What is the relationship between frogs and fertility?

By Hannah B Page, on 10 July 2018

During my first few weeks as a student engager I began to notice the presence of frogs… everywhere. I saw them in various forms and objects in the Petrie Museum, and found frog and other amphibious specimens in the Grant Museum. The Surinam toad quickly became one of my favourite objects to show visitors—the female stores her eggs in her back, and they then burst through the skin when fertilised (Fig 1.). As you can imagine, when you tell people this, you get a mixed response. I took this all as a sign and decided I should do a bit of splashing around in the amphibian research pool and dedicate my first blog post to them.

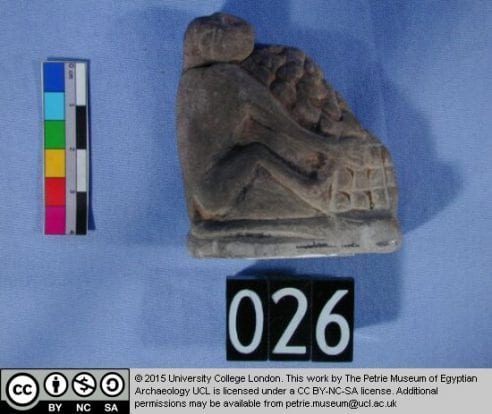

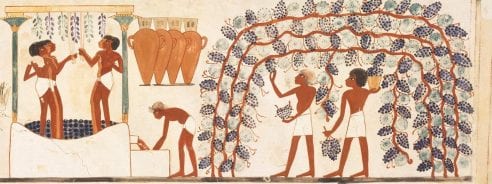

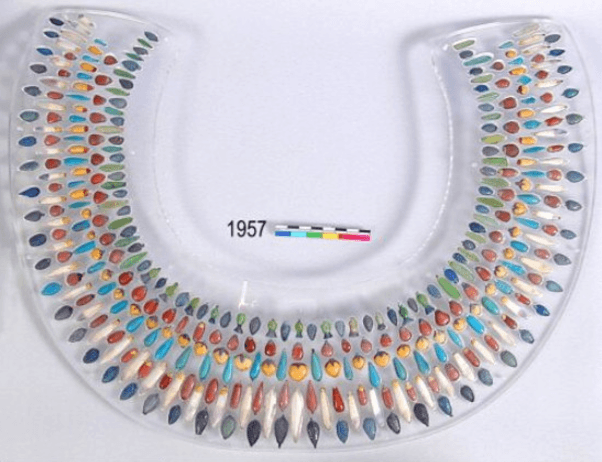

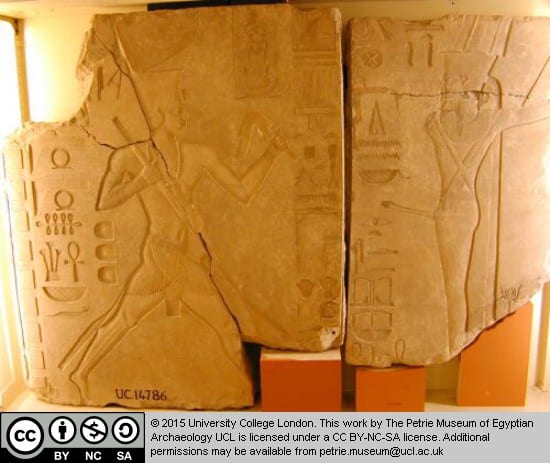

What became immediately obvious when I started to do some digging is just how common frogs are in cultural and religious belief systems. Frogs are used as characters in folk law and in fairy tales—just think of the frog prince in the Grimm stories—but I discovered that their use in religion and culture goes back much, much further. Both the ancient Egyptians and the Mesopotamians saw the frog as a symbol of fertility and life giving. This connection is obvious when you understand the importance these past civilisations gave to the rivers that flowed through their lands. The Nile, Tigris and Euphrates rivers are hailed as the facilitators of the fertile lands that made the development of the first major cities and the centralised hierarchical societies that lived there possible. So the frog, as a watery symbol of the life-giving waters, was then depicted in reliefs, sculpture and objects. One such object is a beautifully crafted, smooth limestone frog in the Petrie Museum (Fig. 2). In fact, frogs are such a strong and consistent symbol in ancient Egyptian culture that they are found depicted in important and specialist objects from the predynastic Naqada periods to the Roman period—some 4,500 years.

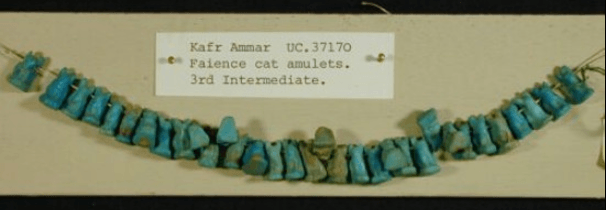

The Egyptians even depicted a goddess, Haqet, in the image of a frog. Unsurprisingly Haqet is the goddess of fertility and is often depicted either as a frog or in human form with the head of a frog. Amulets were then fashioned in the shape of frogs/Haqet, and were worn, providing fertility to the wearer.

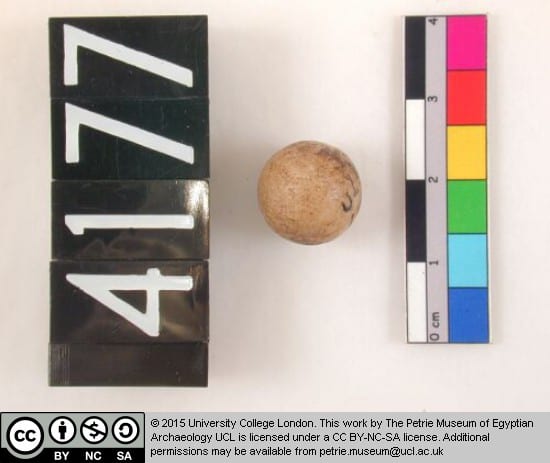

Frogs have also been the subjects of art in other areas of the world as well, for example for the Moche culture of Peru (Fig. 3). The frog species found in the Amazon basin are the most numerous and some of the most deadly, including the poison dart frog who has enough deadly toxin to kill between ten and twenty grown people. Interestingly enough, in Moche society they were also associated with fertility and growth, but with their toxicity (and sometimes hallucinogenic quality), it is thought that their symbolic meaning stretches far beyond this interpretation.

However in Europe, frogs and toads haven’t always been seen in such a positive light. The prince in the frog prince was cursed and turned into a frog as punishment, and in the epic biblical poem Paradise Lost, John Milton depicts Satan as a toad poisoning Eve.

So, their social and symbolic importance is well recorded, but what about their biological history? For this I interrogated the case in the Grant Museum dedicated to them. Frogs and toads it seems started life in the Triassic period, some 240 million years ago. The museum even has a cast of an early German species (Palaeobatrachus) that lived around 130-5 million years ago. What is also striking about the frog is its wide native distribution across the globe, from Europe, to the Americas, Africa to Australasia. So it is unsurprising that these springy species have such an important and consistent cultural presence worldwide.

Finally in my research I discovered that the study of the relationship between human culture and amphibians even has a name: ethnoherpetology. Clearly we have a long and intimate history with our croaky friends.

So next time you’re close by, why not hop into the Grant or the Petrie Museum to see how many frogs you can find?

Close

Close