By Kevin Guyan

‘Life Painting’, Slade School of Fine Art. George Konig, Keystone Press Agency.

The idea of Bloomsbury is as much a product of the mind as it is a geographical location. Like Soho, its borders have been established through a mixture of real and fictional ideas, dependent more upon common opinion than municipal rulings. The borders of Bloomsbury have been a common theme discussed by visitors to UCL Art Museum’s ongoing exhibition, Black Bloomsbury.

In my role as a Student Engager, it has been my task to draw links between the exhibition material and my own research interests. My work explores how domestic spaces impacted upon the production and reproduction of masculinities in the postwar period (c. 1945-1966), a topic not unrelated to some of the themes emerging from the exhibition. Afternoons spent engaging in the museum have helped shape my own research; offering a refreshing and reflexive dimension to my work. Discussing people’s opinions on historical ideas has challenged visitors and I to reconsider our views. The process usually begins with a casual, “is this your first time at the exhibition?” After this pleasant introduction and explanation of my role within the museum; around half of the visitors will continue to explore the exhibition on their own, the other half will return with their thoughts, their opinions or questions on the work.

Although my own research focuses upon a different time period (1945-1966 rather than 1918-1948) and a different subject matter (White men rather than Black and Asian men and women), I have located some common themes running across both examples:

Space and identity

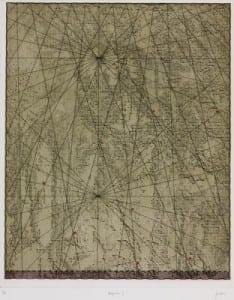

The relationship between space and experience, particularly within the context of identity, is one key example. Black Bloomsbury is co-curated by Dr Caroline Bressey and Dr Gemma Romain, from the Equiano Centre based in UCL’s Geography Department, and because of this geographical context, an effective sense of people and place emerges throughout the exhibition. For example, upon arrival, visitors are met with a large map detailing around 40 locations and a list of characters linked to the exhibition – showing where the characters lived, worked, met and socialised.

The role of place and space links to a secondary project I have been exploring in the past two years, focusing on how bodies were understood within dance hall spaces in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. In my work, the dance hall is framed as more than simply a backdrop for events and instead participates in my historical research as a productive force shaping the actions described. For example, my research has explored the architecture and spatial arrangement of dance halls, admission policies, rules and rituals – all components that impacted a particular sense of identity when ‘going dancing’. It appears to be the case that Bloomsbury had a similar affect upon the characters featured in the exhibition.

Methodology

Equally interesting has been a consideration of the exhibition’s methodological approach. Alongside paintings, photographs are also displayed as a means to show how historians have been able to ‘see into the past’. Unlike text sources that may make no mention of race, photographs present a visual window through which it is often possible to ‘see race’. A key example of this approach in the exhibition is a class photograph of art students based at the Slade in 1938. Although the name and background of every student is not known, the photograph allows modern-day observers to see the racial diversity of those attending the school at that time.

This is something I intend to echo in my own historical writing, in which actions and behaviours of men in domestic spaces are often hidden or beyond the vision of typical research methods. Of course, it is very unlikely for source material to indicate that a household task was conducted in a ‘manly fashion’ or read personal accounts by men of domestic space, in which their sense of gender is discussed. This therefore leads to questions over how best to trace these actions and behaviours? This can be remedied by examining family photograph albums, documentary footage or any other visual source offering uncontrived access to spaces of the past, allowing historians to ‘see’ what men were doing in the home and how they were interacting with their environment.

Importantly, like Black Bloomsbury, my work also intends to not simply describe the actions and behaviours located or analyse them only within the confines of what is being discussed. Instead, there is a need to conduct historical leaps – in which ‘everyday examples’ are used to consider what these performances say about wider ideas of race, gender and nation.

Politics and historical baggage

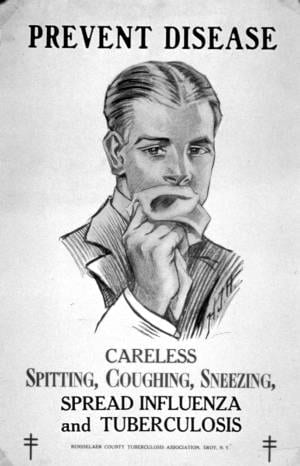

One key focus of the exhibition is on artists and their sitters, based on work developed with the Drawing Over the Colour Line project. The relationship between artists and sitters has evoked several questions among visitors over the identities of these sitters and how they fit into wider social contexts of early 20th Century London. What is often most interesting in the photographs of artists and their sitters is not located in the foreground but what is actually taking place in the background of the images. A particular talking point has been a photograph of a Black male model, sitting perched in a loin cloth in the middle of the room, surrounded by several White, female students. It is difficult not to see this image of a near-nude Black male and young, White women without setting-off historical alarm bells. Yet, due to the spatial context of where these people are situated (in an artist’s studio rather than on the street) certain social customs appear to be excused, creating a situation far removed from the moral panic that may be found elsewhere in 1940s London over the association of Black men, quite often American servicemen, and White women.

Engaging upon ideas that are not resident in the distant past, has the potential for divided opinions and clashes over differing histories. In my own public engagement events on experiences of ‘going dancing’ in London in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, there was often a tension between ‘official histories’ and personal reminiscences. How can a workable history be extracted from memories – whose memories should matter most? Should historians try to be as objective as possible or acknowledge that the past can be mined to satisfy contemporary political needs and desires? These themes also emerge throughout Black Bloomsbury. Some visitors have questioned the purpose of the exhibition and the political motivation for attempting to expand people’s image of Bloomsbury. As I see it, it is not an attempt to evict Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey and John Maynard Keynes from their associations with Bloomsbury and replace them with a new assortment of characters but instead to complicate this image and suggest that, as was the case with areas like Soho, there was an equally cosmopolitan presence in early 20th Century Bloomsbury. Through the production of historical geographies or geographical histories, the exhibition and people’s responses to the material continues to show the importance of space in shaping the actions of historical actors and how historical figures are perceived by those living in the present.

***

Kevin Guyan will be leading a walking tour of Black Bloomsbury between 12 and 1.30pm on Saturday 26 October, exploring topics including geographical settlement, student organisations such as the Indian Students Union, Black visitors to the British Museum’s Reading Room and the fight against the ‘colour bar’ in the area.

He will also give a talk titled Going Dancing: Black Bloomsbury and Dance in the 1940s about the Black presence in 1940s Bloomsbury, focusing on histories of cultural interaction in social spaces such as dancehalls. The event takes place at UCL Art Museum on 15 November between 2 and 3.30pm.

For further information on either event please contact Martine Roulea, UCL Art Museum, m.rouleau@ucl.ac.uk or 020 7679 2540.

Close

Close