by Lisa Plotkin

by Lisa Plotkin

Recently I had the opportunity to sit down with young artist Siân Landau to discuss her work, and in particular, her contribution to UCL Art Museum’s Duet exhibition. For such a young person Siân’s CV is impressive. A recent graduate of the Slade School of Fine Art, she is also the recipient of the prestigious Thomas Scholarship from the Slade and has also served as a Heal’s artist in residence.

Duet is the fifth annual collaboration between the Slade School of Fine Art and the UCL Art Museum. The exhibition challenged Slade students to take inspiration from a piece of work already in the Art Museum’s vast collection, and produce something in response. The results were as varied as they were thought provoking, with participating artists taking inspiration from Hogarth to Gwen John, and many others. But it was the four watercolours on the wall, two of which are shown below, depicting colourful female nudes that really caught my eye.

Entitled Slade Ladies Do It Better this piece by Landau sheds a unique light on the Slade as a historical institution for female artists and allows us to re-imagine the ways in which the female nude has become an artistic and cultural symbol. Landau’s accompanying text explaining the piece in more detail reads as follows:

The four watercolours I have made are of nude women who are currently studying at the Slade, in each image a woman recreates the poses of female life models from drawings made by some of the first women to study there. The studies I work from were made between 1893 and 1915. I acknowledge the original works by naming each piece with the first name of the artist who made the drawing; Alice, Dorothy, Ethel and Eveleen. My contemporary response to these traditional life drawings celebrates the diversity of female beauty, with colour and decoration to bring life and delicacy. I hope to encourage reflection in a society where women continue to feel the pressures of the male gaze and its unrealistic ideals.

As an historian of women and gender, I immediately wanted to sit down with Sian and try to get at what compelled her to make this piece, find out more about her process, ask what kind of reaction her work is garnering, and find out what is in store for her next.

Q: How did you become a student at the Slade and what has inspired you to continue making art?

A: I have always loved art and when I was at school doing my A levels I thought to myself wow, I can actually go forward with this and really enjoy studying it! So then I did a foundation course at Chelsea [College of Art and Design] in 2009-2010 and I absolutely loved it. It was a real chance to just explore so many different ways of making art- we did fashion, we did graphic, fine art, visual communications and media, and it was then that I knew fine art was definitely for me. I applied to the Slade from there and the last three years here have been amazing. They give you the freedom to do what you want to do and it has only been in the last year that my interests have taken on their true identity, I guess. The first couple of years you are kind of dabbling around, thinking what is it- what is the crux of my work? It takes some time to figure that out.

Q: What was it like working within the constraints of Duet as a concept? What did your process entail?

A: Artists are always inspired by a number of things, but it was different to actually come in and work with a specific piece. But, it was within my own art practice that I started looking at women artists and the place of erotica in feminist discourse. That tension isn’t resolved yet, but I knew I was interested in exploring it further, so when this project came up I thought I would just go in and see what they had, like what I might respond to. And when we came in for the initial briefing they had loads of easels out around the room with loads of different works that they had selected and one of them was a nude woman- you know, a life model- and I saw it and I thought that’s what I’ve got to respond to!

I mean in a contemporary sense a nude woman is not a shocking thing anymore, it’s everywhere so I just thought I could make a piece that commented on that ubiquity. And then it was through coming back and doing research and looking at more women artists that drew women at the Slade that I really made the connection with how I could take that and do something with it. And for me it just seemed really important and obvious that I should take that and literally use the women working now at the Slade because life drawings aren’t really done here anymore- I mean it’s not a big part of the programme – so with this piece I was able to bring that back again as well.

Q: What do you hope to convey with this piece?

A: I hope to highlight the history of the Slade as an educational facility for women, which was something that I found out more about in the process of making this piece. The Slade opened in the 1870s and women were admitted, which was 25 years before any other professional art school let women enroll, which was an amazing fact to find out. What a great thing for women’s rights to be able to study at that level and I wanted to increase awareness of that.

Q: How does this piece fit in with the rest of your work? Do you explore these types of themes often?

A: Well it’s in there. The degree show I just exhibited was more about desire- the physicality of desire. I was making paintings that were quite abstract at first, but then when you look closer you see that there is actually a really fluid image of two people in a sexual act. And they were all quite colourful- I love to experiment with colour and pattern and line as well. My drawings are usually a lot looser than is shown with this piece. And my ceramic sculpture pieces deal with the hands on side of sexual encounters and just handling something, whether it’s the body, or for me it was handling clay, in order to express desire. So, yes my previous work does link in with some of the themes I explored in this piece, so it was nice to run something parallel with my contemporary practice, yet still different. In the future I do want to look more into the history of the nude, which does have an immense history.

Q: And how has this piece been received?

A: Overall it has been really positive.

Q: So, now that you have finished at the Slade, what’s next for you?

A: Good question! I am not going on to an MA & further study is not a priority for me at the moment, but I will be making work, doing some research, just getting a studio space and carrying on making work.

Filed under Lisa Plotkin, UCL Collections, UCL Exhibitions

Tags: Art Museum, contemporary art, Duet exhibition, fine art, Siân Landau, Slade School of Fine Art, the body in art, the nude, watercolours, women artists

1 Comment »

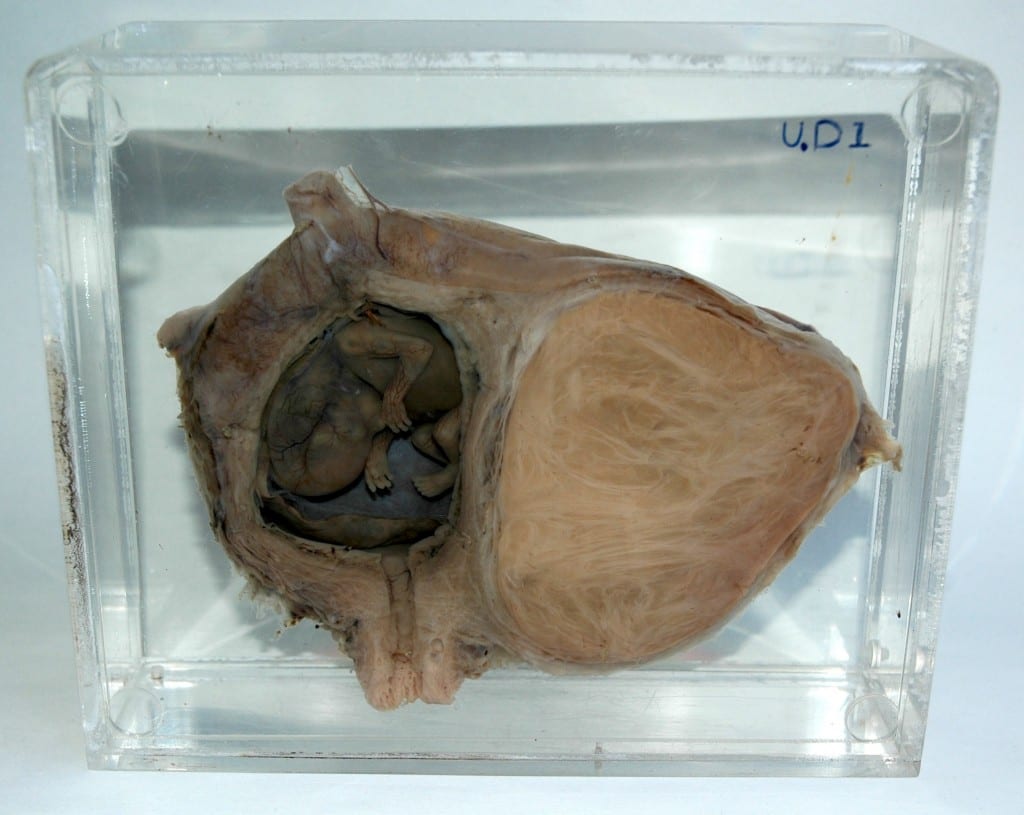

Last Saturday I was engaging at the Grant Museum of Zoology where I started talking with two visitors about the history of science. As a Victorian historian, my doctoral research specifically looks at the historyof Victorian medicine and its relationship to women and the articulation of the healthy female body. There couldn’t be a better setting to discuss those themes than the Grant Museum- the only remaining zoological university collection in London, which houses a dizzying array of zoological specimens dating back to the early nineteenth-century. The museum’s founder, Robert Edmond Grant, is particularly known for his influence on the young Charles Darwin, when the latter studied under him at Edinburgh University.

Last Saturday I was engaging at the Grant Museum of Zoology where I started talking with two visitors about the history of science. As a Victorian historian, my doctoral research specifically looks at the historyof Victorian medicine and its relationship to women and the articulation of the healthy female body. There couldn’t be a better setting to discuss those themes than the Grant Museum- the only remaining zoological university collection in London, which houses a dizzying array of zoological specimens dating back to the early nineteenth-century. The museum’s founder, Robert Edmond Grant, is particularly known for his influence on the young Charles Darwin, when the latter studied under him at Edinburgh University.

Close

Close