Doctors, Dissection & UCL

By Gemma Angel, on 21 January 2013

by Sarah Chaney

by Sarah Chaney

A visit to the current Museum of London exhibition, Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men (on until 14 April 2013), brought to mind the recent Buried on Campus exhibition in the Grant Museum. Several of us have previously blogged about reinstating the stories of the forgotten dead, as well as the issues around the display and interpretation of human remains in a museum context. As I myself wrote, the disinterrment of human remains is not unusual during building work: the Museum of London exhibition focuses on the excavation of the former Royal London Hospital burial site, during recent improvement works. The bones found showed traces of a variety of practices, including dissection for autopsy, as well as marks made during surgical practice and articulation for the creation of teaching specimens.

Dissection, particularly in the case of medical teaching, was often linked to artistic practice. Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men opens with the grisly plaster cast of James Legg, hanged for murder in 1801. Legg was subsequently flayed and posed as if crucified: a collaborative project between artists Benjamin West and Richard Crossway, and sculptor Thomas Banks, who believed that most depictions of Christ’s crucifixion were anatomically incorrect (for more on the Anatomical Crucifixion see Gemma Angel’s post). Rather less theatrically, anatomical drawings and textbooks were also created directly from dissection practice. During a recent session in the Art Museum, I discussed with visitors the way in which anatomy textbooks create stylised images, removing certain body parts in order to emphasise others. Students re-created these images for themselves: first with the corpse, then in their own sketches, re-interpreting the body in a way that made sense for their practice.

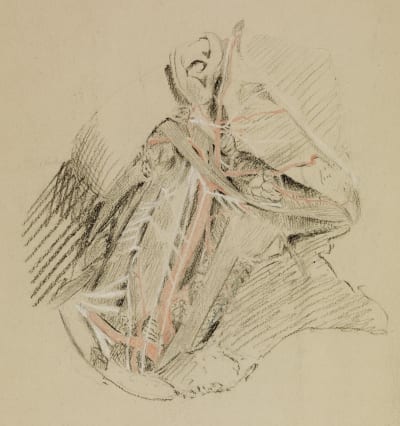

Amongst the UCL Art Collections are a number of student sketches of the famous surgeon Joseph Lister (1827 – 1912), well-known for his introduction of antiseptic techniques into surgical practice. Born in Essex, Lister came to UCL in 1844, initially as a student of the arts. After graduating, however, he subsequently turned his attention to medical studies, continuing at UCL until he gained his M.B. in 1852. The sketches in the collection mainly date from 1849-50, produced as part of Lister’s studies. The techniques used indicate some of the interesting artistic choices available to anatomical illustrators: perhaps also the influence of Lister’s varied education and interests. The sketch above, for example, was made on tinted paper, which enabled the young Lister to highlight structures using white chalk. This emphasis, along with the effective use of colour (in this instance, major blood vessels are depicted in red, standing out clearly in an otherwise monochrome drawing), enables quick and easy recognition of bodily structures, adding depth to the sketch. For an un-trained eye, the mass of tissues within the human body could not be read in such a manner. The ability to render the three-dimensional body in a series of recognisable images – and then understand the physical body through such images – was as important as surgical skill.

The huge variety of techniques for anatomically representing the human body is also evident elsewhere in the UCL Collections. The Physiology Collection includes a volume of the Edinburgh Stereoscopic Atlas of Anatomy, published in 1905. Stereoscopy became a popular technique of representing three-dimensional structures from its inception in the 1840s. Two offset photographs or other images are presented to the viewer which, when viewed through the stereoscope, are seen separately by the left and right eye. As occurs in ordinary vision, the brain combines the images perceived by both eyes; in the case of stereoscopy, giving the illusion of three-dimensional depth. The Edinburgh Atlas aimed to use this technique to represent photographs of dissections in a manner closer to that seen in the three-dimensional human body than simple sketches. Bulky and expensive, the success of the Atlas was relatively limited. It still serves, however, as an unusual reminder of the way in which the human body has continued to require anatomical translation.

Close

Close