Painted Skins & Butterfly Wings

By Gemma Angel, on 1 April 2013

by Gemma Angel

by Gemma Angel

When I first began my doctoral research into tattoo preservation three and a half years ago, I assumed that tattoo collections such as those held by the Science Museum in London were rare. Whilst collections of inked human skin are most definitely unusual, I was soon surprised and intrigued to discover that such objects exist in almost every museum archive, university anatomy department, or pathology collection that I have visited over the course of my research. The largest collections, of which the Wellcome Collection is the major exemplar, are dry-preserved and date from the 19th century – similar collections can be found across Europe, and the MNHN in Paris has a collection of 56 tattoos which are very similar to those in the Wellcome collection. Historically, these collections may be medical, anthropological, or criminological in origin.

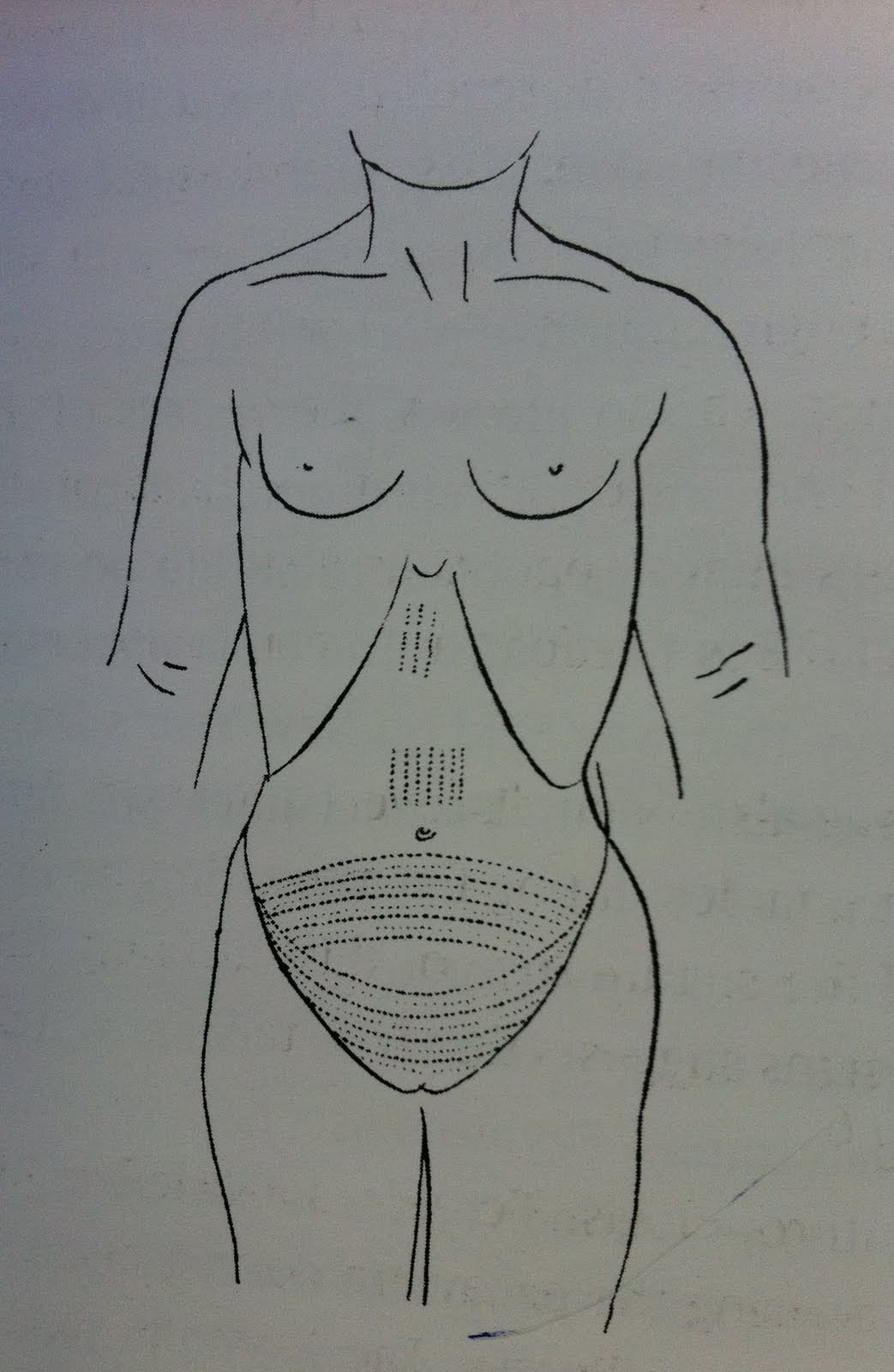

In anatomy and pathology collections, tattoo specimens tend to be wet-preserved and date more recently, usually from the early part of the 20th century anywhere up to around the 1980s. But why are these objects preserved in anatomy and pathology departments at all? There is of course nothing pathological about tattooed skin in itself – so it seems strange that specimens like the one pictured below are displayed alongside other pathological skin specimens such as cutaneous anthrax, fibromas, keloids and glanders. What, if anything, can be learned from these tattoos in medical terms? Or are these striking collections of decorated human skin merely objects of curiosity? Often, the simple answer is that they are a little bit of both…

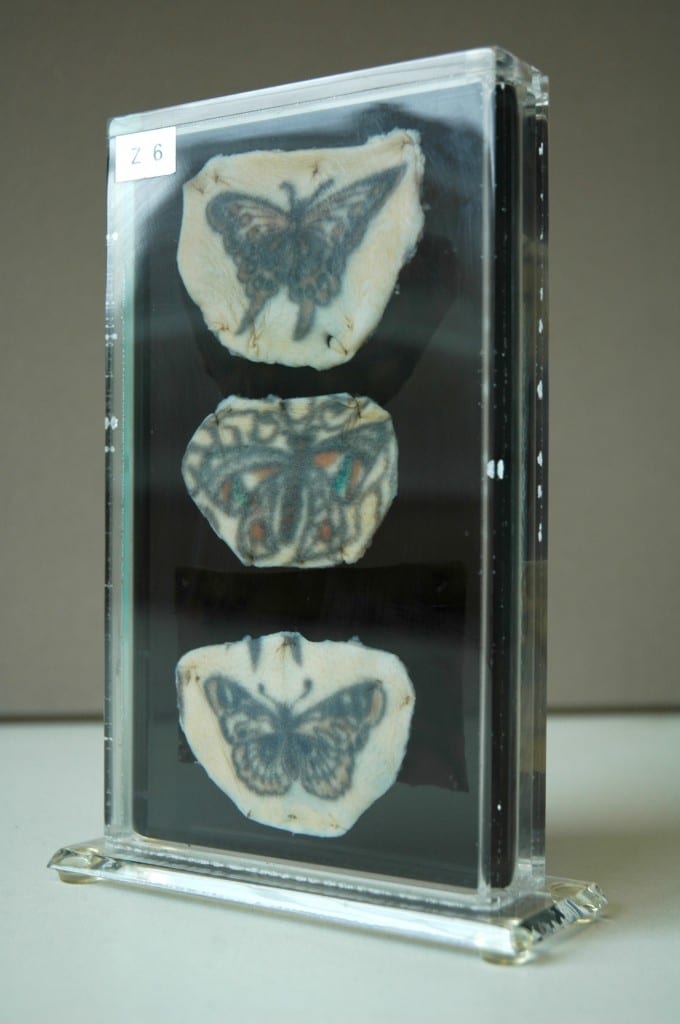

The collection of tattoos pictured here are a case in point. These particular tattoos belonged to one individual, whose very brief case notes have been recorded and retained along with the specimen in UCL Pathology Collections. The notes provide an intriguing glimpse into the life of the individual to whom the tattoos belonged, as well as revealing something of the clinical interests and collecting practices of the doctor who preserved them:

From a man aged 79 years who had earned his living for many years as the Tattooed Man in a circus. His entire body, except for the head and neck, hands and soles of his feet, was covered with elaborate tattoo designs. He died of peritonitis due to a perforation of an anastomatic ulcer … In tattooing, fine particles of pigment are introduced through the skin, taken up by histiocytes and become lodged in the tissue spaces of the dermis. Pigment also passes to the regional lymph glands via the lymphatics. In this case, all the superficial lymph nodes were heavily pigmented.

It is clear from these brief comments that the nature and extent of this man’s tattoos were indeed of anatomical interest to the medical practitioner: The tattooed man had been so extensively tattooed that gradual migration of ink particles resulted in the collection of pigment in the lymph glands. This demonstrates that although tattoo ink is trapped permanently under the skin following healing, it does actually travel within the body over time, filtering into the body’s tissue drainage system, and collecting in the lymph glands. Whilst this is certainly an interesting anatomical observation, it is not the pigmented lymph glands that the doctor has chosen to preserve, but rather the tattooed skin itself. Without these accompanying case notes, we would never have known that this man’s tattoos had exerted any effect on another of the body’s organs and systems at all.

Reverse panel of tattooed human skin

specimen Z6, showing tattoos of a

butterfly and a flying fish.

UCL Pathology Collections.

Photograph © Gemma Angel.

It would be equally impossible to know whether or not these were the only tattoos he possessed – or indeed, if they all necessarily belonged to the same person. There are strong stylistic similarities between the butterfly motifs, suggesting the work of a single tattooist, or perhaps that the individual motifs were part of a larger design. But just how large or complex the design may have been, we certainly cannot tell just by looking at these 5 small tattoos. We know that they belonged to a 79-year-old man, who made his living as a Tattooed Man, only because the doctor tells us so. He or she also tells us that his body was covered in tattoos – yet only 5 small pieces have been preserved. Five carefully selected motifs, chosen by the doctor from an already complete collection, which provided the livelihood and told the life story of one unnamed man. What selection criteria did the pathologist adopt when deciding which tattoos to preserve, and which to consign to the grave? The manner in which the specimens have been excised and mounted are strikingly reminiscent of a lepidopterist‘s collection of butterflies – could this reflect the personal collecting interests of the pathologist, or perhaps even the Tattooed Man himself? Both the pathologist and Tattooed Man alike chose these butterflies – did they also share a passion for lepidoptery?

Many people will be familiar with the kind of insect specimen displays that are a staple of natural history collections – the old 19th century museum cases containing neat rows of pinned and mounted moths and butterflies, neatly organised according to subspecies and morphological characteristics. The tattooed butterflies share some remarkable similarities with these entomology collections; they are arranged one above another, and “pinned” to a support with small surgical stitches. Unusually for specimens found in pathology collections, this support is a slightly translucent black. This appears to be a deliberate choice on the part of the pathologist – the black perspex provides a contrasting ground for the display of tattoos on opposite sides of the vitrine, such that they do not visually detract from one another. These aesthetic choices suggest a nuanced interest in the collection and display of these specimens, which goes far beyond a straightforward medical interest in the anatomy of the tattoo. From the limited case notes and analysis of the specimen itself, we can learn something about the pathologist’s interest in the tattoo, but we are still no closer to being able to answer the fundamental question – why collect tattoos at all?

There is no part of the body able to register the history of a life lived so much as the skin: wrinkles, scars and lines all map out our lives on the surface of our bodies as we age. The tattoo reinforces this unique capacity of the skin to record the traces of our experience, in the conscious act of permanently inscribing memory in skin. The pathologist, uniquely acquainted with death by virtue of their specialism, is perhaps best positioned amongst medical professionals to appreciate the peculiar relationship of the tattoo with mortality. It is a trace of the subjectivity of the deceased that is capable of outliving them, akin to a photograph or written memoir. From this point of view, it no longer seems surprising that tattoos are so often found in pathology collections; perhaps the pathologist who collected the Tattooed Man’s butterflies simply wished to preserve a small part of a colourful and remarkable life.

[analytics-counter]

Close

Close