TAXONOMIES OF BONES AND POTS: THE PETRIE POPS UP AT THE GRANT MUSEUM

On the 13th of February, objects and ideas from the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology “popped-up” in the neo-Victorian surrounds of the Grant Museum of Zoology in an event that sought to explore some of the ways in which archaeologists and biologists both engage in the act of classification and taxonomy. I attended this event in the guise of ‘Student Engager’, with the intention of sharing with visitors my own research on Darwinian evolution and literature. More on this later, but for now, it is perhaps a good idea to examine the procedure of taxonomy itself, as it relates specifically to biology and archaeology.

Taxonomy (from the Greek ‘taxis’ meaning ‘order and ‘nomos’ meaning ‘knowledge’) refers broadly to the act of (unsurprisingly) the ordering of knowledge and to the examination of the principles that underlie these logically ordered schemata. It is this process of ordering that the proponents of both ancient Egyptian archaeology and zoology practice – albeit in subtly different ways.

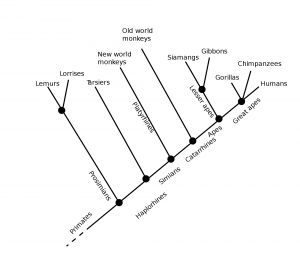

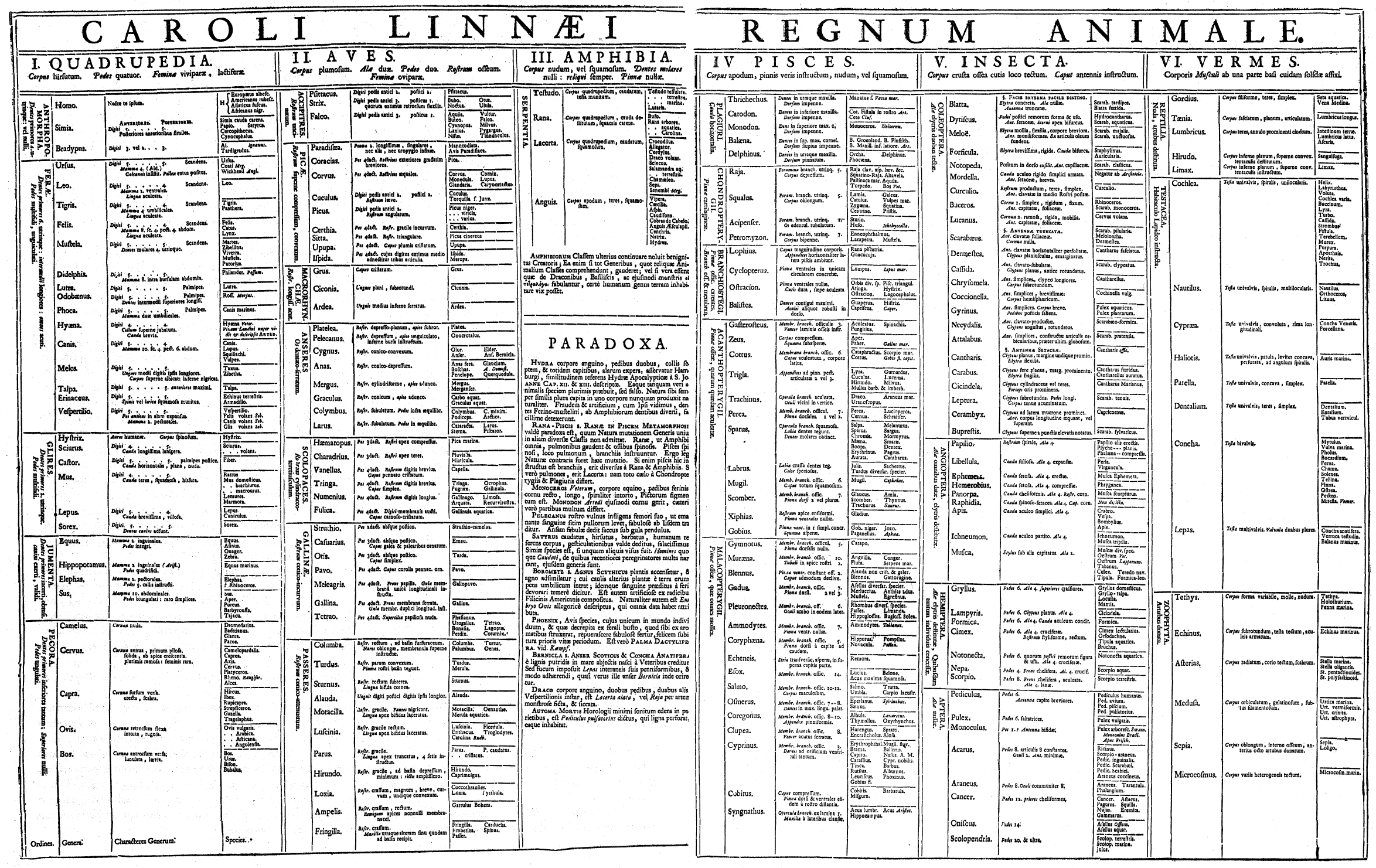

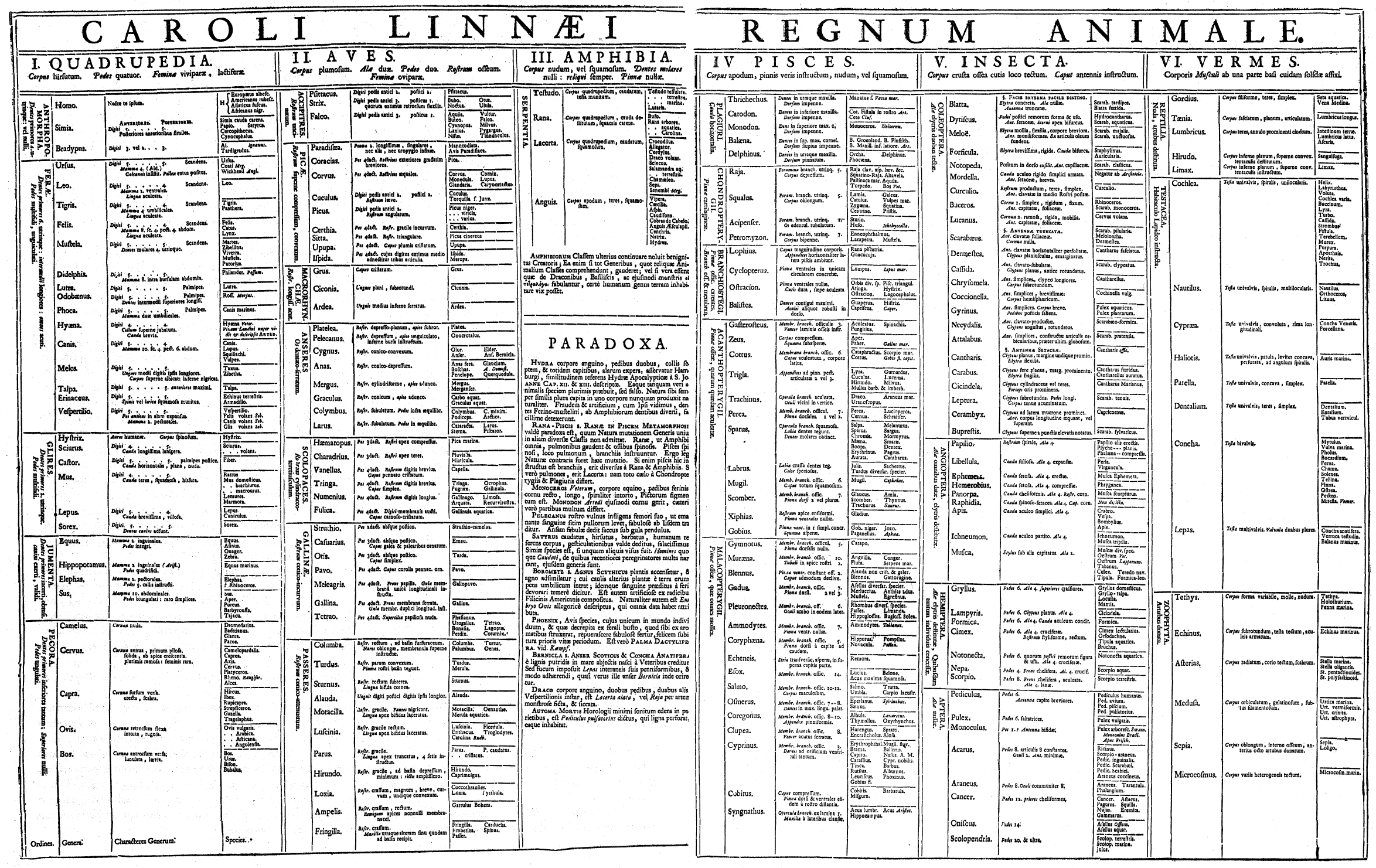

Taxonomy in biology, as we understand it now, is widely considered to derive from the work of the Swedish 18th Century naturalist Carolus Linnaeus. His seminal work in taxonomy, most famously given expression in Systema Naturae (1735), has bequeathed to us a method of biological classification, the finer details of which are now scientifically inaccurate, that to some extent lives on in popular thought (think of the game “Animal, Plant, or Mineral”) and whose basic outline persists in biology to this day. Linnaeus divided the natural world into three distinct types or ‘Kingdoms’, animal, plant, and mineral, and divided each of these into classes, with those categories dividing in turn into orders, families, genera, and species.

- Regnum Animale – Systema Naturae

Click to zoom

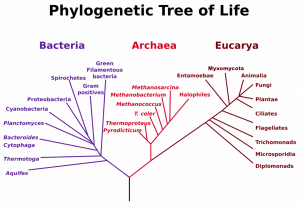

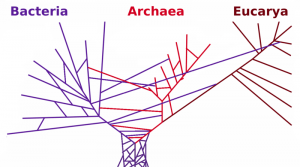

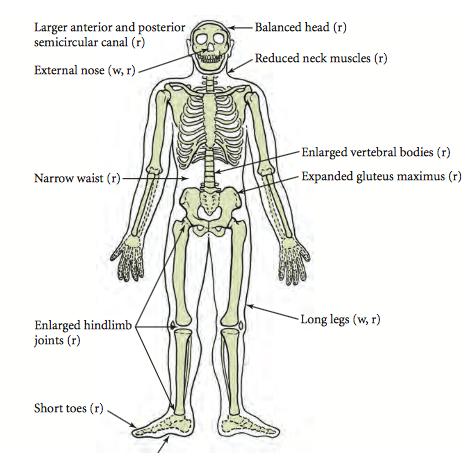

Today, biological classification requires a more complex, nuanced system, in which there are six ‘kingdoms’, subsumed under the category of three ‘domains’ of life and take into account another category of life within this schema, the phylum. Moreover, the Linnaen classificatory system has given way to the Darwinian ‘Tree of Life’ as the dominant visual representation of the natural world, as evidenced by the current exhibition in the British Library that examines the nature of the visual representation of science: one installation in particular allows us to explore with touchscreen techonology, in great detail, the natural world through navigating this ‘Tree of Life’ and has a profoundly disorienting effect on our image of our human selves as the centre or pinnacle of the natural world. Homo sapiens in this model occupy an obscure, diminutive branch amongst the great, entangled, and monstrously abundant foliage of other species.

- ‘Tree of Life’ – Origin of Species, 1859

Yet despite the insistence of the dynamic, non-hierarchical schema of the Darwinian ‘Tree of Life’, the basic hierarchical ranking of Linnaean taxonomy persists (necessarily) in contemporary biology. Without this “ordering” of knowledge, with its embedded hierarchies and rankings, biological classification would be a disordered chaos. How then does this taxonomic procedure play out in other fields, distinct from biology?

While the significance of taxonomy is evident (and its history well known) in biology, the taxonomic aspects of archaeology are perhaps not as widely appreciated. The case of Flinders Petrie, the founder of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology at UCL, provides us with a particularly apposite opportunity to excavate the function and significance of taxonomic classification in archaeology. Amongst Petrie’s most crucial contributions to archaeology are his schematic, chronological sequences of ancient Egyptian pottery. Petrie, faced with an abundance of predynastic pottery, collected along the Nile at various locations, needed a method of placing these pots in chronological order. Unlike the distinctly un-scientific methods of some of Petrie’s predecessors for whom the act of archeology was partially mythic in its reconstruction of the past, Petrie paid specifically close attention to the morphology of the objects with which he was faced and treated these morphologies as, what we call today, data-sets. Based on the assumption that the morphologies of pottery changed over time (in an almost evolutionary fashion), Petrie was able, via a complex mathematical process, to systematize and sequence the chronological order creating, in effect, a taxonomical method of dating pots. Both Petrie’s skill as a mathematician and diligence as an archaeologist is underlined here as, today, this statistical approach is undertaken using computers only – the complex arithmetic required simply taking too long for humans. The consequences of Petrie’s methodology – what is now called seriation – on the discipline of archaeology were and still are profound. The process is an important method in contemporary archeology and, in particular, it revolutionized our understanding of the timeline of Egyptian history, all through his taxonomic analysis of pottery.

https://twitter.com/LatentLaziness/status/434023358943207424

It was these very histories and methods of taxonomy in biology and archaeology that provided the crucial link between the Petrie and Grant Museums, and in turn provided the subject matter and theme of the event which I attended. Visitors were invited to engage in a number of taxonomic activities: reconstructing the shattered sequence of Flinders Petrie’s classification of pots, re-connecting and correctly identifying the scattered skeletal remains of a gorilla, and placing ancient Egyptian pots in their correct chronological order. These acts of reconstruction and identification, of the re-assembling of broken sequences and structures, stress the importance of taxonomy and classification in both biology and archaeology – disciplines whose methods, goals, and data-sets overlap in the fields of anthropology and osteo-archaeology. Moreover, it invites the participant to engage in the very ordering of knowledge out of disorder that underlies the procedure of taxonomy (albeit without the complex statistical mathematics). By the same token, taking part in a re-construction allows us to consider the implications of breaking up and disrupting these structure, of the deconstruction of systems of ordered classification.

My own research as a PhD student in UCL explores the way in which reading the work of Charles Darwin can provide us with new critical and theoretical insight into works of literature – and how reading works of literature have a reciprocal effect on our readings of Darwin. I referred to the Darwinian ‘Tree of Life’ earlier in this blog and it is to this I return now. Previously, I suggested that the tree model of life provided us with a more nuanced and dynamic method of ‘ordering’ our knowledge of the natural world than that of the Linnaean classificatory system. This view of the natural world, I stated, was profoundly decentring: homo sapiens are removed from our self-appointed place at the top of the hierarchy of species. And yet, does Linnaeus specifically place humans at the top of a hierarchy? Looking at the table of species published in Systema Naturae, there is a distinct echo of the deliberate subordination of all animals to the supremacy of man that has occurred in older visual and conceptual models of the natural world. Linnaeus’ table puts us (‘anthropomorpha’) at the top of the table, bestowing us with the title of “Number 1”. This repeats the schema that has been passed down through Western thought since Aristotle in the Scala Naturae, or the “Chain of Being” in which humans existed only below God in the grand hierarchy of all species. In this context, Darwin’s arboreal structuring of the natural world, with the human race being afforded no greater a position than a mouse or a mollusc is defiantly radical, shunning the accepted wisdom of all naturalist and biological thought since Ancient Greece. Moreover, the categories in Darwin’s model of life, the taxonomic leaves that sit upon the branches of genetic connection, are themselves unstable and subject to constant change.

- Chain of Being – Rhetorica Christiana 1579

Darwin himself, writing in The Origin of Species in 1859 wrote:

“Naturalists try to arrange the species, genera, and families in each class, on what is called the Natural System. But what is meant by this system? Some authors look at it merely as a scheme for arranging together those living objects which are most alike, and for separating those which are most unlike; or as an artificial means for enunciating, as briefly as possible general propositions …”

Darwin, it seems, wishes to question the very substance and authority of this natural system, inaugurated by Linnaeus. For him, it is a necessary evil – an unwanted and ‘artificial’ ossification of the dynamism and change inherent in biological life that is nevertheless required for order and brevity in biology.

Yet, he goes further in his critique of classificatory systems:

“…we shall have to treat species in the same manner as those naturalists treat genera, who admit that genera are merely artificial combinations made for convenience. This may not be a cheering prospect; but we shall at least be freed from the vain search for the undiscovered and undiscoverable essence of the term species…”

The term species for Darwin is an arbitrary linguistic imposition on an organic form that by definition is never stable and always in a state of flux. He, like those who criticize the worst vagaries of cultural, linguistic, and philosophical postmodernism, sees in this biological relativism something to be maligned – a state of existential flux that results only in the melancholia of unstable and incomplete knowledge. Yet, in this he sees the prospect of an end to a “vain search”: the search for “essence”, linguistic, philosophical, and biological. Rather, Darwin would assert, we should instead attend to the ‘entangled bank’ of differences, to which he refers towards the end of Origin of Species, that make up the natural world rather than vainly trying to categorise and essentialise all of organic existence.

What if anything, does this literary critical digression of mine have to do with the taxonomical procedures of Flinders Petrie? Or, indeed, with his chronological series of pots? It might be worth asking, instead, what do Petrie’s series of pots tell us about the humans that made them? Or indeed about the relationship these humans had to the form of the pots that they created? It is my job as a literary critic to focus on ‘difference’ in literature and art; to attend in detail to the specific and subjective detail of single works of culture and their relationships with history, with other works of art, with texts, and with the individuals that created them. Taxonomy, the ordering of knowledge, on the other hand has a tendency to subordinate difference at the hands of “order”. On an instrumental level, this ordering process is vital for biology to operate – we could not simply throw our hands up give in to the desire to say that, say, tigers are contingent and temporary balls of matter in a state of constant flux and, therefore, should not be named! Yet, when it comes to the creative products of human hands and minds, there is an ethical dimension that should be attended to: to subordinate difference in art and culture is to subordinate individual difference in human life.

Francis Galton, a cousin of Darwin, and a colleague and acquaintance of Petrie, who worked at UCL in the early 20th C saw in the science of taxonomy, underlined by a misreading of Darwinian evolution and heredity, the potential to categorise and order human society according to his terms. He differentiated between the European races and the ‘lower races’ of man, creating, in effect, a taxonomy of human life. Not only is this scientifically incorrect, but the very act of naming and of creating order in doing so does a violence to those whom it names – restricting their existence to a category in which variance and difference within that group cannot be registered and asserting an unquestioned hierarchy of races, similar to that of the Systema Naturae. A distinctive passage from Galton’s work Hereditary Genius elucidates his views on the hierarchies of life:

“The natural ability of which this book mainly treats, is such as a modern European possesses in a much greater average share than men of the lower races. There is nothing either in the history of domestic animals or in that of evolution to make us doubt that a race of sane men may be formed who shall be as much superior mentally and morally to the modern European, as the modern European is to the lowest of the Negro races”

Galton is considered to have inaugurated the pseudo-scientific practice of eugenics, a discipline which espoused the improvement of human ‘stock’, the creation of a ‘race of sane men’, through selective breeding and other methods, the very name of which, today, can only be used in pejorative terms due to its racist foundations and invidious implications in the 20th Century.

These are the dangers of taxonomy when applied, misguidedly and without reflection, to human culture. Certainly, it is not my argument that taxonomy or order is inherently wrong. It was, however, my intention at the event held in the Grant Museum on the 13th of February to try and disrupt and disorder the usual ways in which we think about taxonomy in all fields.

Interestingly, Darwin, a scientist, like Galton, gives us an elegant means of resisting the worst vagaries of taxonomical essentialism. However it is only through a detailed and sensitive reading of Darwin’s writing that this can emerge from his texts. In other words, in order to see Darwin as holding ambivalent and philosophically interesting views on taxonomy and classification, it was necessary to ignore the taxonomical classification of Darwin as “Scientist” and “Biologist” and instead attend to the specific literary detail of his work.

Works cited and further reading (in no particular order):

Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, ed. by Gillian Beer, New edition (OUP Oxford, 2008).

Francis Galton, Hereditary Genius, (London: Macmillan, 1892).

Debbie Challis, The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie, (London: Bloomsbury, 2013)

Michel Foucault, The Order of Things, (London: Routledge, 1989)

Close

Close