Cerys Bradley: My Last Blog Post

By uctzcbr, on 14 June 2019

In April, I had my last shift at the UCL Art Museum . Last week I had my last shift in the Petrie Museum, next week will be my last shift ever at the Grant Museum. After nearly four and a half years, I’ve finally finished studying at UCL – I passed my PhD viva yesterday and am a few minor edits away from graduation. As working as a student engager has been one of the best things about studying at UCL, I wanted to use this blog post to talk about some of my favourite moments on the job and the things I have learned because of this programme.

Let’s start with my favourite engagements. It was difficult to narrow down the list but I have chosen three, one from each museum. Before I tell you them, I would like to award a “highly commended” prize to the time I spent twenty minutes talking to two visitors in the Grant about how dead baby pigs are used in research in my department before finding out they were vegan. You can read more about the encounter here.

When I started working in the UCL Art Museum, I was incredibly apprehensive – I know nothing about art. My background is in mathematics and the staff in the museum kindly spent a lot of time searching through their catalogue to find related pieces I could talk about (to no avail). So I learned a few facts about Flaxman, the man whose works began the collection, and started offering to take visitors to the Flaxman gallery and the Housman room (a room that hosts several of UCL’s best pieces that should be on public display but are now hidden behind a key-card access only door).

On one of my shifts, a mother and daughter came to the museum. They had just moved to Reading from Pakistan and the daughter wasn’t getting on too well at school. She loved art class so her mum had brought her to London for the day to tour some art galleries. They were a little underwhelmed by our small print room (there wasn’t an exhibition on at the time) so I took them to the Flaxman gallery which displays casts and prototypes of some of the funerary monuments that Flaxman designed and sculpted. Flaxman worked during the British occupation of India and incorporated Indian burial iconography in his work. I learned this from the visitors who explained to me what the specific positions of the figures in the casts and their clothing signified about their lives. The visitors were excited to connect with the work and I learned a lot from them; it was an interaction which really demonstrated how positive the engagement programme could be.

It is at the Grant Museum that I discovered the incredibleness of bats. Once again, I had to work hard with the staff at the museum to identify a way of connecting my research background with the collection. I started talking about the bats because a student in my department did her Master’s project about them. She is an environmental crime researcher (that encompasses both crimes committed against the environment and crimes committed by animals) and used her Master’s dissertation to investigate the destruction of bat habitats in the UK.When on shift, I would hover by the bat specimens and use them to talk about my colleague’s research and, then, how we study crime in our department more generally. When I wasn’t talking to visitors I would idly google interesting facts about bats. They are now my favourite animals – I have two bat tattoos and a bat detector so I can determine the species of bats on Hampstead Heath.

One of my favourite facts to share with visitors is how much bats eat. Insectivore bats can eat up to 7 times their own body weight in insects in one night and fruit bats can eat up to twice their own body weight. I often tell this fact to children and ask them if they can imagine eating twice their own body weight in their favourite fruit. On one occasion, I asked a small boy (whose favourite food was cherries) how much fruit that would be. He asked his mum how much he weighed and then carefully counted two times 22 kg on his fingers before answering, very sincerely, 44 kg. His parents were extremely proud.

This is my favourite bat in the Grant Museum, I think he looks like a mob boss doing a really big laugh

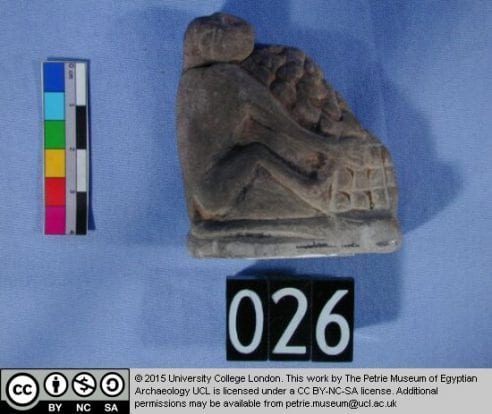

When I work in the Petrie Museum, I talk about two things: the pot burial and Amelia Edwards. Three if you count helping children find the pink pyramids hidden in the displays. I like talking about the pot burial because we know so little about it and it’s a brilliant object for explaining to children the mechanics and limitations of archaeology.

When children approach the object, I ask them if they were an archaeologist and they found a skeleton in a pot, what questions would they try to answer. They nearly always ask the same three questions: “who was this person?”, “how did they die?”, and “why are they in a pot?”. Then we try to answer the questions together. On one occasion a tiny child looked me dead in the eye and declared that the person had died when they were hit on the head and all their blood had run out down their face (this was acted out for emphasis). The small child then went and did some colouring and I have had nightmares ever since (not really).

Every instance of talking to a child about the pot burial becomes a favourite engagement at the Petrie. I enjoy observing their curiosity and creativity. It is even more fun when they come to terms with the idea that we just don’t know the complete answer to some questions and so they get to make up their own stories.

I have worked three Saturdays a month nearly every month for the past three years and experienced hundreds of engagements with visitors of UCL’s museums. I have learned a lot about their lives and about the collections, I have grown more confident talking to strangers, I have gotten better at explaining scientific concepts and I have discovered a thousand ways to say, “I have absolutely no idea, let’s google it”.

This is my final blogpost, which is why it is long and overtly sentimental, but I wanted to sign off by saying thank you to the UCL Student Engager’s programme for the huge, positive impact it has had on my time here at UCL.

Close

Close