Jewels of an Ancient Civilization

By Julia R Deathridge, on 1 March 2018

Whenever I’m in the Petrie Museum I’m always drawn to the jewellery. This is because a) much like a magpie my attention is easily attracted to shiny pretty objects, and b) I would actually wear a lot of the pieces on display, probably to some future fancy event that I’ll one day attend post PhD life. So I decided to do a little research on the history of jewellery in ancient Egypt and pick out my favourite pieces from the collection.

Gold wide collar necklace, dynasty 18. From the tomb of the three minor wives of Thutmose III. CC BY-NC 2.0 © Peter Roan

The rise of extravagant jewellery

As far back as the Stone Age, our ancestors have been decorating themselves in jewellery. Originally these were just simple pieces crafted from easily available resources such as seashells, bone and animal skins. However, the ancient Egyptians had other ideas, and they would go on to create trends and styles of jewellery that would live on to this day.

The discovery of gold in ancient Egypt, along with the use of precious gems, resulted in the creation of highly lavish jewellery pieces that epitomised the luxury culture of nobles and royals. As technology advanced and materials became more readily available, the popularity and extravagance of jewellery also increased, making it one of the most desirable trade items of the ancient world.

Jewellery and religion

Jewellery was extremely popular in ancient Egypt. Everyone wore it, whether they were male, female, rich or poor. But jewellery was not just about adorning oneself with pretty gems; it also acted as symbol of status and was steeped in religious beliefs.

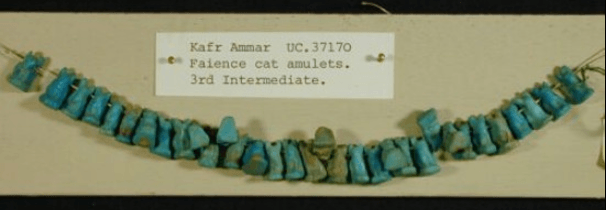

Small charms, known as amulets, were of particular religious importance to ancient Egyptians. They believed that these charms had magical powers of protection and healing, and would bestow good fortune to the wearer. Much like charm bracelets today, these charms were commonly worn as part of a necklace or bracelet, and the shape or symbol of the amulet would specify a particular meaning or power.

Jewellery offered magical powers to the dead as well as the living, and ancient Egyptians were often buried wearing their prized jewels. One of the most common amulets to be buried with was the scarab, as it symbolised rebirth and would ensure reincarnation to the next level.

Materials and metals

The materials that a jewellery piece was made out of acted as an indicator for social class. Nobles would wear jewellery made up of gold and precious gems, and others would wear jewellery made from copper, colourful stones and rocks.

Gold was the most commonly used precious metal, due to its availability in Egypt at the time and its softness, which made it the perfect material for establishing elaborate intricate designs. Moreover, the non-tarnishing properties of gold added to the magical prowess of the metal, leading ancient Egyptians to believe that it was the ‘flesh of the gods’.

Another regularly used material was the semi-precious stone Lapis Lazuli. The deep blue colour of Lapis Lazuli symbolised honour, royalty, wisdom and truth. Other prized stones included obsidian, garnet, rock crystal and carnelian, pearls and emeralds. However, artificial more affordable versions of these precious gems were also crafted, and commonly worn by the lower classes. Much like the fake diamonds and pearls of today, these artificial gemstones were practically indistinguishable from the real thing.

I want that jewellery!

So now we’ve had a little history. Lets get on to the important stuff – which pieces of jewellery I would most like to wear!

First, lets start with the earrings. It wasn’t actually until King Tutankhamen that earrings became a popular jewellery item among ancient Egyptians. The style and use of earrings is likely to have been brought over from western Africa. My favourite earrings are these beautiful hoops, which would not look out of place on stall in a Brick Lane market!

First, lets start with the earrings. It wasn’t actually until King Tutankhamen that earrings became a popular jewellery item among ancient Egyptians. The style and use of earrings is likely to have been brought over from western Africa. My favourite earrings are these beautiful hoops, which would not look out of place on stall in a Brick Lane market!

Another piece that would nicely fit into my jewellery collection is a string of faience cat amulets. Firstly, it will go brilliantly with all my other cat jewellery. Secondly, cats were highly regarded in ancient Egypt and these cat amulets would likely to have been of great importance to the owner.

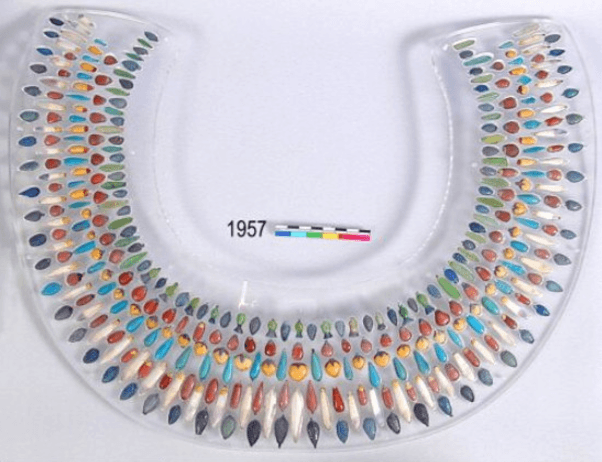

Finally, the ultimate extravagant piece from the collection that I would love to own, is this wide collar necklace, which was likely to have been worn by Akhenaten, Tutankhamen’s father. Each bead was excavated separately and the design of the necklace was reconstructed for the Petrie collection. Additionally, conservation revealed a turquoise bead (11th from the right) to have a cartouche of Tutankhamun. When you’re next in the Petrie, see if you can spot it!

Close

Close