I spy with my little eye… Micrarium Top 5

By tcrnkl0, on 9 January 2018

Want a tour through the Grant Museum’s iconic display of the tiny creatures that populate our world? Well unfortunately, it’s much too small for that! However, here I’ll tell you about five of my favourite slides to be on the lookout for when you visit.

The Micrarium’s floor-to-ceiling lightboxes illuminate 2323 microscope slides featuring insects, sea creatures, and more, with another 252 lantern slides underneath. While this sounds like a lot of slides, it’s only around 10% of what the museum holds. Natural history museums often find it difficult to display their slide collections, but the diminutive creatures often featured on them make up most of our planet’s biodiversity.

I start most of my conversations with visitors during Student Engager shifts here – the Micrarium provides a clear illustration of my PhD research about how challenging aspects of diversity (of all kinds) are integrated into existing collections. It’s also an ideal place within the museum to try to pause people in the flow of their visit – it’s hard to resist stopping to snap a selfie or two.

The soft glow of the Micrarium’s backlit walls often draws people into the space without realising the enormity (or tininess!) of what they’re looking at. Over time, I’ve cultivated a number of favourites that I point out in order to share the variety, strangeness, and poetry of the individual slides.

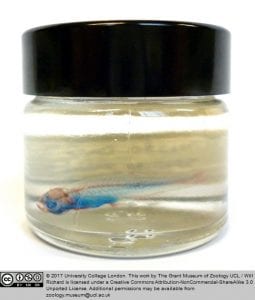

Small and mighty

I was attracted to this slide because at first I thought it looked like a little flying squirrel. In actuality, it’s the larvae of a mantis shrimp.

The mantis shrimp is an incredible animal. To start, they have the most complex eyes of any animal, seeing a spectrum of colour ten times richer than our own. Its two ‘raptorial’ appendages can strike prey with an amount of force and speed, causing the water around them to boil and producing shockwaves and light that stun, smash and generally decimate their prey.

For more, check out this comic by The Oatmeal that illustrates just how impressive mantis shrimp are.

‘and toe of frog, wool of bat, and tongue of dog’

This is one of my favourite labels in the collection – was a zoologist also dabbling in witchcraft ingredients? Probably not. But, I’d love to know what the slide was originally used for.

The slide itself also looks unusual due to its decorative paper wrapping. These wrappings were common to slides from the mid-19th century, which were produced and sold by slide preparers for others to study.

Many of the slides in the Micrarium were for teaching students who could check out slides like library books. So, perhaps it illustrated some general principles about beetle eyes rather than being used for specialist research.

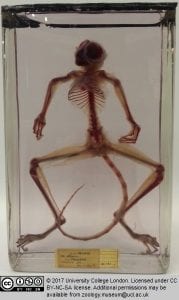

Cat and Mouse

One of the secrets of the Micrarium is that there are bits of larger animals hidden among all of the tiny ones. I like how the mice look surprisingly cheerful, all things considered. Bonus: see if you can also find the fetal cat paws!

Seeing stars

This is a young brittle star, which in the largest species can have arms extending out to 60cm. Brittle stars are a distinct group from starfish; most tend to live in much deeper depths than starfish venture. They also move much faster than starfish, and their scientific name ‘Ophiuroidea’, refers to the slithery, snake-like way their arms move.

This slide can be found at child height, and it’s nice to show kids something they’re likely to recognise.

And finally:

Have you seen the bees’ tongue?

Showing visitors this slide of the bee’s tongue almost always elicits surprise and fascination. Surprise at the seemingly strange choice to look at just the tongue of something so small and fascination at how complex it is.

We don’t normally think of insects having something so animal-sounding as a tongue (more like stabby spear bits to sting or bite us with!). But, bee tongues are sensitive and impressive tools: scientists have observed bee tongues rapidly evolving alongside climate change.

Good luck finding these…or your own Top 5! Share any of your favourites in the comments.

The Grant Museum blog did a similar post five years ago when the Micrarium opened. These don’t overalp with my Top 5 (which is easy to avoid when there are 2323 slides), so you should also check that out.

Close

Close