Guest post by Louise Mc Grath-Lone, Research Fellow (UCL Institute of Health Informatics), Rachel Pearson, Research Assistant (UCL Institute of Child Health) and Ania Zylbersztejn, Research Fellow (UCL Institute of Child Health)

In July 2021, we held a session on code sharing as part of the UCL Festival of Code and were thrilled to have almost 90 attendees from 9 out of UCL’s 11 faculties – highlighting that researchers from across a wide range of disciplines are interested in sharing their code.

The aims of the session were to highlight the benefits of code sharing, to explore some of the barriers to code sharing that Early Carly Researchers may experience, and to offer some practical advice about establishing, maintaining and contributing to a code repository.

In this blog, we summarise the benefits and barriers to code sharing we discussed in the session taking into account the views that participants shared.

What is code sharing and what are the benefits?

Code sharing covers a range of activities, including sharing code privately (e.g., with your colleagues as part of internal code review) or publicly (e.g., as part of a journal article submission).

For Early Career Researchers in academia, there are many benefits to sharing code including:

Reducing duplication of effort: For activities such as data cleaning and preparation, code sharing is an important method of reducing duplication of effort among the research community.

Capturing the work you put into data management: The processes of managing large datasets are time-consuming, but this effort is often not apparent in traditional research outputs (such as journal articles). Sharing code is one way of demonstrating the work that goes into data management activities.

Improving the transparency and reproducibility of your work: Code sharing allows others to understand, validate and extend what you did in your research.

Enabling the continuity of your work: Many researchers spend the early years of their career on fixed-term contracts. Code sharing is a way to enable the continuity of your work after you’ve moved on by allowing others to build on it. This increases the chances of it reaching the publication stage and your efforts and inputs being recognised in the form of a journal article.

Building your reputation and networks: Code sharing is a way to build your reputation and grow your networks which can lead to opportunities for collaboration.

Providing opportunities for teaching and learning: By sharing code and by looking at code that others have shared, Early Career Researchers have opportunities to both teach and learn.

Demonstrating a commitment to Open Science principles: Code sharing is increasingly valued by research funders (e.g. the Wellcome Trust) and is a tangible way to show your commitment to Open Science principles which are part of UCL’s Academic Framework and important for career progression.

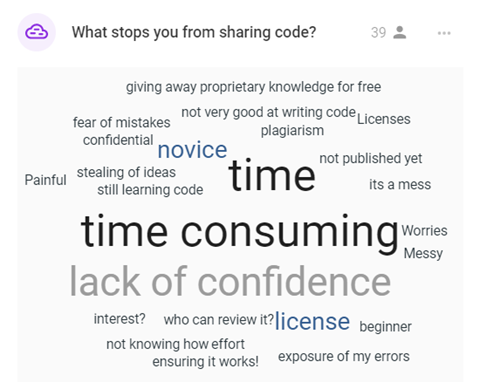

Despite the clear benefits to code sharing, at the start of our session just 1 in 4 participants (26%) said that they often or always share code. However, by the end of the session, almost all participants (90%) said that they definitely or probably will share their code in the future.

What are the barriers to code sharing as an Early Career Researcher and how we can overcome them?

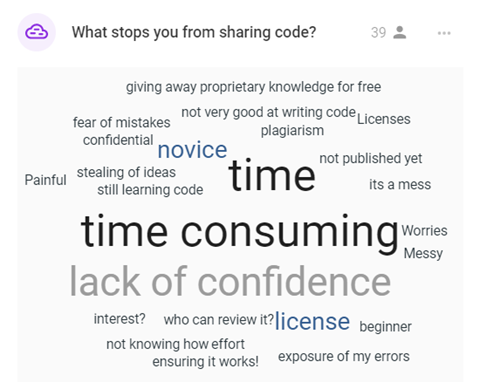

We asked participants what has put them off sharing their code in the past. The most common responses were:

The time and effort required: Ideally, you would write perfectly formatted and commented code on the first go – however, in reality, it often does not work out like this. As you update code and encounter bugs, code can often become messy and considerable time/effort needed to get it to point it can be understood by someone outside the research project. We discussed the importance shifting your perception of ‘shareable’ code. Sharing any code, even if messy, is far more helpful than sharing nothing at all.

Lack of confidence and concerns about criticism: Many researchers who write code as part of their work have very little (or no!) formal training. This means that sharing code can be daunting. For example, researchers may be worried about others finding errors in their code; however, sharing code can help to catch bugs in code early on and can bolster your confidence and reassure you that your code is correct. In the session, we also discussed how getting involved with online coding communities that emphasize inclusivity and support (e.g., R Ladies, Tidy Tuesday or one of the UCL Coding Clubs) can help grow confidence and provide a kinder environment in which to share code publicly.

Not knowing how to share or who to share with: A lack of formal training means that many researchers are unsure about where or how to share code, including not knowing which license to use to enable appropriate reuse of code. We discussed the need for more training opportunities, encouraged setting up your own code review groups (like a journal club, but for sharing and discussing code).

Worry that code will be reused without permission: Some participants were worried about plagiarism and their hard work being re-used without their knowledge or permission. However, hosting your code in a repository like GitHub allows you to choose suitable licence for re-use of your code to prevent undesired use while still supporting open science! You can also see how many people have accessed your code.

How can Early Career Researchers get started with code sharing?

Preparing code to share can take time and, as they work to secure their future within academia, many Early Career Researchers may already feel overloaded and pulled in different directions (e.g., teaching, institutional citizenship, engagement work, producing publications, attending conferences, research management, etc.). However, code sharing is hugely beneficial for a career in academia and so we would encourage all Early Career Researchers to try to find the time to share code by viewing it as an opportunity to invest in your future self. For example, you could:

- Adopt a coding style guide to help produce clear and uniform code with good comments from the outset. This will reduce effort end when you come to share code (and help your future self when you look at your code many years later and have inevitably forgotten what it all does!

- Join a UCL Coding Clubs or online community to learn tips from others about coding and sharing code.

- Learn to use a code repository like GitHub. As part of our session, we delivered an introductory tutorial on how to use GitHub with links to other useful resources (available here).

How can UCL support Early Career Researchers to share code?

We ended the session by asking the participants how UCL could better support them to share their code. Some of the ideas suggested by Early Career Researchers were:

More training on writing and sharing code: For example, one suggestion was that UCL could create a Moodle training course for code sharing. Training about best practice in coding (across several languages) to help Early Career Researchers to write code right the first time would also be helpful.

Simple, accessible guidance about code sharing: This might include checklists or 1-to-1 advice sessions, in particular, to help Early Career Researchers to select the right licenses.

Embed code sharing as best practice at all levels: Encouraging and supporting senior researchers to share code so that it becomes embedded as good practice at all levels would provide a good example for and encourage more junior members of staff. It would also help to ensure that the time and training required to prepare code for sharing is built into grant applications.

Knowledge sharing opportunities: More events and opportunities to discuss how research groups share code to share best practice across faculties throughout UCL.

We would like to thank everyone who attended our session – “Code sharing for Early Career Researchers: the good the bad and the ugly!” – at the UCL Festival of Code for their time and contributions to the lively discussions. All the materials from the session are available here, including an introductory tutorial to getting started with code sharing using GitHub. We would also like to thank the organisers of the UCL Festival of Code for their help and support.

How can Open Science/Open Research support career progression and development? How does the adoption of Open Science/Open Research approaches benefit individuals in the course of their career?

How can Open Science/Open Research support career progression and development? How does the adoption of Open Science/Open Research approaches benefit individuals in the course of their career?

Close

Close