Question of the Week: When did the tradition for Grave Goods stop?

By Lisa, on 15 October 2014

Last week I had an interesting discussion with a visitor to the Petrie museum about grave goods.

The shelves of the museum’s cases are lined with an impressive quantity of grave goods, representing a date range that covers most phases of Egyptian history. And this is hardly surprising. Of the 52 excavation locations detailed in a breakdown of Petrie’s field seasons between 1880 and 1938, over half (26) are cemeteries [1].

The finds brought back to UCL by Flinders Petrie after these excavations comprise a diverse assemblage of items. Like those observed in contemporary cultures elsewhere, the grave goods in the early stages of Ancient Egypt consisted of a mixture of every day objects, food items and those more unique or personal accessories, including combs, jewellery and trinkets.

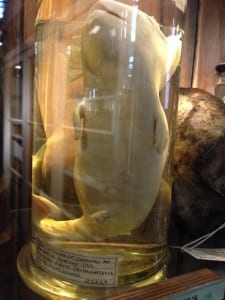

By the Middle Kingdom, however, small figures starting appearing in tombs – early versions of what came to be known as Shabti – meaning ‘answerer’ – figures. By the end of the Middle Kingdom, shabtis were an established funerary tradition and thereafter became prevalent amongst groups of grave goods in one form or another for the remainder of Ancient Egypt’s history. Petrie’s collection contains (at least, according to the electronic catalogue) 1,841 shabtis.

Most commonly shown mummified, the shabti figures act as servants for the deceased in the afterlife – bringing them food or undertaking labour on their behalf, often as instructed in the inscription from the Book of the Dead with which they are decorated [2]. Because of this, they are regularly depicted holding hoes and with baskets on their back for collecting the farmed food for the deceased: see UC39708, a black steatite shabti from the 18th dynasty (c. 1500-1298 BC) and UC39765, a pottery shabti from the 19th (c. 1298 – 1187 BC).

The popularity of shabtis continued on throughout the New Kingdom, when they were increasingly being manufactured in faience: something explored by artist and archaeologist Zahed Taj-Eddin in the current exhibition ‘Nu’ Shabtis Liberation, in which 80 modern shabtis have escaped their enslavement to pursue their own hobbies amongst the Petrie’s cases [2].

So the visitor and I had plenty to talk about.

Then she asked me ‘When did grave goods stop?’

Her husband promptly answered ‘When Christianity was introduced’, but in fact this answer is not quite so straightforward. Firstly, there is no neat way of prescribing a date to the introduction of Christianity, and secondly, contemporary studies would shy away from using burial practice, especially solely grave goods, as a direct reflection of culture.

In Egypt, Christianity first appeared during the Roman rule – which was established after Mark Antony and Queen Cleopatra VII were defeated by the future emperor Augustus in 30 BC (leaving Egypt annexed to Rome as the wealthiest province in its empire) – but it was not adopted seamlessly.

In Egypt, Christianity first appeared during the Roman rule – which was established after Mark Antony and Queen Cleopatra VII were defeated by the future emperor Augustus in 30 BC (leaving Egypt annexed to Rome as the wealthiest province in its empire) – but it was not adopted seamlessly.

The conquering Romans had left Egyptian religion well alone, indeed had many even incorporated its traditions into their own belief systems, with several Roman emperors completing Egyptian temples during their tenure. Consequently when St Mark the Evangelist purportedly chose to establish the Church of Alexandria – one of the original three main episcopal sees of Christianity – around 33-43 AD, it was not to a people who welcomed it with open arms. Christians were persecuted for their faith until 313 when Constantine I issued the Edict of Milan to prevent their mistreatment within the Roman empire – but hereafter, worship of Egyptian deities still continued: archaeological evidence in the form of graffiti at the Temple of Isis at Philae shows that worship continued there into the 6th century.

In England, recent work from Prof. Christopher Scull points towards a cessation of grave goods in the Anglo-Saxon culture shortly before the end of the 7th century, but again – this is not necessarily a hard-and-fast indication that thereafter these burials were all Christian, instead this might have been a response to broader cultural or economic influences [4]. Current approaches warn strongly that there is in fact no evidence to support prescriptive definitions of either Christian or pagan burials during the Early Medieval period. Indeed by the 11th century, grave goods were commonly included in Christian internments as a way of marking out members of the religious community [5].

And so the ‘Question of the Week’ goes almost unanswered – but does give some good food for thought on our approaches to burial practice and material culture.

Lastly, the subject of grave goods is an interesting one in the context of my own research. Until the change in legislation in 1997, grave goods were not classified as Treasure as they did not display animus revertendi, the phrase used to describe an ‘intent to return’ on the part of whoever had buried the treasure in the first place. Unlike a hoard which is buried with the intention of retrieving, grave goods are donated to the dead and intended to be left intact in the grave – so consequently were not protected as Treasure Trove before the law was updated.

As such the incredible grave goods from Sutton Hoo, that nationally recognisable Anglo Saxon ship burial, were only saved for the public benefit through the benevolence of the landowner Mrs Pretty, who would have been quite within her legal rights to see the artefacts piece by piece should she have wished to. (For more on the Treasure definition, see my previous blog here [6])

‘Nu’ Shabtis Liberation is on at the Petrie Museum until 18 October.

[1] http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/petriedigsindex.html

[2] http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/articles/e/egyptian_shabti_figures.aspx

[3] http://events.ucl.ac.uk/event/event:k36-i0gmqt30-fs2rn/nushabtis-liberation

[4] A. Bayliss, J. Hines, K Høilund Nielsen, G. McCormac and C. Scull (2013) Anglo-Saxon graves and grave goods of the sixth and seventh centuries AD: a chronological framework. Leeds, Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 33

[5] Gilchrist, R. (2005) Requiem for a Lost Age British Archaeology 84 http://www.archaeologyuk.org/ba/ba84/feat2.shtml

[6] https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/researchers-in-museums/2013/01/14/the-staffordshire-hoard-defining-treasure/

Close

Close

![King George VI, Queen Elizabeth and an assortment of postwar planners at the County of London Plan exhibit. University of Liverpool archive [D113/3/3/40].](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/researchers-in-museums/files/2014/08/County-of-London-Plan-Blog-e1409243452716.jpg)