categorisation and critique cannot always account for. Visitors to the Grant Museum respond with both intellectual wonder and personal revulsion to the often grotesque preserved remains of 19th century science’s subjects; in the Petrie museum I have talked with people reflecting upon a divided sense of historical vertigo, ruminating upon the impossibility of knowing the lives of Ancient Egyptians, while at the same time marvelling at the uncanny sense of intimacy evoked by one’s proximity to the hair combs, sandals, and kohl pots of ordinary ancients. Responses to objects in UCL’s museums are never absolutely historically critical nor completely naïve. They are complex aggregates of both; mixtures or compounds of thinking, feeling, scepticism, and wonder. If I have learned anything from working in these museums it is that the necessary but sometimes leaden abstractions of academic criticism must always return to the organic complexity of living responses to museum objects.

Close

Close