Sports in the Ancient World

By Stacy Hackner, on 24 January 2017

I’ve written previously here about the antiquity of running, which was one of the original sports at the ancient Greek Olympics, along with javelin, archery, and jumping. These games started around 776 BC in the town of Olympia. What came before, though? What other evidence do we have of ancient sports?

Running is probably the most ancient sport; it requires no gear (no matter how much shoe companies make you think you need it) and the distances are easily set: to that tree and back, to that mountain and back. Research into the origins of human locomotion focus on changes to the foot, which needed to change from arboreal gripping to bipedal running and bearing the full weight of the body. A fossil foot of Ardipithecus ramidus, a hominin which lived 4.4 million years ago, features a stiffened midfoot and flexible toes capable of being extended to help push off at the end of a stance, but has the short big toe typical of great apes. Australopithecus sediba, which lived only 2 million years ago, had an arched foot like modern humans (at least not the flat-footed ones) but an ankle that turned inwards like apes. Clearly our feet didn’t evolve all the features of bipedal running at once, but rather at various intervals over the past 4-5 millennia. Evidence of ancient humans’ distance running is equally ancient, as I wrote about previously. Researchers Bramble & Lieberman have posed the question “Why would early Homo run long distances when walking is easier, safer and less costly?” They posit that endurance running was key to obtaining the fatty tissue from meat, marrow, and brain necessary to fuel our absurdly large brains – thus linking long-distance running with improved cognition. In a similar vein, research into the neuroscience of running has found that it boosts mood, clarifies thinking, and decreases stress.

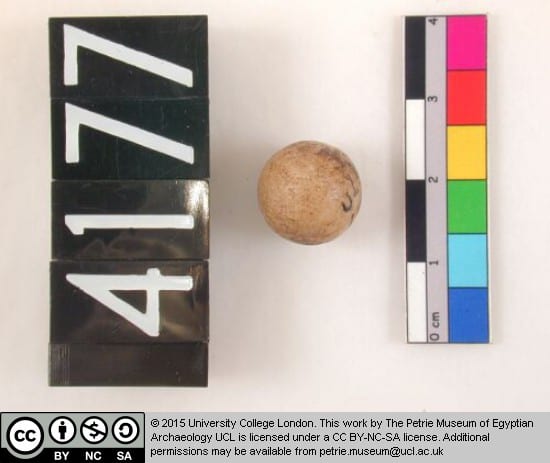

Feats of athleticism in ancient times were frequently dedicated to gods. Long before the Greek games, the Egyptians were running races at the sed-festival dedicated to the fertility god Min. A limestone wall block at the Petrie depicts King Senusret (1971 BCE) racing with an oar and hepet-tool. The Olympic Games, too, were originally dedicated to the gods of Olympus, but it appears that as time went on, they became corrupted by emphasizing the individual heroic athletes and even allowed commoners to compete. There were four races in the original Olympics: the stade (192m), 2 stades, 7-24 stades, and 2-4 stades in full hoplite armor. It should be mentioned that serious long-distance running, like the modern marathon, was not a part of the ancient games. The story of Pheidippides running from the battlefield at Marathon to announce the Greek victory in Athens is most likely fictional, although the first modern marathon in 1896 traced that 25-mile route. The modern distance of just over 26 miles was set at the 1908 London Olympics, when the route was lengthened to go past Buckingham Palace.

Limestone wall-block showing King Senusret I running the sed-festival race before the god Min. Courtesy Petrie Museum.

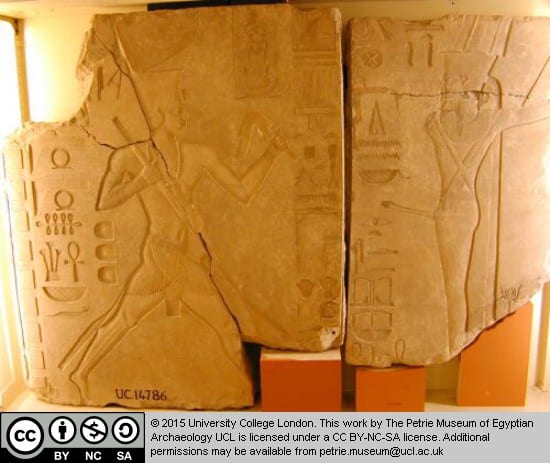

Wrestling might be equally ancient. It’s basically a form of play-fighting with rules (or without rules, depending on the type – compare judo to Greco-Roman to WWF), and play-fighting can be seen not only in human children but in a variety of mammal species. In Olympic wrestling, the goal was to get one’s opponent to the ground without biting or grabbing genitals, but breaking their fingers and dislocating bones were valid. Some archaeologists have tried to attribute Nubian bone shape – the basis of my thesis – on wrestling, for which they were famed. Another limestone relief in the Petrie shows two men wrestling in loincloths. Boxing is a similar fighting contest; original Olympic boxing required two men to fight until one was unconscious. Pankration brutally combined wrestling and boxing, but helpfully forbid eye-gouging. It may be possible to identify ancient boxers bioarchaeologically by examining patterns of nonlethal injuries. Some of these are depressions in the cranial vault (particularly towards the front and the left, presuming mostly right-handed opponents), facial fractures, nasal fractures, traumatic tooth loss, and fractures of the bones of the hand.

Crude limestone group depicting two men wrestling. Traces of red loin cloth on one, and black on the other. Courtesy Petrie Museum.

Spear or javelin throwing has also been attested in antiquity. Although we have evidence of predynastic flint points and dynastic iron spear tips, it’s unclear whether these were used for sport (how far one can throw) or for hunting. Actually, it’s unclear how the two became separate. Hunting was (and continues to be) a major sport – although not one with a clear winner as in racing or wrestling – and the only difference is that in javelin the target isn’t moving (or alive). In the past few years, research has been conducted into the antiquity of spear throwing. One study argues that Neanderthals had asymmetrical upper arm bones – the right was larger due to the muscular activity involved in repeatedly throwing a spear. Another study used electromyography of various activities to reject the spear-thrusting hypothesis, arguing that that the right arm was larger in the specific dimensions more associated with scraping hides. Spear throwing is attested bioarchaeologically in much later periods. A particular pathological pattern called “atlatl elbow”: use of a tool to increase spear velocity caused osteoarthritic degeneration of the elbow, but protected the shoulder.

A final Olympic sport is chariot racing and riding. Horses were probably only domesticated around 5500 years ago in Eurasia, so horse sports are really quite new compared to running and throwing! It’s likely that horses were originally captured and domesticated for meat at least 1000 years before humans realized they could use them for transportation. The Olympic races were 4.5 miles around the track (without saddles or stirrups, as these developments had not yet reached Greece), and the chariot races were 9 miles with either 2 or 4 horses. Bioarchaeologists have noted signs of horseback riding around the ancient world – signs include degenerative changes to the vertebrae and pelvis from bouncing as well as enlargement of the hip socket (acetabulum) and increased contact area between the femur and pelvis from when they rub together. In all cases, more males than females had these changes, indicating that it was more common for men to ride horses.

Of course, there are many more sports that existed in the ancient world – other fighting games including gladiatorial combat, ritualized warfare, and games with balls and sticks (including the Mayan basketball-esque game purportedly played with human skulls). Often games were dedicated to gods, or resulted in the death of the loser(s). However, many of these, explored bioarchaeologically, would result in similar musculoskeletal changes and injury patterns discussed above. Many games have probably been lost to history. Considering the vast span of human activity, it’s likely sports of some kind have always existed, from the earliest foot races to the modern Olympic spectacle.

Sources

Bramble, D.M. and Lieberman, D.E. 2004. Endurance running and the evolution of Homo. Nature 432(7015), pp. 345–352.

Carroll, S.C. 1988. Wrestling in Ancient Nubia. Journal of sport history 15(2), pp. 121–137. Available at:

Larsen, C.S. 2015. Bioarchaeology: Interpreting Behavior from the Human Skeleton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lieberman, D.E. 2012. Those feet in ancient times. Nature 483, pp. 550–551.

Martin, D.L. and Frayer, D.W. eds. 1997. Troubled Times: Violence and Warfare in the Past. illustrated. Psychology Press.

Perrottet, T. 2004. The Naked Olympics: The True Story of the Ancient Games. Random House Publishing Group.

Close

Close