Sword Swallowing & Surgical Performance

By Gemma Angel, on 11 March 2013

by Sarah Chaney

by Sarah Chaney

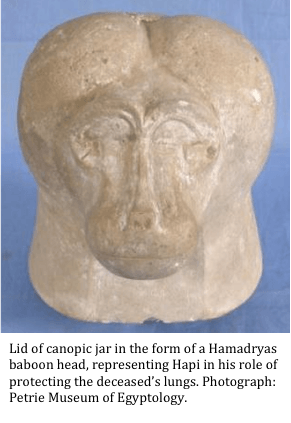

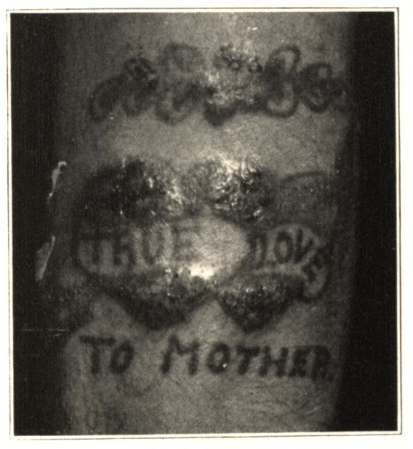

We know sadly little about the sword swallower’s sword that resides in the UCL Pathology Collection: not even how long it has been here. What we do know is that this performer was very unlucky. Perhaps he (or, indeed, she) didn’t tilt his head back far enough. Perhaps he moved during the process of insertion. Whatever the case, the sword pierced the flexible tube of the oesophagus, leading to the performer’s death. The heart and oesophagus were preserved – perhaps as a warning of the dangers of such feats – alongside the weapon that led to his demise.

Fatally ruptured oesophagus, caused by the sword swallower’s sword. Photograph Gemma Angel, UCL Pathology Collections.

Sword swallowing seemingly originated in India some 4,000 years ago, but reached the western world of Ancient Greece and Rome in the first century AD. The performer tilts his or her head back, extending the neck, and learning to relax muscles that usually move involuntarily. A rigid weapon can then be passed down as far as the stomach, usually for just a few seconds, before removal. It is dangerous, certainly, but few performers suffer the fate of the individual preserved in the UCL collections. According to one recent article in the British Medical Journal, most serious incidents occur owing to distraction or attempts at exceedingly complex feats:

For example, one swallower lacerated his pharynx when trying to swallow a curved sabre, a second lacerated his oesophagus and developed pleurisy after being distracted by a misbehaving macaw on his shoulder, and a belly dancer suffered a major haemorrhage when a bystander pushed dollar bills into her belt causing three blades in her oesophagus to scissor. [1]

In many ways, sword swallowing is the opposite of the ingestion of other foreign bodies: rather than swallowing, the performer maintains absolute control over the process of consumption, taming the body’s reflexes and realigning the organs. As Mary Cappello notes in her fascinating literary biography of surgeon Chevalier Jackson (1865 – 1968), who was an expert in foreign body removal, sword swallowing was recognised by doctors as inspirational to their own techniques. Jackson took his lead from German professors Alfred Kirstein and Gustav Killian, who lectured that sword swallowing proved the possibility of passing a rigid tube into the oesophagus, in order to remove lodged objects. Jackson, who developed his own oesophagoscope in 1890, admitted that the abilities of circus performers had opened his eyes to the opportunity of removing foreign objects without dangerous surgery. He even taught his children how to “scope” themselves.[2]

In an intriguing parallel, the insertion of some foreign objects into the human body thus assisted with the removal of others. At the turn of the 20th century, the removal of foreign bodies lodged in the throat and airways frequently required an incision to be made into the trachea or oesophagus, an operation which could prove fatal. In the records of the Royal London Hospital, from 1890 to 1910, we find no mention of oesophagoscopy or bronchoscopy: instead, surgery or the probang or “coin-catcher” was the norm. This latter instrument was generally a simple hook, inserted without any kind of viewing device or illumination. The practitioner would feel blindly for the object, and either attempt to hook it out, or push it into the stomach. This might lead to numerous complications. In 1903, surgeons at the Royal London attempted to remove a halfpenny from the throat of a five-year-old boy by pushing it into the stomach. However, it was subsequently reported that the coin catcher broke off in the boy’s throat, necessitating a major operation from which the child did not survive.[3] Small wonder that, less than a decade later, Jackson declared such objects “rough, unjustifiable, brutal”.[4]

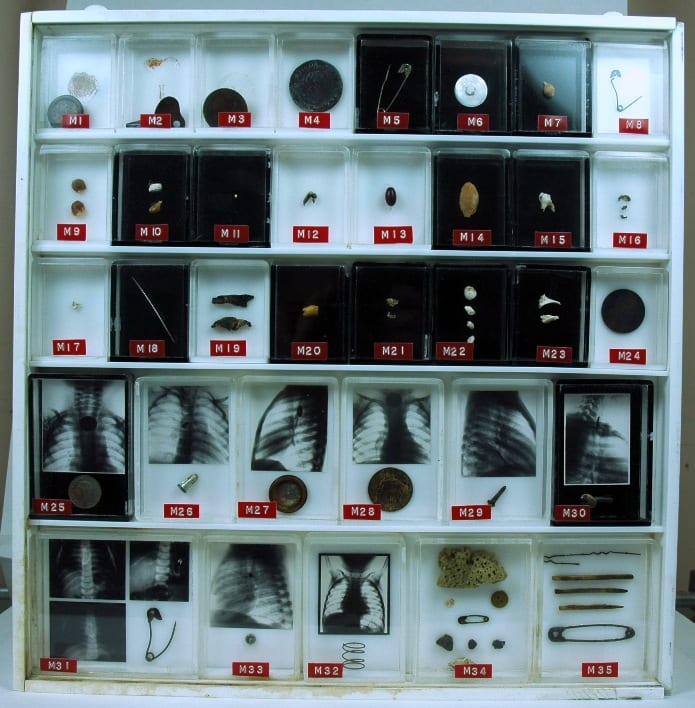

UCL Pathology Collections contains many examples of foreign objects removed from the

human body: this purpose built display showcases many such objects, some with

small x-rays of the objects prior to removal.

X-ray imaging techniques aided the removal of foreign objects by instruments, and foreign body specimens are often accompanied by photographs showing the item’s location in the human body. The above set of items is found in the UCL Pathology Collection, the objects having been gathered by several surgeons in the 1920s – ‘50s. At some point, the individual boxes made for each specimen were mounted together, in a specially designed plastic surround. Fittings on the back indicate that the case was made to hang on a wall. But why? To decorate the office of a surgeon, showing off his achievements? To offer a warning to others to take care (particularly parents, for all these objects were removed from children and infants)?

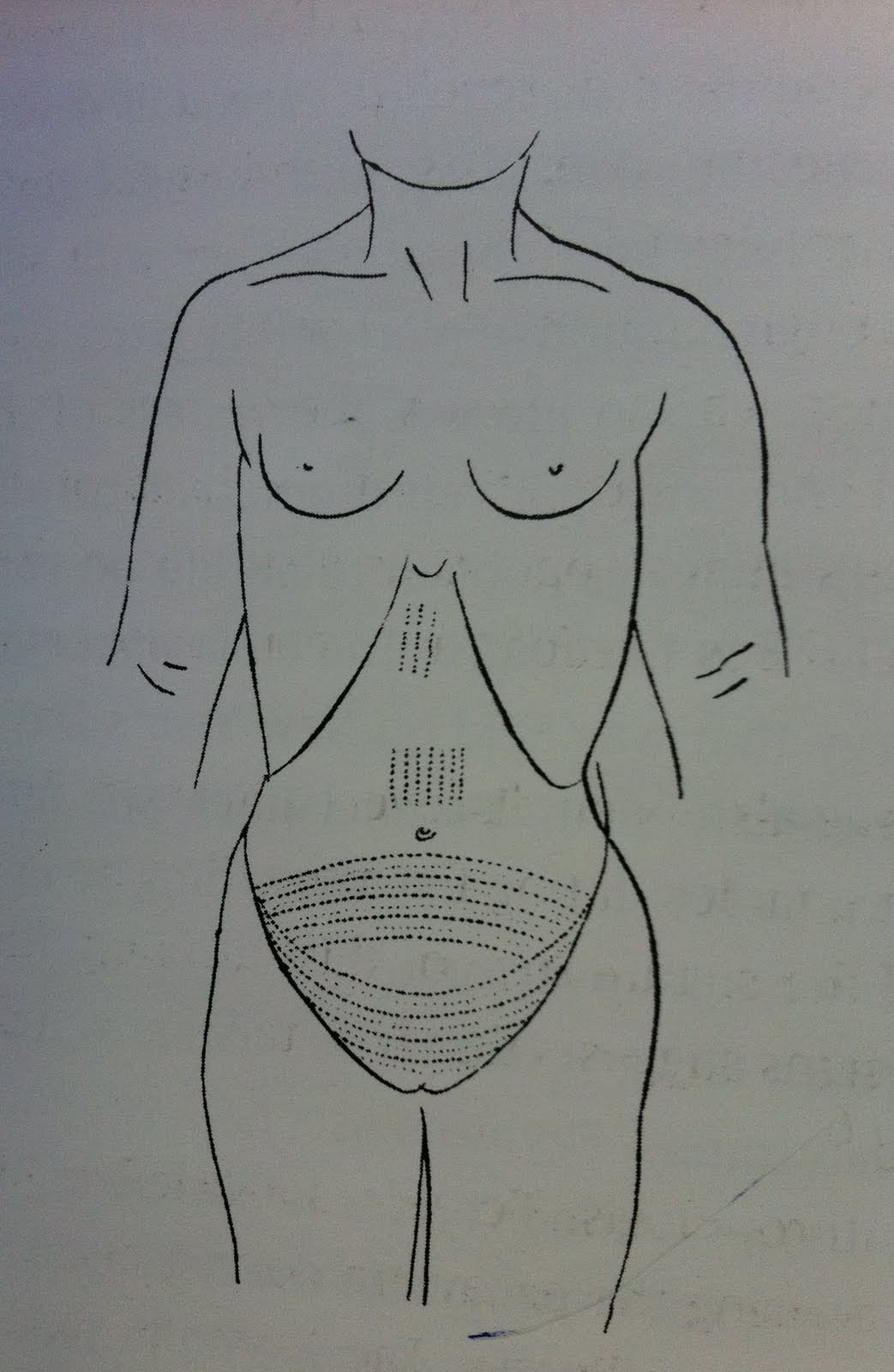

Chevalier Jackson claimed that his collection of more than two thousand foreign bodies (now housed in Philadelphia’s Mutter Museum) was not a curiosity, but indicative of the everyday nature of foreign body ingestion and inspiration. Yet many of these specimens are not everyday. The two boxes of multiple objects in the bottom right, for example, were removed from the vaginas of young girls (six and eight years old respectively). The case notes do not indicate how these objects arrived in their location. Did the girls insert them themselves, or might it be a sign of sexual abuse? In her research into the medical histories of Jewish immigrants to the East End of London in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Carole Reeves came across a case of multiple foreign body insertion in a young woman, whose vagina was found to be tightly packed with pins. Reeves speculated that Leah G. might have inserted these items in an effort to ward off potential (and actual) abusers.[5]

In most instances, we can uncover little about the motivations of those in the late 19th and early 20th centuries whose foreign bodies are recorded in medical records: surgeons were often little interested in how the object came to be in its current location, but only in its removal. Yet this may often make such displays still more intriguing than otherwise. As Mary Cappello put it, in a video discussion of the UCL artefact pictured above for the Damaging the Body website: “What is the border or boundary between human flesh, between human life and the object world?”

References:

[1] Brian Witcombe and Dan Meyer, “Sword Swallowing and its Side Effects”, in British Medical Journal, 333 (2006), 1285-7, p. 1287.

[2] Mary Cappello, Swallow: Foreign Bodies, Their Ingestion, Inspiration and the Curious Doctor who Extracted Them, New York, London: The New Press (2011). Website: http://www.swallowthebook.com/

[3] Royal London Hospital Archives, Surgical Index 1903, LH/M/2/9, patient no. 4086.

[4] Chevalier Jackson, Lecture to the Kings County Medical Society, December 19 1911, quoted in Cappello, p. 208.

[5] Carole Anne Reeves, Insanity and Nervous Diseases Amongst Jewish Immigrants to the East End of London, 1880 – 1920 (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of London, 2001), p. 213.

Close

Close