Of Foetuses & Fibroids: the Accidental Foreign Body

By Gemma Angel, on 8 April 2013

by Lisa Plotkin

by Lisa Plotkin

As our current exhibition in UCL’s north cloisters demonstrates, “foreign bodies” may take many forms, as well as being continually redefined throughout history. Putting it simply, the term “foreign body” in medicine usually refers to an external object introduced into the body that isn’t supposed to be there. As my colleague Dr. Sarah Chaney notes in her recent blog post, some of the most common foreign objects uncovered from the bodies of 19th and early 20th century patients were coins, safety pins, buttons and needles. These objects could enter the body accidentally or with purpose. Medical instruments or tools, for example, were on occasion accidentally lost inside the patient’s body during an operation. For those Seinfeld fans out there, think back to the “junior mint” episode. However, it was neither pins, mints or instruments which were the subject of a 1939 article in the British Medical Journal devoted entirely to foreign bodies. Rather, Dr. A. H. Charles, obstetric registrar at St. George’s Hospital, zeroed in on one particular foreign body that was with some frequency discovered in the female bladder: slippery elm bark. It may surprise some readers to discover (as it certainly did Dr. Charles), that slippery elm bark was commonly used as an abortifacient. In fact, it is still used by women to induce abortion today.[1] Writing on elm bark as a foreign body inside the bladder, Dr. Charles observed:

Five cases in which a piece of elm bark was used have been reported in detail previously, and in all of these the body has remained undiscovered for some time, until its removal suprapubically after calculus formation had taken place, causing symptoms leading to its discovery. Why the bark of this noble tree should be so popular is difficult to understand.[2]

Called “slippery” elm because when it gets wet it becomes slippery, this type of elm bark has traditionally been used to cause early uterine contractions and induce labor. The bark is inserted into the cervix where it then absorbs water and expands, dilating the cervix and triggering contractions. Needless to say, this procedure was not always successful and could cause life-threatening infections. Occasionally the bark could end up in the bladder by mistake, which is what Dr. Charles had observed. For many of the women who mistakenly inserted the slippery elm into their bladders, there the bark most likely stayed, unless a severe medical problem compelled them to seek medical attention. No doubt for many of the women attempting to self-abort, their experience with slippery elm was less than satisfactory and could have proven fatal.

Accidental or intentional abortion occurred with a lot greater frequency in the 19th and early 20th centuries than some might imagine, and was inextricably wrapped up with both the idea and concrete reality of “foreign bodies.” For many, the coat hanger is the ultimate symbol of a foreign body inserted into the uterus to cause abortion. Still others may think of obstetric forceps as the foreign body which has caused thousands of fetal deaths during delivery. But what about uterine fibroids? How many abortions have they caused, and can they be regarded as foreign bodies if they are naturally occurring? A uterine fibroid is a benign tumour of the uterus, commonly found in women of reproductive age. Most fibroids are asymptomatic and therefore, most women are never aware that they even have one. However, on occasion these fibroids can cause health complications or interfere with pregnancy. Before the advances of late 19th century abdominal surgery and gynecology, uterine fibroids were not treatable. However, by 1916, obstetric surgeon Sir. John Bland-Sutton was able to boast that “uterine fibroids are common tumours; so common and troublesome that I have removed the uterus in 2,000 women.”[3]

From his experience performing hysterectomy on thousands of women a theme emerges: uterine fibroids closely mimic pregnancy in a variety of ways, and it is difficult – sometimes impossible – to distinguish between the two. Writing of this unfortunate similarity in 1913 Bland-Sutton observed, “A large sub-mucous fibroid produces similar changes in the uterus to those set up by the growth of the fetus […] Women with large sub-mucous fibroids are more or less in a condition resembling chronic pregnancy.”[4] What this similarity meant – and what gynecologists and obstetricians of the time openly acknowledged – was that sometimes a hysterectomy was performed to remove a fibroid that either never existed in the first place, or was also sitting alongside a feotus, masking a pregnancy. Either way, an abortion was performed.

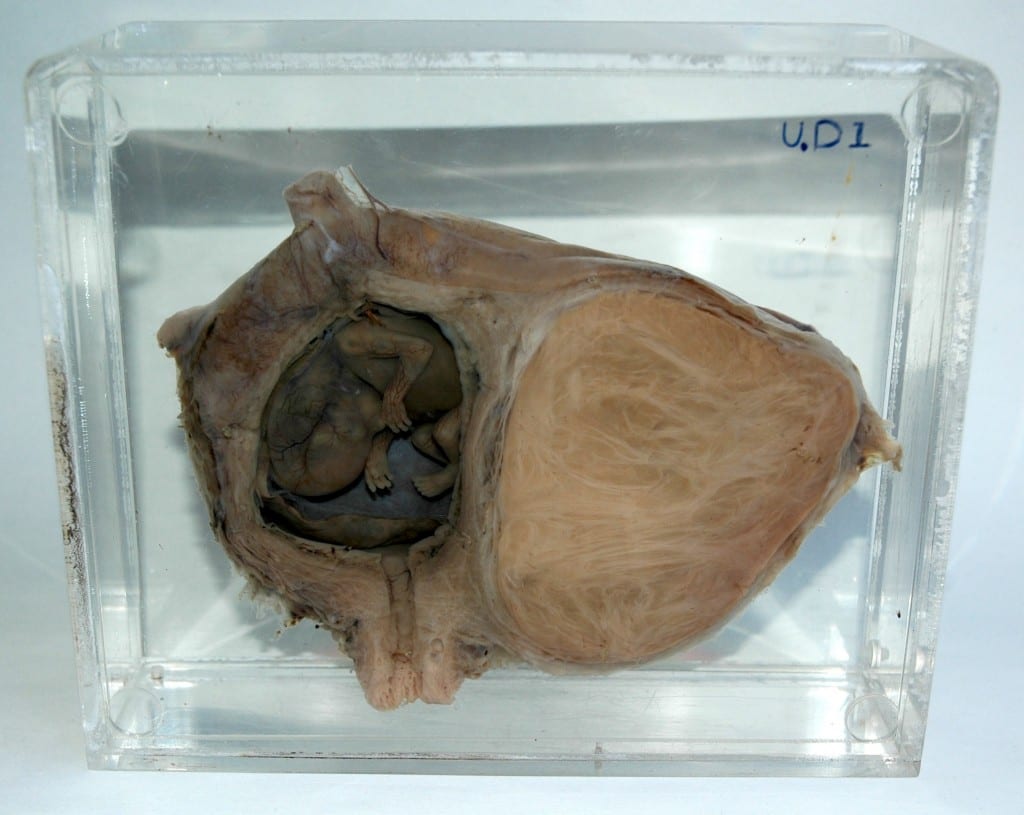

The photograph below demonstrates the reality of such surgeries. This particular specimen belongs to UCL Pathology Collections, and is currently on display in the Foreign Bodies exhibition. The anonymous woman patient underwent a hysterectomy most likely sometime in the early 20th century, in order to remove the sizable uterine fibroid, which can be seen on the right side of the image. However, on closer examination of the image, we see on the left side a preserved feotus, frozen in development, somewhere between 8-11 weeks. It is unclear whether this woman or her doctor even knew she was pregnant.

Such examples abound in medical literature, and Victorian and Edwardian gynaecologists, obstetricians, and surgeons spoke of them with little or no censure. It was all a part of the surgical trial and error that they were practicing. The feotus was sometimes viewed as a necessary casualty in removing a potentially life-threatening fibroid. Either way, be it by slippery elm, by accident, or with purposeful intent, the feotus was removed as a foreign body, like any other. By examining the medical establishment’s attitudes towards fibroid removal we catch a glimpse into one way the feotus, and the experience of pregnancy in general, was understood in the past.

References:

[1] David A Grimes, Janie Benson, Susheela Singh, Mariana Romero, Bela Ganatra, Friday E Okonofua, Iqbal H Shah. “Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic.” The Lancet Sexual and Reproductive Health Series, October 2006.

[2] British Medical Journal, 29 July 1939.

[3] Sir John Bland-Sutton, “A Clinical Lecture on 200 Consecutive Hysterectomies for Fibroids Attended With Recovery” reprinted British Medical Journal, 4 July 1916.

[4] Sir John Bland-Sutton, “The Visceral Complications Met With Hysterectomy for Fibroids and the Best Methods for Dealing With Them” British Medical Journal, 1 November 1913.

Close

Close